[cross-posted at C4SS and BHL]

A new anthology titled Panarchy: Political Theories of Non-Territorial States, edited by Aviezer Tucker and Gian Piero de Bellis, has been released by Routledge.

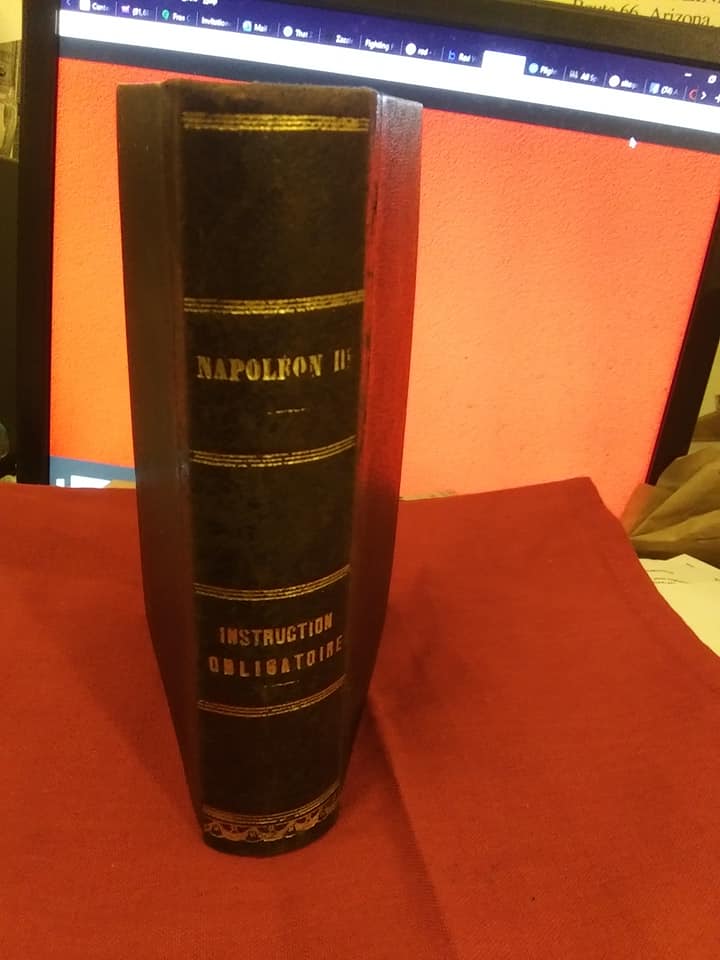

The concept of panarchy comes from an 1860 work of that title by the Belgian botanist and political economist Paul Émile de Puydt (1810-1891). The essence of his panarchist proposal is that people should be free to choose the political regime under which they will live without having to relocate to a different territory. The new anthology assembles a number of sources, both historical and contemporary, developing this idea.

The editors define panarchism as “a normative political meta-theory that advocates non-territorial states founded on actual social contracts that are explicitly negotiated and signed between states and their prospective citizens.” (p. 1) This characterisation, with its call for explicitly signed contracts, is a somewhat narrower use of the term than is common in contemporary anarchist circles, or at least those in which I move. John Zube, who has done more than anyone to popularise the concept, defines it a bit less rigidly as the “realization of as many different and autonomous communities as are wanted by volunteers for themselves, all non-territorially coexisting … yet separated from each other by personal laws, administrations and jurisdictions ….” (quoted on p. 90)

If one’s standard for political legitimacy is efficiency, wouldn’t the competition of multiple systems within the same jurisdiction be more efficient, for familiar economic reasons, than the imposition of a single model? If one’s standard is what rational agents could consent to, why not support a system in which everyone gets the system they actually consent to? After all, part of the point of the hypothetical consent stories that have dominated contemporary political philosophy is the assumption that actual consent could never be unanimous – an assumption that panarchism shows how to circumvent. If the worry is that competing systems within the same territory would be unworkable, a number of the pieces in the volume point out how, in Aviezer Tucker’s words, “there have been many historically functioning models of mixed, overlapping, and extra-territorial … jurisdictions” (p. 148) – or, in Richard C. B. Johnsson’s formulation, for most of human history “laws followed the persons, not the territory.” (p. 207)

The various contributions to the volume make a fascinating and, to me, compelling case. (Self-promotion alert: I have a chapter in the book, one of my pieces from the 1990s advocating “virtual cantons.” In the interests of further disclosure, one of the editors, Tucker, is a friend; I recall with fondness a long hike with him down Prague’s Petřín Hill, in the course of which his daughter learned to walk.)

