Ayn Rand does not seem always to have been hostile to the culture of the Middle Ages. In college she took (according to her transcript) five courses on mediæval European history, four of which seem to have been elective seminars. In We the Living, she writes approvingly (but, from the standpoint of her later philosophy, incongruously) of the novel’s heroine: “From somewhere in the aristocratic Middle Ages, Kira had inherited the conviction that labor and effort were ignoble”; moreover, she chooses as Kira’s heroic symbol the mediæval figure of a Viking (probably under the inspiration partly of Nietzsche, and partly of Fritz Lang’s Siegfried). And a play celebrating Joan of Arc played an important role in the first draft of The Fountainhead.

But at some later point she seems to have decided that mediæval culture was antithetical to her values. In “The Left: Old and New,” she dismisses the Middle Ages as “an era of mysticism, ruled by blind faith and blind obedience”; and in Atlas Shrugged she has Galt assert that “the supernatural doctrines of the Middle Ages … kept men huddling on the mud floors of their hovels, in terror that the devil might steal the soup they had worked eighteen hours to earn.” She did largely except Thomas Aquinas from her condemnation of mediæval culture, but only because she saw his work as the beginning of an Aristotelean revolution that would overthrow mediæval culture and usher in the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. (I’ve groused elsewhere about the Randian tendency to downplay the merits of the mediæval period by treating Aquinas as though he were, at least in spirit, a post-mediæval figure.) (Incidentally, I’m not aware that Rand ever discussed the role of Aristoteleanism in the mediæval Islamic world, even though she must have been aware of Rose Wilder Lane’s enthusiastic defense of “Saracen” culture.)

Rand’s followers have likewise denounced mediæval culture as hostile to human reason and human happiness. Thus Leonard Peikoff writes, in The Ominous Parallels:

The dominant moralists had said that man must not seek his ultimate fulfillment on earth; that he must renounce the pleasures of this life, whether as a flesh-mortifying ascetic or as an abstemious toiler, for the sake of God, salvation, and the life to come ….

And in “Religion vs. America,” Peikoff adds:

