One song about the problems with living on earth, and another song with a recipe for addressing them ….

229. Devo, “Planet Earth” (1980):

230. Leslie Fish, “Black Powder and Alcohol” (1989):

One song about the problems with living on earth, and another song with a recipe for addressing them ….

229. Devo, “Planet Earth” (1980):

230. Leslie Fish, “Black Powder and Alcohol” (1989):

[cross-posted at POT]

(English lyrics to the third song here.)

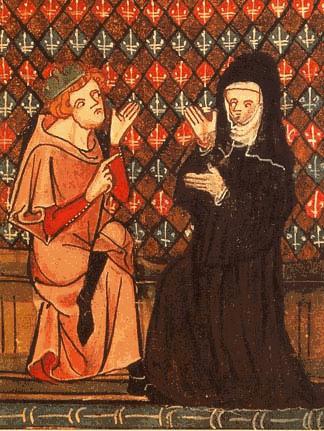

What is courtly love? As will soon become apparent, there’s no description that’s uncontroversial; but perhaps the following won’t be too objectionable as at least a first pass:

(On the odd attempt to synthesise Ovid with Neoplatonism: the mediævals by and large had an enormous enthusiasm for anything coming down to them from antiquity, regarding it as a repository of precious wisdom, and so had a mania for attempting to reconcile all of it so far as possible – Plato with Aristotle, both with the Bible, and so on.)

[This post began life as notes for students in my mediæval philosophy course. One of them will be glad to learn that courtly love also displayed characteristics of what he calls “meta-normalization.” Christine de Pizan (late 14th-early 15th c.) has one of her courtly heroes describe his experience this way:

It is astonishing how Love was able to take my heart away by means of her whom I’d seen a hundred times before but had never, in all my young life, thought about before. … I often used to see her for long periods of time but, except for that day, I had paid no attention. … For at that moment … her conversation and her sweet and gentle bearing pleased me more than ever before, and I was struck dumb. I looked at her with desire, studying her beauty, for she seemed more especially beautiful now than ever before, and possessed of much more elegance and far greater sweetness. Then Love, the playful archer … took up his bow [and] pierced my heart through. Them I was bewildered! … But my heart consented to Love’s wound. It did not bring death – rather, with that puncture my adventure began. … And so my earliest youth came to an end. At that moment True Love taught me to live differently; that was the hour of my capture. … Then Love – just to make my tender heart burn the more – caused me to receive a sweet look from her as she came to see me off. For, in leaving, I turned my gaze upon her face; as I turned, she shot at me a gentle, delicious spark from her fair and loving eyes in such a way that the love that entered me has never left.

— Christine de Pizan, Book of the Duke of True Lovers]

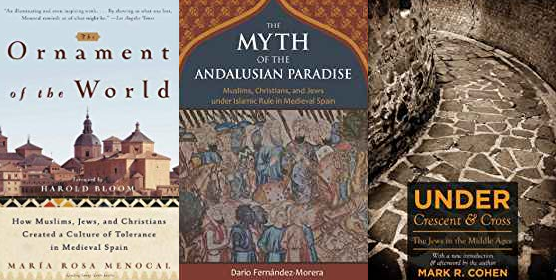

But what was courtly love more specifically, and how did it arise? Here there is much disagreement.

What Is This Thing Called Love?

Nathaniel Branden, in his Psychology of Romantic Love, presents a view that used to be fairly typical. (Although I’m going to be criticising most of what he says, I pick him not to pick on him, but rather because Branden is likely to be of interest to many of my readers for other reasons – talking about blog readers now, not my students. Trying to serve two audiences here, though I’m not sure which one is God and which one is Mammon.)

For Branden, courtly love represents a crucial step in the development toward “our” modern conception of romantic love. “Economics, not love,” Branden tells us, “was the motivating force for union in primitive societies …. So far as we can ascertain, in primitive cultures the idea of romantic love did not exist at all.” In support of this claim, Branden cites the example of an “anthropologist who lived among the Bemba of Northern Rhodesia in the 1930s,” who

related to a group of them an English folk-fable about a young prince who climbed glass mountains, crossed chasms, and fought dragons, all to obtain the hand of a maiden he loved. The Bemba were plainly bewildered, but remained silent. Finally an old chief spoke up, voicing the feelings of all present in the simplest of questions: “Why not take another girl?” he asked.