Left-libertarians should be warned, however, about occasional passages that will make their jaws drop, such as Max Borders’ cheery assurance that “if police are cruising your neighborhood, you’ll benefit” (p. 174), or Michael Gibson’s equally cheery assurance that large corporations, despite their “visibly dictatorial” structure, are “not poorly behaved at all.” (p. 167) Perhaps these writers are from a parallel universe?

Amazon currently lists the print edition of the book at over $100, and the Kindle edition at over $50. So I can’t in good conscience urge anyone to buy the volume. Urging you to recommend it to your local academic library is another matter, however.

In what follows I address three more specific issues.

Panarchism and Anarchism

Is panarchism a form of anarchism? Certainly it’s often so regarded. De Puydt himself appears to have envisioned a monopoly apparatus administering the various social contracts, but more recent panarchists have generally dispensed with this element; and even de Puydt included “Proudhon’s anarchy” on the list of political options among which citizens could choose (though how the nonexistence of the monopoly apparatus could be one of the options offered by the monopoly apparatus is something of a mystery).

While granting that the distinction may, at least in some cases, be “semantic rather than substantive,” Tucker is inclined to distinguish anarchism from panarchism, for the following reasons. (Incidentally, Tucker takes anarcho-capitalism in particular to accept some notion of territorial sovereignty, which seems to me to be in most cases a misinterpretation.) To begin with, panarchism demands “voluntarism … in the choice of social contracts,” but has “nothing to say about the contents of contracts,” which “may be highly coercive”; thus while anarchists typically reject “states and institutions that are based on authority, hierarchy, domination, and coercion,” panarchy as Tucker conceives it allows people to contract into “states with coercive powers” that “force their citizens to do things they do not want,” and even licenses a “Hobbesian social contract” in which citizens “give up all their civil rights in return for the state’s guarantee of physical safety.” (p. 9)

Judging from this passage, Tucker does not appear to countenance the idea of inalienable rights – that is, rights that cannot be surrendered in contract. But this is not a point on which panarchists are unanimous. Michael Rozeff, in his contribution to the volume, writes that those who “choose a Government” can “choose to leave a Government.”

They need only retain the option to exit in their choice of government. But persons actually cannot give up that option. They cannot voluntarily give up their wills. (p. 91)

De Puydt himself took an intermediate position between complete freedom of exit and irrevocable self-alienation:

I do not suggest one should be free to change one’s government at any time, causing it to go bankrupt. For this sort of contract between states and citizens one must prescribe a minimum term, say one year. (p. 34)

But if one takes the Rozeffian option of complete freedom of exit, then it’s not clear that the anarchist has any reason to reject the legitimacy of contracting oneself into a dictatorship, since a dictatorship that one can leave at any time is merely like bondage using safe words. A slave with a safe word is no slave at all. And the idea of free experimentation with different systems of rules has been embraced by many anarchists, of both communist and market varieties. (On this point, see Kevin Carson’s recent C4SS study Anarchists Without Adjectives: The Origins of a Movement.)

More broadly, for Tucker anarchism and panarchism must be at odds, because panarchism allows people to “associate and dissociate with states voluntarily,” while anarchism “opposes the very existence of states.” (p. 12) For those accustomed to the Weberian definition of the state as a territorial monopoly of force, this might seem puzzling; if the political entities that panarchists advocate are not territorial monopolies, why call them “states,” or suppose that the anarchist rejection of states must apply to them?

Part of the reason, it seems, is that Tucker does not accept the Weberian definition. He writes:

The Greek polis was essentially a structure of people united by law, not by a relation to a territory. When the Greeks colonized, the future state, the polis, its hierarchical political structure, had already existed on the ship, before a favorable precise site was chosen. (p148)

This is a fair point; but I’d want to make two caveats. First, while the Greek polis may not have been a territorial monopoly, it was certainly a monopoly (over a given population); and second, it always ended up in fact claiming and exercising jurisdiction over a particular territory. In both respects it resembles modern states in a way that competing panarchist regimes do not.

In reply, Tucker would presumably point to the “division of power between the church, the king, and the vassals” in medieval Europe, as well as the “extra-territorial arrangements of mixed sovereignty … in the Ottoman and Chinese empires” (p. 149), as examples of (things we call) states that were not monopolies, territorial or otherwise. Again, a fair point; but I would still insist that these states they were much more like territorial monopolies than are the regimes that panarchists propose. People born into a medieval king’s territory often had a choice as to whether to use a royal court, a manorial court, an ecclesiastical court, or a merchant court, but for the most part they had no choice as to whether or not to be subject in general to the king’s authority. The Ottomans allowed Christians to be governed by Christian rather than Muslim law, but this was a grant of privilege from a territorial ruler who determined the content of the concession. And so on.

