[cross-posted at POT]

[T]here were double meanings in

the Necronomicon of the mad Arab

Abdul Alhazred which the initiated

might read as they chose ….

Sometimes two terms can be the same in reference but different in sense, like “the morning star” and “the evening star,” or “Mark Twain” and “Samuel Clemens,” or … “John Galt” and “Cthulhu.”

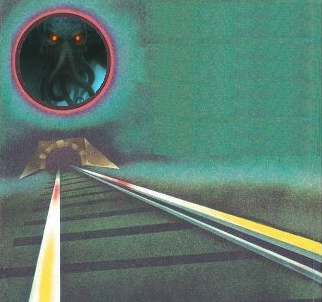

Yes, think about it. Galt and Cthulhu – or Galthulhu, if you will – are both hidden, mysterious figures who act in secret, biding their time until they can reclaim the world for themselves and their kind.

Galthulhu’s hiding place is described, in the Dark Gospel of Rand, as a “radiant island in the Western Ocean” that he discovered while “fighting the worst storm ever wreaked upon the world”:

He saw it in the depth, where it had sunk to escape the reach of men. He saw the towers of Atlantis shining on the bottom of the ocean. It was a sight of such kind that when one had seen it, one could no longer wish to look at the rest of the earth. John Galt sank his ship and went down with his entire crew.

But Galthulhu did not die, since, as per the Dark Gospel of Lovecraft –

That is not dead which can eternal lie,

And with strange aeons even death may die

– or, as the Dark Gospel of Rand reports the creature’s own words: “Of course I am all right, Professor. I had to be. A is A.” Instead, Galthulhu waits in expectant dormancy in its sunken city, as the Dark Gospel of Lovecraft explains:

In the elder time chosen men had talked with the entombed Old Ones in dreams, but then something had happened. The great stone city R’lyeh, with its monoliths and sepulchres, had sunk beneath the waves; and the deep waters, full of the one primal mystery through which not even thought can pass, had cut off the spectral intercourse. But memory never died, and high-priests said that the city would rise again when the stars were right. … Cthulhu still lives, too, I suppose, again in that chasm of stone which has shielded him since the sun was young. His accursed city is sunken once more, for the Vigilant sailed over the spot after the April storm; but his ministers on earth still bellow and prance and slay around idol-capped monoliths in lonely places.

And in what sort of buildings do Galthulhu and his acolytes live? According to Lovecraft, in “greenish stone blocks” with “crazily elusive angles of carven rock” whose geometry is “abnormal, non-Euclidean, and loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours.”

Similarly, Galthulhu’s forerunner, according to Rand, designs buildings that “looked like a lot of boxes piled together without rhyme or reason,” such as “a rising mass of rock crystal” with a “severe, mathematical order holding together a free, fantastic growth; straight lines and clean angles, space slashed with a knife … an incredible variety of shapes,” like “a symphony played by an inexhaustible imagination, and one could still hear the laughter of the force that had been let loose on them, as if that force had run, unrestrained, challenging itself to be spent, but had never reached its end.”

And the preferred colour of Galthulhu’s structures? – “shining metal” with an “odd tinge” of “greenish-blue.”

As the hour of Galthulhu’s resurrection approaches, the creature’s ability to influence human thoughts returns, and the “monstrous menace” begins, in Lovecraft’s terms, “its siege of mankind’s soul,” by “sending out at last, after cycles incalculable, the thoughts that spread fear to the dreams of the sensitive and called imperiously to the faithful to come on a pilgrimage of liberation and restoration” – i.e., it begins, as Rand describes, “draining the brains of the world.”

“That cult would never die till the stars came right again,” Lovecraft explains, “and the secret priests would take great Cthulhu from His tomb to revive His subjects and resume His rule of earth.” What Lovecraft describes as future, Rand describes as past: “We are going back to the world,” she has Galthulhu say, as the creature “raised his hand and over the desolate earth he traced in space the sign of the dollar.”

In the meantime, the creature’s name has become part of a popular chant expressing the despair of the damned, whether as “Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn!” or as “Who is John Galt?”

What does Galthulhu offer to its followers? Freedom and egoistic indulgence, according to Rand:

Such was the service we had given you and were glad and willing to give. What did we ask in return? Nothing but freedom. …

It’s selfish, heartless, ruthless! It’s the most vicious speech ever made! It … it will make people demand to be happy!

Or in Lovecraft’s words:

The time would be easy to know, for then mankind would have become as the Great Old Ones; free and wild and beyond good and evil, with laws and morals thrown aside and all men shouting and killing and revelling in joy. Then the liberated Old Ones would teach them new ways to shout and kill and revel and enjoy themselves, and all the earth would flame with a holocaust of ecstasy and freedom. Meanwhile the cult, by appropriate rites, must keep alive the memory of those ancient ways and shadow forth the prophecy of their return.

And then there will be only the ocean and the sky and the figure of Howard Phillips Lovecraft.