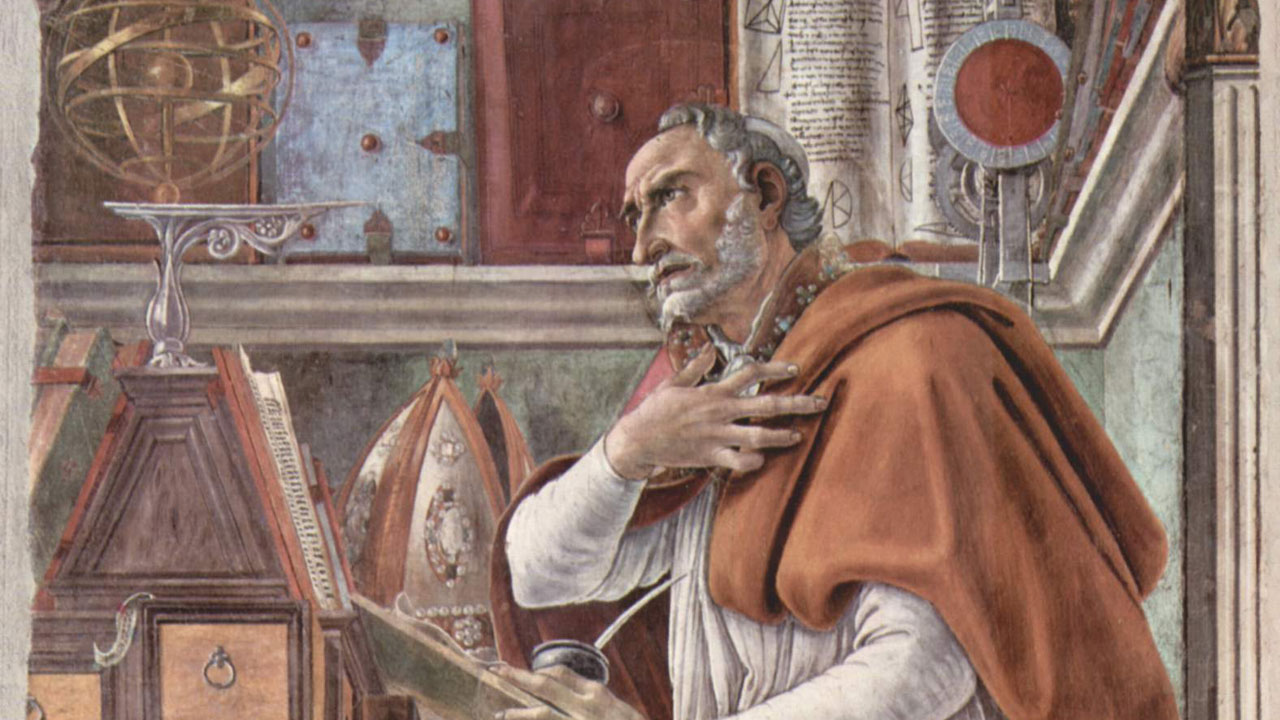

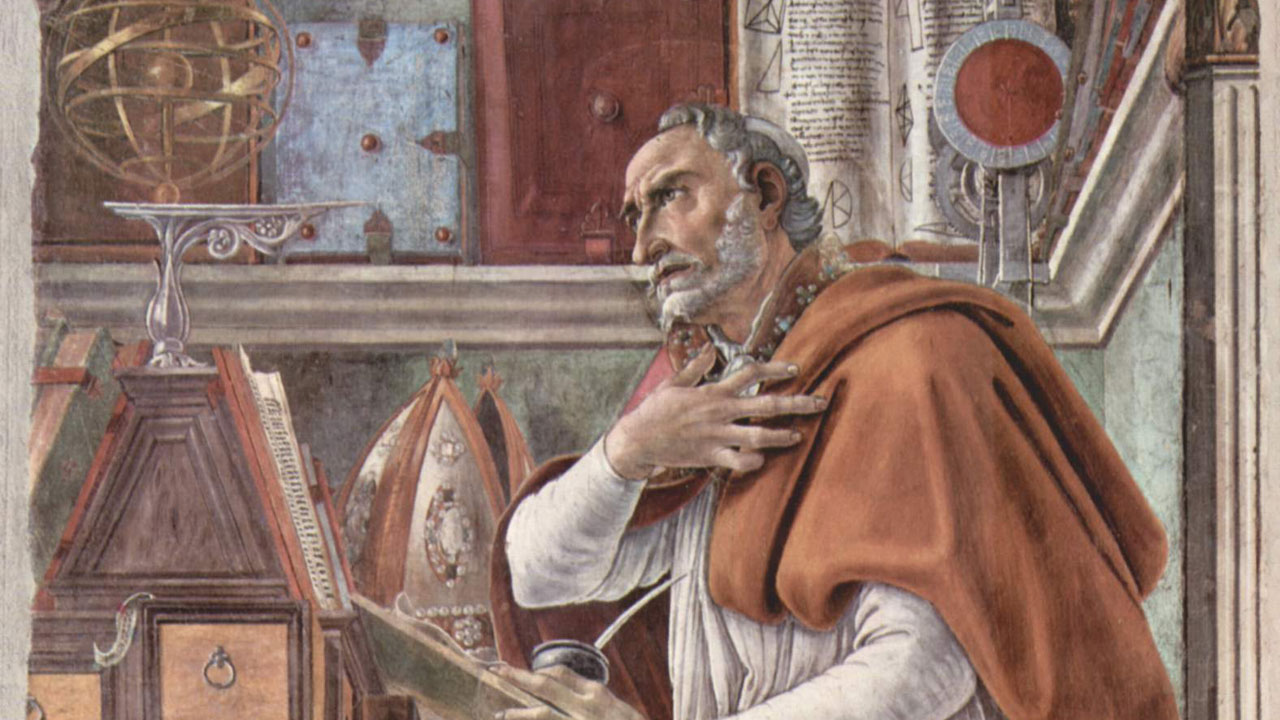

The Dark Ages were dark on principle. Augustine fought against secular philosophy, science, art; he regarded all of it as an abomination to be swept aside; he cursed science in particular as “the lust of the eyes.”

Similarly, Mary Ann Sures, in “Metaphysics in Marble,” writes:

Medieval mystics regarded man as an evil creature whose body is loathsome because it is material, and whose mind is impotent because it is human. Hating man’s body, they said that pleasure is evil, and virtue consists of renunciation. Hating this earth, they said that it is a prison where man is doomed to pain, misery, calamity. Hating life, they said that death and escape into some other dimension is all that man could – and should – hope for. … Suffering as an ideal or suffering as punishment was all that medieval art offered to its heroes or its sinners here on earth.