In short, then, I would resist calling the panarchist’s political regimes “states”; and I have no problem regarding panarchism, at least in its modern form, as a species of anarchism.

Neglected Precursors

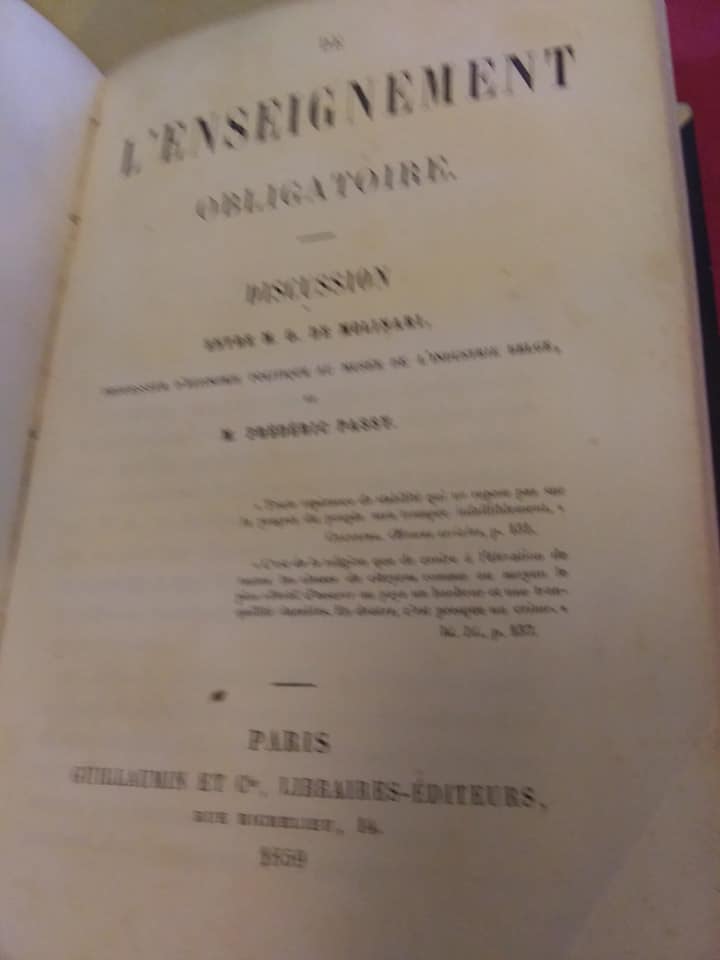

The contributors to the volume identify a number of historical precursors to their ideas. One is de Puydt’s countryman Gustave de Molinari, whose 1849 proposal for competing security agencies is included; another is the anarchist historian Max Nettlau, whose 1909 essay on the subject is also included. Another example, a surprise to me, is Moritz Schlick, the founder of logical positivism. (p. 12) Sadly, his work on the subject – unfinished since, as Tucker rather euphemistically puts it, Schlick “died prematurely” (he was shot by a disgruntled student) – is not included.

There are other precursors that might have been mentioned in the book, but are not. Perhaps the earliest panarchist proposal, albeit made in jest, occurs in Aristophanes’ Acharnians, whose central protagonist, an Athenian citizen, claims the right to decide his own foreign policy, both military and economic, rather than following that of Athens as a whole. A less favorable treatment occurs in Plato’s Republic, in which Athens is described, rather implausibly, as a “supermarket of constitutions” where each citizen can live under whatever regime he likes, regardless of what choice his fellow-ciitzens make. (On panarchist ideas in Aristophanes and Plato, see my recent essay on the subject.)

Another unnoted panarchist precursor is the German idealist Johann Gottlieb Fichte, who defended a right of individual secession in his not-yet-fully-translated 1793 tract Contribution to the Rectification of the Public’s Judgment of the French Revolution. But this is perhaps an unwelcome precursor, given the work’s repulsive – and rhetorically self-defeating – antisemitism. (Rhetorically self-defeating, because Fichte’s ostensible aim in mentioning the Jews is to point to them as a successful example of a non-territorial political community, and so his immediately taking the opportunity to indulge in an antisemitic rant hardly aids his purpose.)

The idea of individual secession was revived independently by Herbert Spencer in his 1850 Social Statics, specifically in his chapter “The Right to Ignore the State” – though while he allows citizens to sever relations with their former state without a change of territory, he does not envision the possibility of their signing up with a competing service provider.