Matters improved during the Greco-Roman period, Branden tells us, but still fell short:

Despite the fact that much of Greek culture reflects a worship of physical beauty, clearly evident in attitudes toward sex and love was the view that a person was made of two disparate elements: flesh, which pertained to one’s “’lower” nature, and spirit, which pertained to one’s “higher.” … The Greeks idolized the spiritual, not the carnal, relationship between lovers, and for the Greeks, this profound, spiritually significant love was possible only in the context of homosexual relationships, usually between older men and younger boys. …

While sexual desire apart from deeper feeling was often regarded as effeminate and unhealthy, a passionate love relationship between two men was idealized as a relationship in which the older lover inspired the younger to nobility and virtue, and the love between them elevated the mind and the emotions of both.

On the other hand, antifeminism was a pronounced theme in the culture of classical Greece, and although the Greeks were scarcely indifferent to heterosexual sex or to female beauty, they viewed their interest as being devoid of ethical meaning or spiritual significance. …

Except in its ideal sense as an elevating admiration, which could exist only among men, “love” was predominately [sic] viewed as a pleasurable, enjoyable game, an amusement, a diversion, of no deep importance or lasting significance. Passionate sexual love, when it appeared, was commonly regarded as a tragic madness, an affliction that took possession of a man and carried him away from that calm, cool evenness of disposition so much admired by the Greeks. The notion of “marrying for love” was consequently as absent from the thinking of the Greeks as it was from the thinking of primitive man. …

Women in Rome gained significantly in legal status and enjoyed a far greater measure of freedom, economic independence, and cultural respect than they had known previously. They were more likely, then, to be in a position of equality in a love relationship. … Roman epitaphs, letters between husbands and wives, and occasional references by contemporary social observers evidence the strength of the marital bond and the existence of long, harmonious, even affectionate, unions between some partners. But passion remained very foreign to their view of marriage.

At the height of the Roman empire, and through the period of its disintegration, both men and women sought the experience of passion, the excitement and glamour of sexual relationships in extramarital adventures and affairs of the sort made famous by the poet Ovid’s Ars Amatoria. At the height of the empire, adultery on the part of both sexes was widespread and virtually taken for granted as a sport necessary to relieve the tedium of existence; the aristocrats of Rome indulged in the jaded, frenetic sensuality that we associate with Roman decadence: a vicious mixture of love and hatred, attraction and revulsion, desire and hostility.

And then after the Greco-Roman period comes what Branden sees as the disaster of Christianity, with its otherworldly, anti-bodily views, including the idea (from St. Jerome) that “for a man to love his wife too ardently is a sin worse than adultery.”

Let’s pause here for a moment.

I don’t know what may or may not have been true among the Bemba specifically, but an intense attachment to a particular romantic partner is not exactly unknown in tribal societies. As the 19th-century sociologist Edvard Westermarck notes in his History of Human Marriage (in a rather racist tone, though making an antiracist point):

Among the Indians of Western Washington and Northwestern Oregon, says Dr. Gibbs, “a strong sensual attachment undoubtedly often exists, which leads to marriage, as instances are not rare of young women destroying themselves on the death of a lover.” The like is said of other Indian tribes, in which suicide from unsuccessful love has sometimes occurred even among men. Colonel Dalton represents the Paharia lads and lasses as forming very romantic attachments; “if separated only for an hour,” he says, “they are miserable.” Davis tells us of a negro who, after vain attempts to redeem his sweetheart from slavery, became a slave himself rather than be separated from her. In Tahiti, unsuccessful suitors have been known to commit suicide; and even the rude Australian girl sings in a strain of romantic affliction – “I never shall see my darling again.”

Branden’s assumption that romantic love was initially the province of the courtly mediæval elite and was of no concern to the average person does seem to have been shared by some of the proponents of courtly love themselves. In his Art of Courtly Love, Andreas Capellanus notes:

[I]t rarely happens that we find farmers serving in Love’s court, but naturally, like a horse or a mule, they give themselves up to the work of Venus, as nature’s urging teaches them to do. … And even if it should happen at times, though rarely, that contrary to their nature they are stirred up by Cupid’s arrows, it is not expedient that they should be instructed in the theory of love, lest while they are devoting themselves to conduct which is not natural to them the kindly farms which are usually made fruitful by their efforts may through lack of cultivation prove useless to us.

Explanatory note: the mediævals generally distinguished between Venus/Aphrodite, the goddess of sexual intercourse and/or the desire for same, and her son, Cupid/Amor/Eros/Love, the god of a love that has a sexual element but is not purely sexual. When the mediævals speak of love as being ennobling to the lover, focused on a single beloved, etc., it is the love associated with Cupid/Eros/Amor that they have mind – though when such a love is consummated, then Venus is involved as well. So Andreas’s claim is that farmers pursue sex (“the work of Venus”) in a way that is animal-like, because their sexual desires are not ordinarily embedded in a context of genuine love (“Love’s court,” “Cupid’s arrows”) – and just as well, since the farmer’s proper job is to focus on providing the material wherewithal necessary for the elite to pursue their amorous pastimes. (I believe the technical Scholastic term for what Andreas is doing here is “cruisin’ for a bruisin’.”)