Now I will readily grant that these descriptions do capture a significant strand within mediæval culture. St. Jerome, for example, in one of his letters describes the life of a model Christian woman:

Marcella practised fasting, but in moderation. She abstained from eating flesh, and she knew rather the scent of wine than its taste …. She seldom appeared in public and took care to avoid the houses of great ladies, that she might not be forced to look upon what she had once for all renounced. She frequented the basilicas of apostles and martyrs that she might escape from the throng and give herself to private prayer. … Marcella then lived the ascetic life for many years, and found herself old before she bethought herself that she had once been young. She often quoted with approval Plato’s saying that philosophy consists in meditating on death. … Well then, as I was saying, she passed her days and lived always in the thought that she must die. Her very clothing was such as to remind her of the tomb, and she presented herself as a living sacrifice, reasonable and acceptable, unto God. …

But I deny that this strand captures the whole of mediæval attitudes toward life. First, as I have recently discussed (see here and here), the Church’s sole authority in moral and spiritual matters did not go unchallenged during the mediæval period, as many writers and artists among the laity celebrated a more worldly ethic; and second, even thinkers within the Church held more complicated views than the Randians allow.

Take, for instance, Augustine, whom the Randians regard as the presiding genius of mediæval awfulness. He’s an enormously mixed bag philosophically, to be sure; but he is unmistakably an ethical eudaimonist in the lineage of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics, and an absolutely crucial influence on Rand’s beloved Aquinas. It’s true that he expresses suspicion of scientific inquiry; but given his role in championing the writings of pagan thinkers like Plato and Cicero, against those Christians who wanted to consign all such products of Greek and Roman culture to the flames, it’s hardly accurate to say that he regarded all of “secular philosophy” as “an abomination to be swept aside.” (And in any case, Augustine’s attempt to discourage scientific inquiry was not successful, as such inquiry persists throughout the Middle Ages.)

Nor did mediæval thinkers as a rule condemn the human mind as “impotent because it is human.” On the contrary, they held that while it is appropriate to take the Church’s teachings on faith (by which the mediævals generally meant not “blind” faith, i.e., faith without evidence, but rather belief on the basis of testimonial evidence rather than either perceptual evidence or rational demonstration), it is still nobler to seek for a rational proof and understanding of the doctrines of faith, where possible. Indeed, this is a central theme of Augustine’s philosophical dialogue On Free Choice of the Will.

Augustine also regards both reason and the senses as efficacious tools of cognition, and praises reason in particular as the faculty that sets us above the lower animals:

There are two kinds of things that are known: the things that the mind perceives through the bodily senses, and the things that it perceives through itself. These philosophers [= the Greek Skeptics] have babbled much against the bodily senses, but they have never been able to call into doubt the most solid perception of true things the mind has through itself, such as … “I know that I’m alive.” … Yet far be it from us to doubt the truths that we have learned through the bodily senses [either]! (On the Trinity 15)

It is clear that many wild animals easily surpass human beings in strength and in other physical abilities. What is it in virtue of which a human being is superior, so that he can command many wild animals, yet none of them commands him? is it not perhaps what we usually call reason or understanding? … How can knowledge in the strict and proper sense be evil, since it is acquired by reason and understanding? … That by which humans are ranked above animals, whatever it is, be it more correctly called “mind” or “spirit” or both … if it dominates and commands the rest of what a human consists in, then that human being is completely in order … Therefore, when reason (or mind or spirit) governs irrational mental impulses, a human being is dominated by the very thing whose dominance is prescribed by the law we have found to be eternal. …

Physical objects are sensed by bodily sense … Reason acquaints us with all the foregoing, as well as with reason itself, and knowledge includes them. … The intelligible structure and truth of number is present to all reasoning beings. Everyone who calculates tries to apprehend it with his own reason and intelligence; some do this with ease, others with difficulty, yet it offers itself equally to all who are capable of grasping it. (On Free Choice of the Will)

When Augustine goes on to identify Truth as superior to human reason, he doesn’t mean that Truth is beyond reason’s ability to grasp; rather, he means (as he clearly explains) that Truth is the standard for reason rather than vice versa. (In other words, like a good Randian he rejects the primacy of consciousness.)

Moreover, Augustine wrote an entire book – Against the Academics – devoted to defending the efficacy of both reason and the senses against skeptical attacks.