Much closer is the American individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker, who in 1887 wrote:

There are many more than five or six Churches in England, and it frequently happens that members of several of them live in the same house. There are many more than five or six insurance companies in England, and it is by no means uncommon for members of the same family to insure their lives and goods against accident or fire in different companies. Does any harm come of it? Why, then, should there not be a considerable number of defensive associations in England, in which people, even members of the same family, might insure their lives and goods against murderers or thieves?

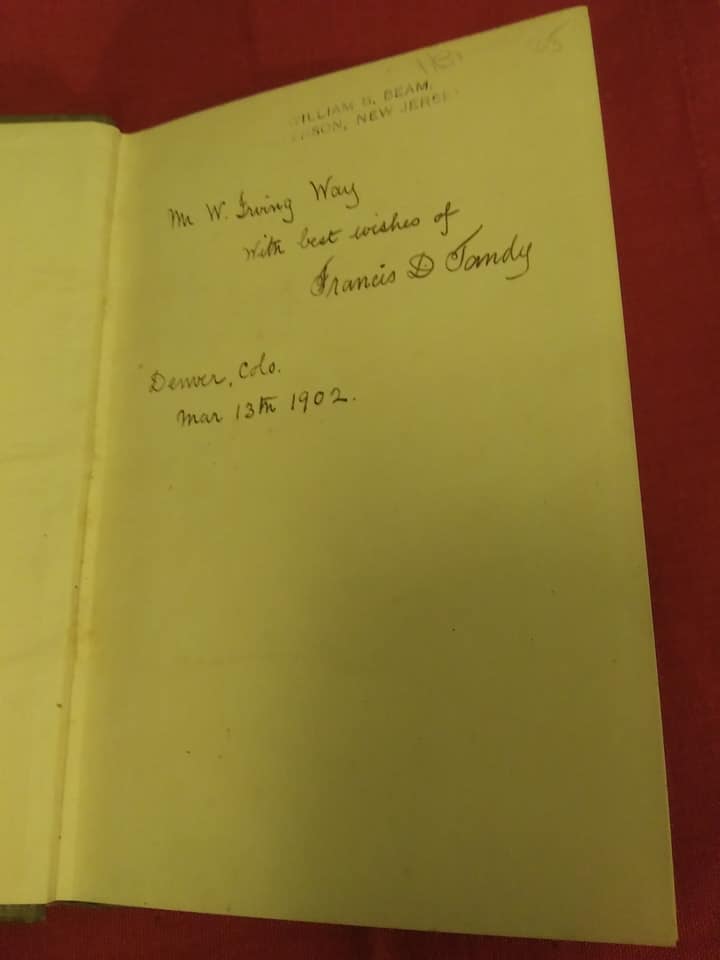

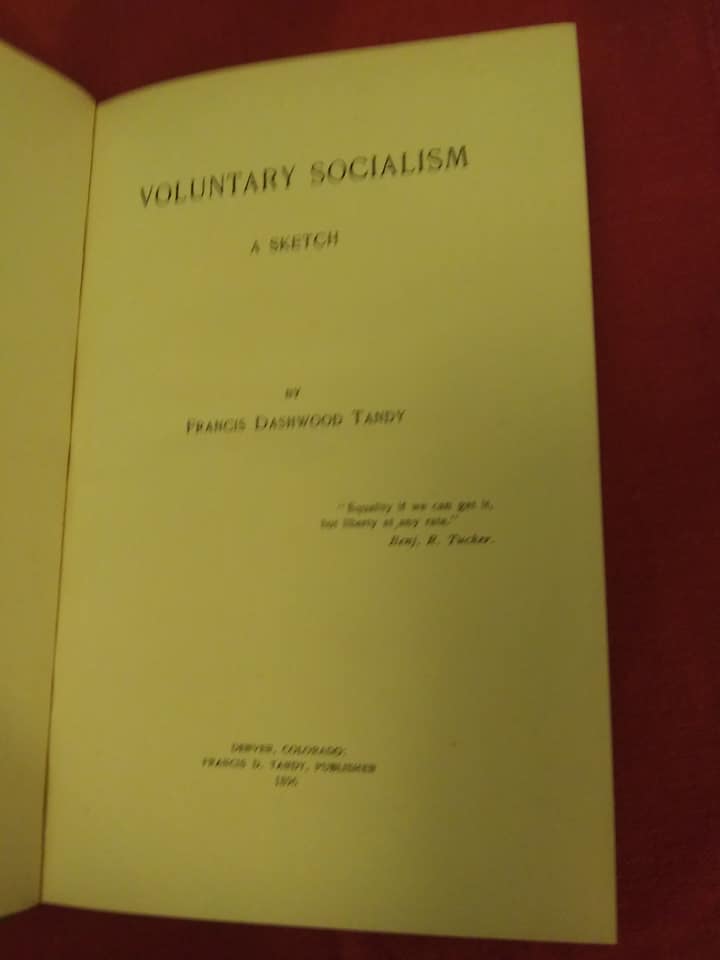

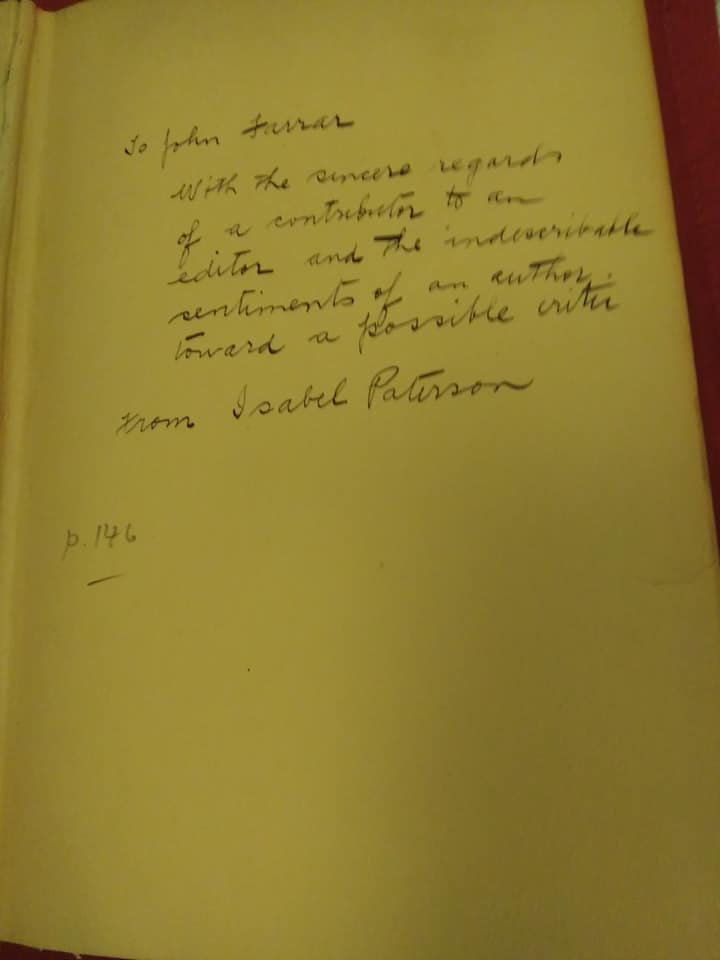

(Tucker incidentally takes the side of Rozeff against his homonym on the question of inalienability, maintaining that “no man can make himself so much a slave as to forfeit the right to issue his own emancipation proclamation.”) Tucker’s disciple Stephen Byington agreed, pointing to the fact that in Kansas City, the state line “runs right through the edge of the city, among popular streets,” so that “[m]en who live on the same street are subject to different laws.” (Byington also mentions the exemptions for Christians in Muslim countries.) Another Tucker disciple, Francis Tandy, held similar views.

Economic Justice

There is one objection to panarchism that I suspect will be widely raised, especially by Rawlsian liberals, and I don’t think it gets much discussion in the book. That objection is that panarchism is economically unfair.

