[cross-posted at POT]

No, she didn’t invent pizza. But she was notable in other ways.

Christine de Pizan (born Cristina da Pizzano; 1364-c. 1430 [thus either late mediæval or early Renaissance, depending on your definition]) – poet, historian, essayist, political theorist, political activist, and pioneering feminist – was Venetian by birth; but her father Tommaso, a philosopher and astrologer, had been serving as a temporary advisor at the court of King Charles V of France (a position which he had chosen, in the event perhaps unwisely, over a similar post in Hungary), and when the time came for Tommaso to return to his family in Venice, the king refused to let him leave, and instead insisted that Tommaso bring his family to Paris. Thus Christine grew up in Paris rather than Venice.

Christine de Pizan and the Mutant Head Ladies

As a teenager she was married to Étienne du Castel, a secretary in Charles’s court. Both father and husband encouraged her studies in history, philosophy, politics, literature, and religion – but not, as she would later have cause to regret, in business affairs. In an autobiographical poem, she explains:

My father, whom I’ve aforementioned,

Had one wish in his great ascension:

To have a male child – unfulfilled.

To him he could have safely willed

His mighty fortune and his land.

Between my parents there did stand

A duplicitous agreement,

Or so it seems: my father meant

Something different from my mother,

For instead of male, the other

Sex was I born, though otherwise

I had my father’s looks: his eyes,

His hair, his build. She had tricked him.

But despite the original dictum,

I was a loved and cherished child;

My father’s doubts I had beguiled. …

And thus I grew up without fear

Of the injustice all too near:

Among infant playmates equality

Reigns, whereas adult polity,

Riddled with prejudice, reacts

In the interest of male contracts.

How little I knew, a woman destined

To have, by this menace, lessened

Her fortune, as sole legatee,

Stolen by legal repartee.

Charles V had promised ongoing economic support for Tommaso and his family, but died without having ever officially decreed it, thus leaving the de Pizans suddenly without patronage. (While de Pizan always showers Charles V with praise, both in her autobiography and in her book Deeds and Good Character of King Charles V the Wise, if one reads between the lines one can see that this king was in fact the author of many of her misfortunes – first by compelling her father to bring his family to Paris, and then by not following through with his promises of economic security.)

Then Christine’s father and husband also died, in quick succession, leaving her to be the sole support of both her children and her mother.

Christine’s marriage had been a happy one, and Castel’s death was devastating to her emotionally. Here’s one of the many songs of mourning she wrote in response to his death:

But her widowhood was also a financial and legal disaster. As de Pizan explains in her autobiography:

For I was not with my husband when he was carried off by a sudden plague in the city of Beauvais …. As he was accompanied only by his servants and an unfamiliar retinue, I was not able to get full and precise information on the state of his affairs. For it is customary for married men not to discuss financial matters in detail with their wives, a practice that often leads to great problems, as I have learned from experience, and does not make any sense at all when a woman is not stupid but prudent and wise in her dealings.

Thus it behooved me to set to work, I who had been indulged and pampered as a child and had no experience in such matters, and take the helm of the captainless ship in mid-storm, by which I mean the bereft household far from its homeland. Troubles surged upon me from all sides, and as is the common lot of widows, I became entangled in legal disputes of every sort. …

What a trial it is for a woman like me, who is rather retiring by nature and little concerned with material possessions or money, to be forced by my financial responsibilities to seek out various officials, only to be tormented day after day by their smooth words!

Christine de Pizan’s writings comment frequently on the mutability of fortune.

I’d like to buy a vowel.

Two years earlier she had recounted her life story in a more allegorical form, with the remarkable figure of her transformation into a man:

So moving were my desperate cries

That even before her cold eyes

My plight caused Fortune to amend

Her fiendish ways and be my friend. …

But, fatigued was I from crying;

Near-paralyzed, there lying

I fell asleep toward suppertime

Then, descending from her clime ….

She had arrived to help me, there,

And touched my body everywhere …

And went away. There I remained

Aloft; ocean waves waxed and waned;

Finally, with one mighty crash,

Our ship against the rocks was smashed,

Awakening me. I felt all strange:

My body undergoing change

All over I felt transmutated:

No longer weak and subjugated.

