[cross-posted at BHL]

Conventional wisdom has it that a) you have a duty to vote, and more specifically that b) at least in winner-take-all two-party electoral systems like the u.s., you have a duty to vote for whichever you regard as the least bad of the two major candidates (as opposed to “throwing away your vote” on a third-party candidate).

According to a contrary argument, one that enjoys some popularity in libertarian circles, c) voting – for anyone – is irrational, since the outcome is overwhelmingly likely to be the same whether you vote or not.

I think all three of these positions are mistaken.

(I’m not going to talk in this post about the argument that voting is immoral; but see my discussions here and here.)

Think first about (c), the argument that voting is irrational. If that argument worked, it would also prove that contributing to a Kickstarter is irrational – at least in cases where the total amount needed to be raised is significantly larger than the amount of one’s contribution. An example would be the Veronica Mars movie project, which raised five million dollars on Kickstarter; the average donation size was reportedly around $60. The odds that an individual’s personal $60 contribution will make the difference to a multi-million-dollar movie’s being made or not is vanishingly small; hence if not making a difference to the outcome is a reason not to vote, it’s also a reason not to contribute to a Kickstarter (except when the amount to be raised is small enough, or the amount one can personally contribute is large enough, that one’s contribution can significantly alter the probability of the project’s being funded).

Yet I suspect that among libertarians sympathetic to argument (c), few will be willing to issue a similar rejection of Kickstarter (or similar services). After all, Kickstarter is a libertarian’s dream; in the words of Reason editor Nick Gillespie, it “allows creators and funders to escape conventional financial, ideological and aesthetic gatekeepers who have long suppressed heterodoxy in media, business, the arts and more.” The ability to evade such gatekeepers is obviously a major benefit to libertarians and other politically heterodox thinkers.

Worse yet, if argument (c) worked against voting, it would also tell against being a libertarian activist as such, since (as noted elsewhere) “no one libertarian activist’s contribution is likely to make the crucial difference as to whether libertarianism triumphs or not.”

The truth is that civilisation depends on people contributing, in thousands of small ways every day, to practices whose maintenance will not stand or fall with any individual such contribution. Thankfully, people contribute to public goods all the time – and do so voluntarily, rational-choice arguments to the contrary notwithstanding. (See, for example, “Covenants With and Without a Sword: Self-Governance Is Possible” by Elinor Ostrom, James Walker, and Roy Gardner.)

And the same is true at an individual level; my success at any personal project depends on my reliably contributing to it over and over, even though success does not depend on any one of those instances, and so each individual contribution can look irrational. But if it were indeed irrational, then it would likewise be irrational to undertake any project that can’t be completed instantaneously – which is absurd.

The crucial fact to recognise is that we have an imperfect duty to contribute to public goods. (For a defense of the claim that we have such a duty, and that it is an imperfect duty, see my article “On Making Small Contributions to Evil.”) An imperfect duty, remember, is not optional or supererogatory; it’s a full-fledged duty. But it’s a duty that can be satisfied by performing the relevant action merely regularly rather than at every opportunity, leaving the agent with a free choice as to the occasions on which she discharges that duty. A duty to contribute to public goods, then, is not a duty to contribute to any and every public good that comes along; one can choose which ones to support.

Suppose I think that of two major political candidates, one of them (say, Hilnald Clump) is a bit less bad than the other (say, Donnary Trinton). Then I might regard a Clump victory as a public good, and might accordingly choose to vote for Clump as one of the instances in which I fulfill my duty to contribute to public goods. Hence the mere fact that the outcome of the election will not be affected by my individual vote does not render voting irrational.

To be sure, this argument does not generate a duty to vote, contrary to position (a). After all, even if one regards a Clump victory as a public good (given the alternative of the even more odious Trinton), the duty to contribute to public goods is an imperfect duty, and one need not choose this particular occasion as one to count toward fulfilling that duty. All the same, the argument does show how voting could be a way of fulfilling a duty, and so does give some aid and comfort to the pro-voting side, supporting a weaker version of position (a).

But it may give less support even to the weaker version of (a) than meets the eye. And in particular it may not give much support to (b). Let’s look closer.

Suppose there’s a third-party candidate – perhaps Gill Stohnson or Jary Jein – whom you regard as less bad than either of the two major candidates, but the third-party candidate has no chance of winning. Is voting for the least bad of the major candidates, rather than for the third-party candidate, the best way of fulfilling your duty?

Not obviously. After all, if you vote the way you’d prefer everyone to vote, as though you were choosing for everyone, then you should choose the third-party candidate. And if someone responds that it’s irrational to act as though you’re choosing for everyone, since in fact everyone else is going to vote however they’re going to vote regardless of what you do, that argument proves too much, since it’s an equally good reason not to vote at all; in fact it’s just the same voting-is-irrational argument (c) over again.

And once one considers what other results one might be contributing to besides someone’s simply getting elected, the case for voting third-party looks even stronger. After all, the larger the margin by which a candidate wins, the more that candidate can get away with claiming a mandate, thus putting him or her in a stronger political position to get favoured policies enacted. So if one thinks that both of the major candidates would do more harm than good if elected (even if one is worse than the other), then making the winning candidate’s totals smaller becomes a public good to which one might choose to contribute – perhaps by voting for a third-party candidate (though also, perhaps, by voting for whichever of the major candidates one thinks is most likely to lose).

Moreover, if you think that higher vote totals for a third-party candidate are a good thing even if that candidate doesn’t win (e.g., by garnering more publicity for alternative candidates and thus helping to build future support for a political movement you favour, sending a message of disenchantment with the political establishment, etc.), then voting for that candidate contributes to a public good other than just that candidate’s getting elected. Plus your total percentage contribution to the desired end will be greater, both because the number of voters you’re cooperating with will be smaller and because the result is incremental rather than all-or-nothing. All other things being equal, it seems plausible that the case for contributing to a public good gets stronger as the degree of impact of that contribution increases.

So whatever pro-voting case can be extracted from my argument seems more favorable to voting for third-party candidates (when they’re better than the major candidates) than to voting for a major candidate. There seems to be no strong case for position (b).

But in fact the case for voting third-party is not all that strong either; indeed, the problems with (b) turn out to be problems for (a) as well. Suppose your favoured third-party candidate, while better than either of the two major candidates, is still fairly lousy (in your view). Then the message you’re sending, and the cause you’re supporting, are a muddled mixture of good and bad. You might well contribute more effectively and unambiguously to the public good you seek by writing a clear and compelling op-ed or blog post rather than voting for a mixed-bag candidate.

Finally, suppose you’re an anarchist (as you should be). Trying to achieve anarchy via the route of electoral politics seems a lot less promising strategically than the agorist approach of building alternative institutions and trying to win people’s affiliation to those institutions and away from the state; the former requires convincing 51% of the electorate in order to accomplish anything, while the latter makes room for incremental success at the margin. Moreover, just as high vote totals for the winning candidate will be interpreted as a mandate for that candidate, so high vote totals in general will be regarded as a mandate for the system – whereas what we as anarchists should be seeking to do is to deligitimise the system.

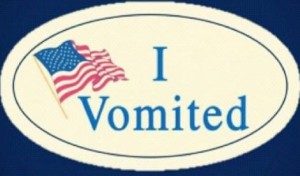

In the light of those considerations, refraining from voting, thereby doing one’s part to deemphasise the importance of electoral politics in the wider culture, starts to looks like a better contribution to a public good than voting does.

And that’s why I’ll be boycotting the vote this Tuesday.