As for Branden’s claim that passion in marriage is a recent invention, a Sumerian love poem written over 4000 years ago, from a bride to her prospective bridegroom, does not strike me as devoid of passion:

Bridegroom, I would be taken by you to the bedchamber,

You have captivated me, let me stand tremblingly before you. …

Bridegroom, let me caress you,

My precious caress is more savoury than honey,

In the bedchamber, honey-filled,

Let me enjoy your goodly beauty

(Even if, as many scholars think, the wedding referred to is only a symbolic one between a human king and a fertility goddess, it makes sense as a metaphor only if it also makes sense literally.)

With regard to the Greeks, the status of homosexual relationships in ancient Greece is such a complex thicket that I’m not going to get into it, except to say that easy generalisations are treacherous here. (It also seems a bit homophobic to treat a tradition that exalts heterosexual relationships while devaluing homosexual ones as healthier than a tradition that exalts homosexual relationships while devaluing heterosexual ones, as Branden seems to be doing here.) But in any case, contrary to what Branden suggests, romance narratives in which the hero and heroine, passionately in love with each other, go through many perilous adventures in order to be finally (and maritally) reunited, were a regular product of ancient Greek culture, as for example Anthia and Habrocomes by Xenophon of Ephesus; Leucippe and Cleitophon by Achilles Tatios; Chaereas and Callirhoe by Chariton of Aphrodisias; Daphnis and Chloë by Longos; and Theagenes and Chariclea by Heliodorus of Emesa. (These are all usefully collected in B. P. Reardon’s excellent anthology Collected Ancient Greek Novels – though I cannot agree with Reardon’s claim that these works represent the earliest European novels. Surely The Education of Cyrus by Xenophon [of Athens, not Ephesus] takes precedence here.) The myth of Hero and Leander also features a passionate (albeit doomed) heterosexual love relationship. Branden seems to be drawing his conclusions from a one-sided diet of examples.

Branden continues:

Given the brutally inhuman sexual repressiveness of the Middle Ages and the strict regulation of marriage by the church, it is not astonishing that the first blind groping toward a better view of the man/woman relationship should emerge in the form of a strange concoction of beliefs about love and marriage known as the “doctrine of courtly love.” Originating in the south of France in the eleventh century, the doctrine of courtly love was developed by troubadours and poets in the courts of the nobility – courts often ruled by the wives of nobles gone off to the Crusades.

The doctrine upheld as an ideal an exalted passion between a man and a woman; not between a man and his wife, but between a man and someone else’s wife. Love, this time in a passionate and spiritual sense, was identified specifically with extramarital involvements. Courtly love thus maintained the dismal view of marriage that had been accepted for hundreds of years. There is considerable controversy over the extent to which courtly love was an actual, or mainly a literary, phenomenon, but the fact that it is recorded signifies that it was a concept in the medieval mind. …

A “code of love” proclaimed by the countess of Champagne in 1174 …. declares [that] “love cannot extend its powers over two married persons; for lovers must grant everything, mutually and gratuitously the one to the other without being constrained thereunto by any motive of necessity” ….

Despite its many naivetés, contained within the doctrine of courtly love as an expressed ideal are three principles relative to the concept of romantic love as we understand it today: Authentic love between a man and a woman rests on and requires the free choice of each and cannot flourish in the context of submission to family or social or religious authority; such love is based on admiration and mutual regard; and love is no idle diversion but is of great importance to one’s life. In these respects, historians are justified in regarding the doctrine of courtly love as marking the beginning of the modern concept of romantic love.

But courtly love falls far below any mature understanding of romantic love, not only due to the magnitude of its psychological unrealism … but by its utter failure to integrate love and sex in any concrete manner. Courtly love was idealized to the extent that it remained unconsummated. The value of the love relationship was justified by the ennoblement of the lover, who was motivated to perform virtuous and courageous acts to win the love of his ideal …. Unfulfilled and unsatisfied desire fueled the striving and the passion; few relationships were portrayed as surviving consummation. The affairs of the most famous of the courtly lovers, Lancelot and Guinevere, and Tristan and Isolde, ended in consummation – and in guilt and despair. This was not a vision of love appropriate to men and women who wish to live on earth.

Hence, for Branden, the fullest realisation of romantic love had to await “[t]he rise of commerce and the development of an emerging middle class … accompanied by a new awakening to the possibilities and values of earthly existence.”

