Yesterday’s entry, Beowulf (1998), was from the Middelboe-produced series “Animated Epics.” This next adaptation, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (2002), actually written by Middelboe, is sometimes treated as part of that series and sometimes treated as a standalone project.

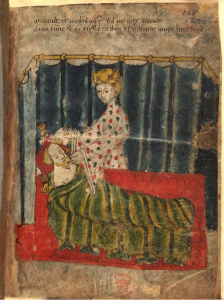

A nice touch here: all the characters and scenes are stained-glass windows come to life.

At a certain level of abstraction, the structure of the plot is strikingly similar to that of Beowulf, despite the vast difference in tone and culture: a ruler and his men are feasting in their hall when a monstrous figure appears and challenges them; our warrior protagonist responds to the challenge, engages the monster, and subsequently tracks him back to his lair, where he must also face the monster’s female relative. There’s even a decapitation and a head being carried, although the circumstances are radically different.

As to the differences, Gawain’s atmosphere is both more thoroughly Christian and more erotically charged – a seeming contradiction that seeks resolution within the complex maze of rules of “courtly love” that would probably seem rather alien to the world of Beowulf. (One also suspects that there were probably bawdier versions of the “exchange of gifts” portion of the story to be found in circulation.)

An interesting feature of this story is that while the behaviour of the protagonist is decidedly dodgy by conventional Christian standards – he engages in a romantic dalliance (albeit an unconsummated one) with a woman who is not only married, but married to his own host and benefactor, plus he cheats his host by withholding one of the gifts he agreed to exchange (namely the enchanted girdle) – yet it is only the matter of the girdle that is condemned, and that only glancingly; the dalliance itself, as Gawain carefully negotiates it, is treated as an honourable middle way between, on the one hand, the sin of violating the requirements of chastity and hospitality, and on the other hand, the discourtesy of spurning the (not exactly unpleasant) advances of a fair and noble lady. Yet Gawain is not an anti-Christian tale; the hero carries an image of the Virgin Mary on the inside of his shield, and regards his commitment to the courtly ethos as continuous with his Christian duty – another example of the way that the mediæval Church’s claim of sole authority to decide on such matters did not go unchallenged in popular Christian culture.

The pumpkin jack o’lanterns in the film are anachronistic (jack o’ lanterns are in fact a fairly old Celtic tradition, but pumpkins are native to the New World), but may be a nod to the literary affiliation between Gawain’s Green Giant and the pumpkin-wielding headless horseman in Washington Irving’s Ichabod Crane.

[…] the whole of mediæval attitudes toward life. First, as I have recently discussed (see here and here), the Church’s sole authority in moral and spiritual matters did not go unchallenged during the […]