Each limb of mine did feel much stronger,

I, discomfited no longer ….

All over I felt myself afresh,

As I touched muscle – a man’s flesh!

And my voice took on assurance

As my body gained endurance ….

Let me summarize, this moment,

Just who I am, what all this meant.

How I, a woman, became a man

By a flick of Fortune’s hand;

How she changed my body’s form

To the perfect masculine norm.

I’m a man, no truth I’m hiding,

You can tell by how I’m striding ….So I raised my eyes all around,

At the mangled ship all dashed aground:

Sail and mast I saw in tatters;

To angry storms, nothing matters ….

When I’d seen this devastation,

I prepared for reparation.

Hammer in hand, with mortar and nails,

I rejoined the planks; then where snails

Dwell, under rocks, I gathered moss

To cover leaks, I spread it across,

And made the hull watertight, then

I drained the bilge: she floats again!

In no time at all, I could sail,

For I learned to pilot, to prevail

Over oceans at my command,

I and my crew knew to withstand

Danger and fend off death. Now see,

Like a real man; I have to be.

Fortune kindly taught me the way

To do manly deeds, to this day.

As you can tell, men are my peers

As they have been for thirteen years.

Though ’twould please me more than a third,

To return as woman and be heard.

Conversant with French, Italian, and Latin, de Pizan was able, thanks to various noble patrons, to support herself through her writing; her voluminous output included love-poetry, didactic poetry, royal biographies, literary criticism, political theory, educational theory, a textbook on the art of war (which was actually used), a project for international law, and a spirited encomium of Joan of Arc.

Rosalind Brown-Grant, the translator of City of Ladies, writes:

One important feature of Christine’s style in the City of Ladies deserves a special mention …. When she wants to make a particular point about men as opposed to humankind in general, Christine de Pizan is careful to distinguish between, on the one hand, the specific term ‘les hommes’, meaning simply the male sex, and, on the other hand, generic terms such as ‘les gens’, which refer to both sexes, or sex-neutral terms such as ‘la personne’, which can indicate either sex. Moreover, Christine is equally concerned not to subsume the female pronoun ‘elles’ under the male pronoun ‘ils’ in those cases where she wants to highlight the moral equality of men and women …. In this respect … she is ahead of her time in anticipating many of the arguments that modern feminist linguistics has raised about sexist language.

Unlike such female forerunners as the literary patrons Eleanor of Aquitaine and Marie de Champagne, or the poets Beatriz de Dia and Marie de France, de Pizan was hostile to the tradition of courtly love – although she herself composed works in the genre. (I’ve written a bit about her views on this topic previously, here.) In her “Letter of the God of Love,” she describes courtly love as essentially a trap to hoodwink women:

But now in France, the place where in the past

Women were honored so, those men who’re false

Dishonor them, more than in other lands ….

The loyal lovers’ pose they strike is false.

Hiding behind their myriad deceits,

They go declaring that a woman’s love

Inflames them sorely, keeps their hearts locked up;

The first laments, the second’s heart is wrenched,

The next pretends to fill with tears, and sighs;

Another claims to sicken horribly:

Because of love’s travail he’s grown quite pale,

Now perishing, now very early dead.

Swearing their fervent oaths, hey lie and vow

To be discreet and true, and then they crow. …

Now Ovid, in a book he wrote, sets down

Profuse affronts; I say that he did wrong ….

In which he teaches them and openly

Elucidates the way to trick the girls

By means of subterfuge, and have their love. …

And Jean de Meun’s The Romance of the Rose,

Oh, what a long affair! How difficult! …

So many efforts made and ruses found

To trick a virgin – that, and nothing more!

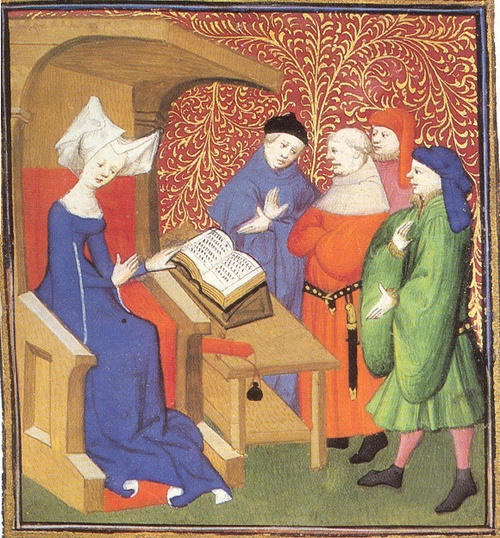

Christine de Pizan recites a spell from the Necronomicon that is guaranteed to turn four men into one.