”You want a redistributive state?” Rich Ralph asks Poor Petunia. “Go ahead and sign up for one. But my rich friends and I are all going to sign up for something else. Have fun redistributing wealth among your impoverished pals, but count us out.”

At this point the Rawlsian liberal says: “Look, Ralph: you and your rich friends, and Petunia and her poor friends, have all been part of the same society-wide cooperative endeavor for mutual advantage; they’ve brought you your caviar nachos, you’ve paid their salaries, and so on. We need to ask whether the fruits of that cooperation are being fairly distributed, or whether the situation has been objectionably exploitative. For you to simply pull out and thus declare yourself exempt from the redistributive laws that Petunia and her friends want to pass is rather too much like a thief declaring that he’s going to sign up with a regime that says theft is okay (or at least that theft by members of that regime against members of other regimes is okay) so he’s not bound by the anti-theft laws that his victims want to pass. You can secede from their authority, but they can’t secede from the externalities you’re dumping on them.”

There are a number of different ways that a panarchist could respond to the Rawlsian liberal, but I suspect the most effective would be to show, along the lines that left-libertarians have suggested, that it’s precisely the absence of panarchy (or in other words, the presence of a monopoly state) that is chiefly responsible for the economic disparity with which the Rawlsian is concerned. However, this would require taking sides on issues that at least some panarchists seem to want to remain neutral on, such as the comparative merits of left-libertarian and right-libertarian economic analysis.