Did Augustine regard matter and the material body as intrinsically evil? No, this was a Manichean view that he was at pains to reject. (Plotinus rejected it too, incidentally.) Augustine writes:

There is no need, therefore, that in our sins and vices we accuse the nature of the flesh … for in its own kind and degree the flesh is good …. For he who extols the nature of the soul as the chief good, and condemns the nature of the flesh as if it were evil, assuredly is fleshly both in his love of the soul and hatred of the flesh; for these his feelings arise from human fancy, not from divine truth. (City of God XIV.5)

What is evil is neither the body per se nor the choice of bodily goods per se, but rather the choice of bodily goods when they conflict with goods of a higher order.

And in similar vein Aquinas endorses the pursuit of bodily pleasures, so long as they are pursued in a manner subordinate to reason. While it’s true, for both Augustine and Aquinas, that we cannot find our “ultimate fulfillment on earth,” neither drew the inference that we must therefore “renounce the pleasures of this life.”

Some have maintained …. that all bodily pleasures should be reckoned as bad, and thus that man, being prone to immoderate pleasures, arrives at the mean of virtue by abstaining from pleasure. But they were wrong in holding this opinion. … The temperate man does not shun all pleasures, but those that are immoderate, and contrary to reason. The fact that children and dumb animals seek pleasures, does not prove that all pleasures are evil: because they have from God their natural appetite, which is moved to that which is naturally suitable to them. … Pleasures of the sensitive appetite are not the rule of moral goodness and malice, since food is universally pleasurable to the sensitive appetite both of good and of evil men; but the will of the good man takes pleasure in them in accordance with reason, to which the will of the evil man gives no heed. (Aquinas, Summa Theologiæ IaIIæ 34)

Nor should we look only at theologians like Augustine and Aquinas when examining the “dominant moralists” of the mediæval period. Given the enormous popularity and influence of Andreas Capellanus’s Art of Courtly Love, why shouldn’t he too be regarded as one of the “dominant moralists” of the Middle Ages? That would certainly bring to the fore a far more accommodating view of worldly pleasures than that of Augustine or Aquinas (and one reflected in much mediæval literature).

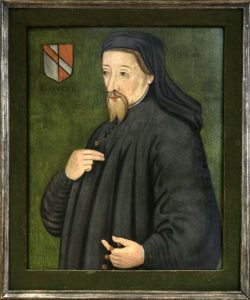

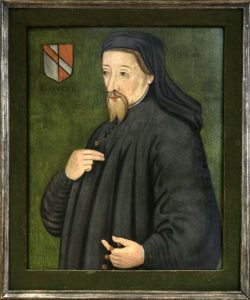

As for the common people, is it true that they were all huddling in the mud in superstitious terror, as described in Galt’s speech? I’ve previously cited some rather more skeptical and irreverent attitudes among mediæval commoners; and I’ll cite another here , from Chaucer’s enormously popular Canterbury Tales:

Chaucer doesn’t give a shit.

“Masters,” said he, “in churches when I preach,

I take pains to have a haughty speech ….

Then show I forth long boxes in a mass,

crammed full with rags and bones encased in glass –

holy relics, they suppose that they’ve been shown! –

as well as, set in brass, a shoulder-bone

that once was in a holy Jew-man’s sheep.

‘Good men,’ say I, ‘my words in memory keep:

if this bone here be washed in any well,

if cow or calf or sheep or ox should swell

from eating snakes or by a snake being stung,

take water from that well and wash its tongue,

and ’twill be healed anon; and furthermore

of pox and scabs, indeed of every sore,

shall any sheep be healed, that from this well

shall drink a draft; take heed of what I tell. …’

By trickery thus have I won, year by year,

a hundred marks since I’ve been Pardoner.

In pulpit I do stand, in cleric’s gown,

and once the foolish people have sat down

I preach to them as you have heard before,

inflicting on them frauds a hundred more.”

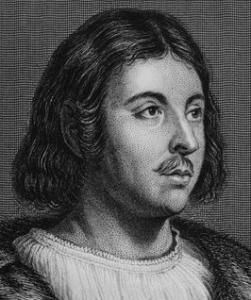

And compare the similarly irreverent, mocking, bawdy spirit of Chaucer’s contemporary, Giovanni Boccaccio, in his epilogue to the Decameron:

Boccaccio also doesn’t give a shit.

