Or, if you prefer Gaiman’s version to Marvel’s:

Or, if you prefer Gaiman’s version to Marvel’s:

Moving on from Othello, we come to another (rather different) tale of love, jealousy, and murder with an especially visually beautiful, rotoscoped Carmen (“Operavox,” 1995).

Nietzsche, who began his philosophical career with two encomia to Wagner (The Birth of Tragedy [1872] and Richard Wagner in Bayreuth [1876]), was by the end attacking Wagner and praising Bizet’s Carmen as a healthier alternative (The Case of Wagner [1888]):

Yesterday I heard – would you believe it? – Bizet’s masterpiece, for the twentieth time. … How such a work makes one perfect! One becomes a “masterpiece” oneself. … May I say that the tone of Bizet’s orchestra is almost the only one I can still endure? That other orchestral tone which is now fashion, the Wagnerian, brutal, artificial, and “innocent” at the same time and thus it speaks all at once to the three senses of the modern soul, – how detrimental to me is this Wagnerian orchestral tone! I call it scirocco. I break out into a disagreeable sweat. My good weather is gone.

This music seems perfect to me. It approaches lightly, supplely, politely. It is pleasant, it does not sweat. “What is good is light, whatever is divine moves on tender feet”: first principle of my aesthetics. This music is evil, subtle, fatalistic …. Have more painful tragic accents ever been heard on the stage? And how they are achieved! Without grimaces! Without counterfeit! Without the lie of the great style! …

Bizet’s work also saves; Wagner is not the only “Saviour.” With it one bids farewell to the damp north and to all the fog of the Wagnerian ideal. … [W]hat it has above all else is that which belongs to sub-tropical zones – that dryness of atmosphere, that limpidezza of the air. Here in every respect the climate is altered. Here another kind of sensuality, another kind of sensitiveness and another kind of cheerfulness make their appeal. This music is gay, but not in a French or German way. Its gaiety is African; fate hangs over it, its happiness is short, sudden, without reprieve. I envy Bizet for having had the courage of this sensitiveness, which hitherto in the cultured music of Europe has found no means of expression, – of this southern, tawny, sunburnt sensitiveness. … What a joy the golden afternoon of its happiness is to us! When we look out, with this music in our minds, we wonder whether we have ever seen the sea so calm. And how soothing is this Moorish dancing! How, for once, even our insatiability gets sated by its lascivious melancholy! – And finally love, love translated back into Nature! Not the love of a “cultured girl!” … But love as fate, as a fatality, cynical, innocent, cruel ….

In Nietzschean terms, this is high praise for Bizet (“evil” and “cruel” are not pejorative terms in his vocabulary) – but somewhat undercut by the book’s introduction, where he writes:

I have granted myself some small relief. It is not merely pure malice when I praise Bizet in this essay at the expense of Wagner. Interspersed with many jokes, I bring up a matter that is no joke.

It’s as though Nietzsche is saying, “I’m only half-joking when I praise Bizet as being better than Wagner.”

In any case, unlike Nietzsche I feel no need to choose between Wagner and Bizet. I am greedier than that.

David Bowie and Elvis Costello each confront their respective Doppelgängers:

48. David Bowie, “Width of a Circle” (1970):

49. Elvis Costello, “My Science Fiction Twin” (1994):

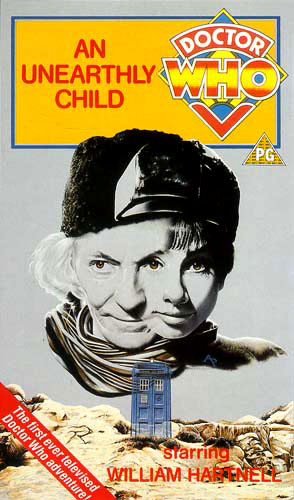

As many of my readers will know, the original 1963 pilot for Doctor Who, “The Unearthly Child,” exists in two versions. The original version was reshot because of several complaints by the powers-that-BBC, notably:

Viewing the two episodes in tandem I’ve also noticed the following specific differences (not a complete list!):

In the aired version, the Doctor explains how the TARDIS can be bigger on the inside by comparing it to showing a large building on a small television screen; and when Ian and Barbara don’t understand, he compares their minds to the “savage mind” of a “Red Indian” when first confronted with a locomotive. None of this had been in the unaired version.

In the aired version, the Doctor explains how the TARDIS can be bigger on the inside by comparing it to showing a large building on a small television screen; and when Ian and Barbara don’t understand, he compares their minds to the “savage mind” of a “Red Indian” when first confronted with a locomotive. None of this had been in the unaired version.Anyway, if you too want to watch the shows in conjunction in order to compare them (either watching one just before the other, or else cutting back and forth between the two), you can do so conveniently here, as I’ve embedded them both on the same page. (The BBC tends to get these taken down, so watch them while you can!)

The unaired version:

The aired version:

Incidentally, the Doctor’s pseudonym in this episode, “I. M. Foreman,” might seem to be a reference to his status as champion of the Earth and of humanity (“I am for man”); but that status wasn’t yet established at this point – indeed, he seems rather hostile to humans (and two episodes later would be trying to bash an injured caveman’s head in with a rock). So I think it’s probably just a coincidence.

The themes of malice, deceit, and revenge continue in Othello (“Shakespeare: The Animated Tales,” 1994) – with a cameo from Hamlet’s Ophelia at 17:10-38:

(For my own take on Othello, see here.)

Two possible futures for New York City:

46. David Bowie, “New York’s in Love” (1987):

47. Billy Joel, “Miami 2017 (Seen the Lights Go Out On Broadway)” (1976):