De Pizan had a particular animus against Jean de Meun, whose work contained passages so offensive that she “jumped over them like a cat on hot bricks.” She was especially incensed at the view, propounded by de Meun and other mediæval writers, that women want to be raped and put up only a fake resistance. In her City of Ladies, she replies by recounting such stories as that of the Roman noblewoman Lucretia, whose response to being raped was to commit suicide; or, alternatively, that of the Queen of the Galatians, who, after being kidnapped and raped, “bided her time and hid her feelings” until a propitious moment, whereupon, as de Pizan recounts with considerable satisfaction, “the lady picked up a knife, slit [her rapist’s] throat and killed him,” and then “cut off his head, and without a hint of remorse, took it to show her husband.”

I’ve discussed previously how, in her novel The Duke of True Lovers, what de Pizan says about courtly-love relationships and what she shows about them through the novel’s events are somewhat at odds. But that is not the only notable tension in de Pizan’s work:

In her City of Ladies, she holds up rulers, scholars, warriors, Amazons, and other independent and assertive women as role models for contemporary women (and elsewhere she cites Joan of Arc as an ideal); and yet in the sequel, Treasure of the City of Ladies, the actual advice she offers to women is much more conventional. Young women in particular are advised to be

in their countenances, conduct and speech moderate and chaste, and … quiet … with their eyes lowered. … In the street and in public they should be mild and sedate, and at home not idle but always busy with some housework. … Their speech should be amiable and courteous to all people; they should have a humble manner and not be too talkative.

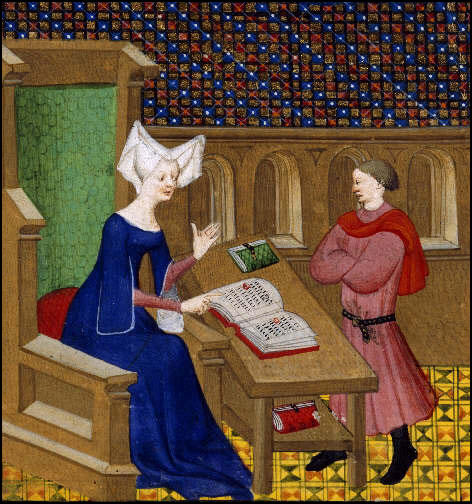

The spell worked! And changed the wallpaper too!

One possible (I think, likely) explanation for the tension is that de Pizan was torn between a) an expansive and inspiring vision of what women are capable of in the abstract, and b) a straitened recognition of the strict limits to what women can expect to get away with in ordinary life, given prevailing social sanctions for “improper” female behaviour. (Both (a) and (b) are, after all, pervasive themes throughout her work.)

Yet she also sometimes seems to express approval of those limits. Thus, while on the one hand she frequently complains about the harm and injustice that are done to women by keeping them ignorant of and excluded from knowledge of financial and legal matters, on the other hand she nevertheless upholds, as God-given, the very gendered division of labour that leads to the situation she complains about:

[J]ust as a wise and prudent lord organizes his household into different domains and operates a strict division of labour amongst his workforce, so God created man and woman to serve Him in different ways …. God gave men strong, powerful bodies to stride about and to speak boldly, which explains why it is men who learn the law and maintain the rule of justice. … Even though God has often endowed many women with great intelligence, it would not be right for them to abandon their customary modesty and to go about bringing cases before a court …

Such passages have sometimes led to charges that de Pizan does not count as an authentic pioneer of feminism. I think it is fairer to say that her thought contains both feminist and antifeminist strands, but that the feminist strands are distinctive and pervasive enough, especially by comparison with most of her contemporaries, that she deserves a place in the feminist canon.

No comments yet.