There may also be those among you who will say that I have an evil and venomous tongue, because in certain places I write the truth about the friars. But who cares? I can readily forgive you for saying such things, for doubtless you are prompted by the purest of motives, friars being decent fellows, who forsake a life of discomfort for the love of God …. Except for the fact that they all smell a little of the billy-goat, their company would offer the greatest of pleasure.

I will grant you, however, that the things of this world have no stability, but are subject to constant change, and this may well have happened to my tongue. But not long ago, distrusting my own opinion (which in matters concerning myself I trust as little as possible), I was told by a lady, a neighbor of mine, that I had the finest and sweetest tongue in the world ….

That’s right: as a reply to the charge of insufficient reverence toward clerical majesty, Boccaccio, typically, retorts with testimonial evidence of his skill at oral sex. And his book, like Chaucer’s, was wildly popular. (Both wrote in the vernacular rather than in Latin.) Clearly not everyone in the Middle Ages was cowering in superstitious awe of ecclesiastical authority and holy relics, nor did everyone regard the pleasures of the body as evils to be renounced.

As Alixe Bovey notes:

In the past, the Middle Ages was often characterised as the ‘Age of Faith’, but now it is recognised that this moniker conceals the complexity of the medieval religious culture. Christianity was the dominant religion, but not everyone followed the faith with the same intensity: judging from legislation and sermons encouraging lay people to attend church and observe its teachings, many people were lukewarm in the faith, while others were openly or covertly sceptical.

