One of the tragic aspects of the emancipation of the serfs in Russia in 1861 was that while the serfs gained their personal freedom, the land – their means of production and of life, their land was retained under the ownership of their feudal masters. The land should have gone to the serfs themselves, for under the homestead principle they had tilled the land and deserved its title. Furthermore, the serfs were entitled to a host of reparations from their masters for the centuries of oppression and exploitation. The fact that the land remained in the hands of the lords paved the way inexorably for the Bolshevik Revolution, since the revolution that had freed the serfs remained unfinished.

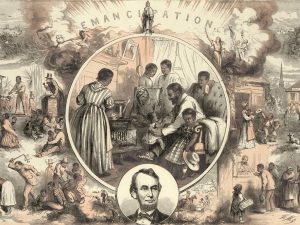

The same is true of the abolition of slavery in the United States. The slaves gained their freedom, it is true, but the land, the plantations that they had tilled and therefore deserved to own under the homestead principle, remained in the hands of their former masters. Furthermore, no reparations were granted the slaves for their oppression out of the hides of their masters. Hence the abolition of slavery remained unfinished, and the seeds of a new revolt have remained to intensify to the present day. Hence, the great importance of the shift in Negro demands from greater welfare handouts to “reparations”, reparations for the years of slavery and exploitation and for the failure to grant the Negroes their land, the failure to heed the Radical abolitionist’s call for “40 acres and a mule” to the former slaves. In many cases, moreover, the old plantations and the heirs and descendants of the former slaves can be identified, and the reparations can become highly specific indeed.

I think it might be better to say that they were entitled to financial compensation and if the slave holders needed to self their land to raise the money, then so be it.

I don’t know how easy it would be to say that a certain person in Alabama say is the heir of x who was a slave and that all his rights were passed down in wills. Same with the descendants of the slave holders.

I think it might be better to say that they were entitled to financial compensation …

Well, O.K. But why?

Notice in particular that Rothbard is arguing that freedpeople had two classes of moral claims against former slaveholding planters (*). (1) He argues that freedpeople had a homestead claim to land that they had cleared and tilled. (**) (2) He also argues that in addition to the homestead claim, freedpeople also had a separate, additional reparations claim to compensation for the damage done to them by the forced labor, captivity, assault, theft, etc. inflicted on them by planters in the course of enslaving them.

It’s straightforward why financial compensation would be a good way of satisfying claim (2), the claim for compensation for damages. But Rothbard’s argument for claim (1) isn’t based on a claim for compensatory damages. It’s based on the labor-mixing principle. He’s arguing that plantations already rightfully belonged to the tenants who had cleared and tilled them under slavery, not to the slavers who forced them to do so, and so they were already entitled to remain on it as rightful owners before any further compensation that planters owed them for the damages inherent in or incident to enslavement.

Imagine a house-breaker who chases down a family, beats them up and ties them to the radiator, threatens them at gunpoint,etc. until they are able to force them to give up everything they own. Later on, they get caught, while they still have the family jewels, grandma’s silver, etc. in their possession. They owe their victims (2′) restitution for the beating and the captivity and all that. They also owe them (1′) the return — in kind, wherever this is possible — of the family jewels, grandma’s silver, etc. If they tried to to satisfy claim (2′) by selling off the family jewels and then using the cash to pay off the damages they owe, then they would hardly be entitled to call it quits, because that means ignoring or violating claim (1′). The family they robbed have a right to recover what was stolen from them, and the house-breaker is obliged to figure out some other way of paying off what they owe under claim (2′). As I understand Rothbard’s argument, his view on homesteaded land and financial reparations is going to be directly analogous.

Of course, he could be wrong about the principle involved; or he could be wrong about how it applies, factually, to the situation in the antebellum plantation economy. But if so, how?

Notice in particular that Rothbard is arguing that freedpeople had two classes of moral claims against former slaveholding planters (*). (1) He argues that freedpeople had a homestead claim to land that they had cleared and tilled. (**) (2) He also argues that in addition to the homestead claim, freedpeople also had a separate, additional reparations claim to compensation for the damage done to them by the forced labor, captivity, assault, theft, etc. inflicted on them by planters in the course of enslaving them.

It’s straightforward why financial compensation would be a good way of satisfying claim (2), the claim for compensation for damages. But Rothbard’s argument for claim (1) isn’t based on a claim for compensatory damages. It’s based on the labor-mixing principle. He’s arguing that plantations already rightfully belonged to the tenants who had cleared and tilled them under slavery, not to the slavers who forced them to do so, and so they were already entitled to remain on it as rightful owners before any further compensation that planters owed them for the damages inherent in or incident to enslavement.

Imagine a house-breaker who chases down a family, beats them up and ties them to the radiator, threatens them at gunpoint,etc. until they are able to force them to give up everything they own. Later on, they get caught, while they still have the family jewels, grandma’s silver, etc. in their possession. They owe their victims (2′) restitution for the beating and the captivity and all that. They also owe them (1′) the return — in kind, wherever this is possible — of the family jewels, grandma’s silver, etc. If they tried to to satisfy claim (2′) by selling off the family jewels and then using the cash to pay off the damages they owe, then they would hardly be entitled to call it quits, because that means ignoring or violating claim (1′). The family they robbed have a right to recover what was stolen from them, and the house-breaker is obliged to figure out some other way of paying off what they owe under claim (2′). As I understand Rothbard’s argument, his view on homesteaded land and financial reparations is going to be directly analogous.

Of course, he could be wrong about the principle involved; or he could be wrong about how it applies, factually, to the situation in the antebellum plantation economy. But if so, how?

(* The same would presumably apply in the other kinds of cases that were suitably analogous in terms of forcing slaves to clear and develop land in other kinds of slave economy enterprises — e.g. in small farms, mines, saltworks, etc., allowing for whatever devils might arise in the details when it comes to capital-intensive vs. land-intensive operations, multi-generational labor, etc.)

(** The legal title to that land was distributed, by the state, to slaveowners, either through the mechanism of various land grant and preemption schemes, or by means of purchasing land from speculators, or by means of purchasing land from prior tenants. But Rothbard’s argument is, so what? The moral claim rightfully derives from homesteading labor, which was overwhelmingly performed by the people enslaved by the planters, not by the planters themselves.)