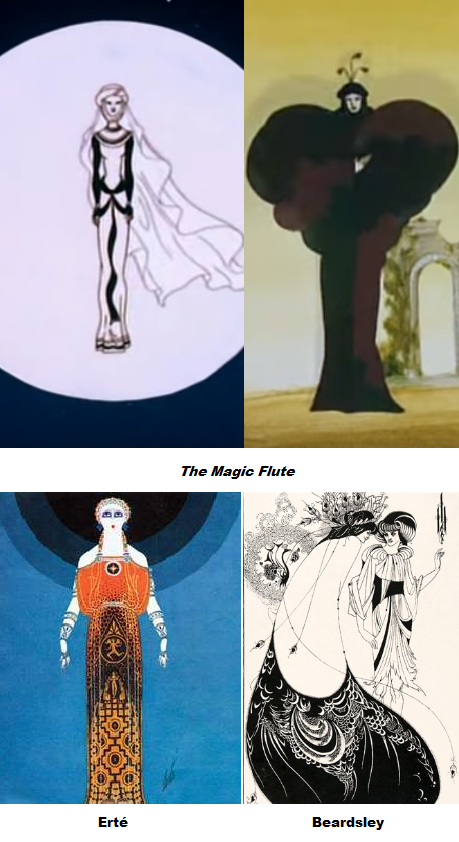

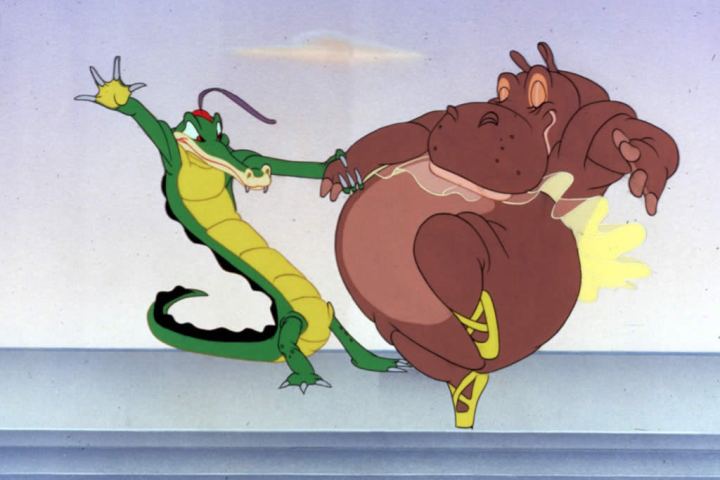

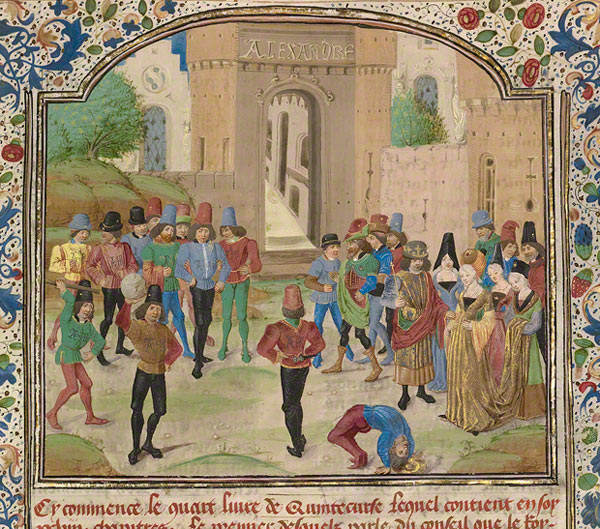

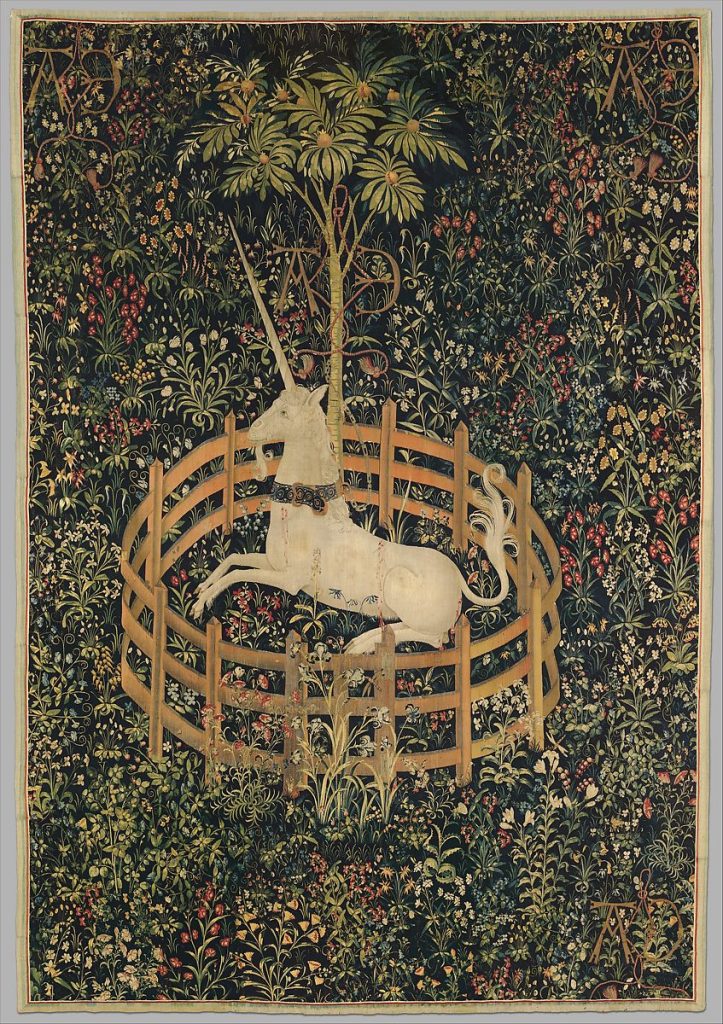

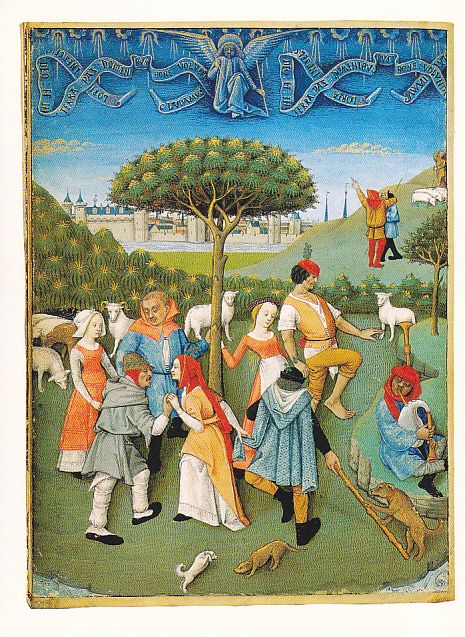

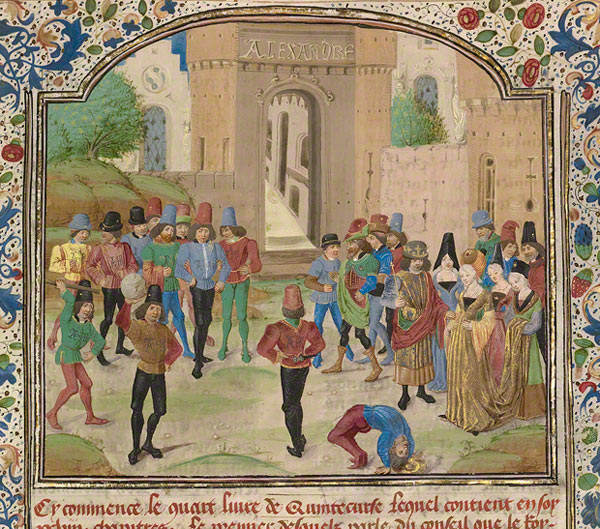

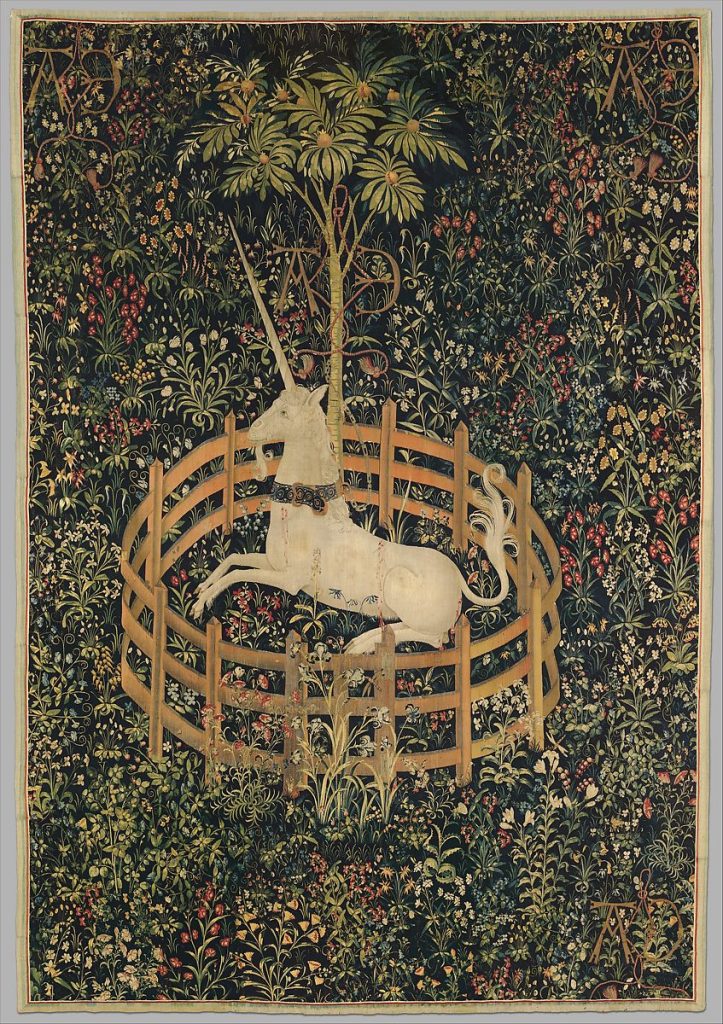

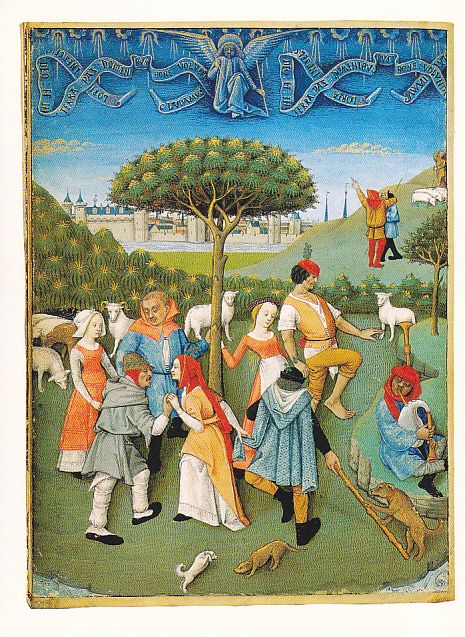

As for the claim that “suffering … was all that medieval art offered” – well, in addition to the examples of mediæval art I posted last time, I’ll close with these:

Oh, the suffering.