To Love Pure and Chaste From Afar

Two of Branden’s central claims here are that courtly love is essentially a) adulterous, and b) either unconsummated or doomed. But here once again we seem to have the problem of a one-sided diet of examples. (Three months ago, prior to the fuller research, reading and re-reading, that I’ve done since, I was peddling the same false notions – though even then, I’m happy to say, I was noting exceptions.) Some courtly-love narratives featured adulterous relationships, some didn’t; some were consummated, some weren’t; of those that were adulterous and consummated, some ended tragically and some did not. Moreover, adultery was presented sometimes with approval and sometimes with disapproval. There simply is no one model that all the stories fit.

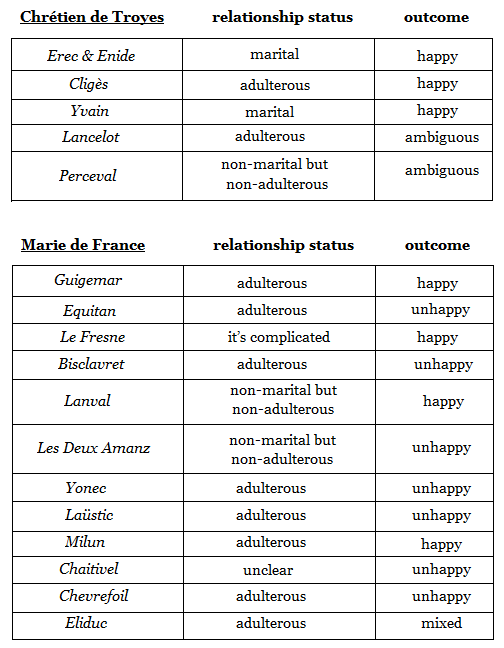

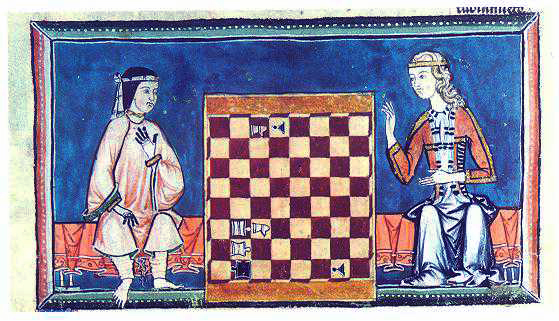

Consider this chart of what happens in the romances of two of the most important courtly-love authors, Chrétien de Troyes and Marie de France:

(The reason I describe the status of the relatonship in Le Fresne as “complicated” is as follows: the lovers begin with a non-adulterous, non-marital (but consummated) affair; the male lover is then pressured into abandoning his beloved and marrying someone else; the marriage lasts only a day, being immediately annulled and never consummated, whereafter the lover marries his original beloved. So the lover’s love for his beloved is indeed adulterous, but only for one day.)

As for Tristan and Isolde, not all versions of that adulterous, consummated romance end unhappily. As I’ve discussed recently, there’s one Welsh manuscript tradition, the Ystoria Trystan, where the story instead ends like this:

Then Arthur made peace between Trystan [= Esyllt’s lover] and March [= Esyllt’s husband] … and Arthur spoke with them both in turn; and neither of them consented to be without Esyllt. Then Arthur judged her to the one while the leaves were on the wood, and to the other while the leaves were not on the wood, and to her husband to make the choice. He chose the time when the leaves were not on the wood, because at that season the nights would be longer. Arthur announced that unto Essylt, and she said: “Blessed is the judgment and he who gave it” ; and sang this stave:

Three trees have a happy way:

Holly, ivy, yew are they;

Green they keep their leaves alway,

Trystan’s am I then for aye.In this way March, son of Meirchion, lost his wife for ever.

(Excerpted in Roger Sherman Loomis’s translation of Thomas of Britain’s Romance of Tristram and Ysolt)

The preference expressed for unconsummated over consummated relationships in Andreas Capellanus’s Art of Courtly Love, often cited as a source of the doctrine, is actually fairly weak and perfunctory. Andreas writes:

[O]ne kind of love is pure, and one is called mixed. It is the pure love which binds together the hearts of two lovers with every feeling of delight. This kind consists in the contemplation of the mind and the affection of the heart; it goes as far as the kiss and the embrace and the modest contact with the nude lover, omitting the final solace, for that is not permitted to those who wish to love purely. … This love is distinguished by being of such virtue that from it arises all excellence of character, and no injury comes from it, and God sees very little offense in it. … But that is called mixed love which gets its effect from every delight of the flesh and culminates in the final act of Venus. … [T]his kind quickly fails, and lasts but a short time, and one often regrets having practiced it; by it one’s neighbor is injured, the Heavenly King is offended, and from it come very grave dangers. But I do not say this as though I meant to condemn mixed love, I merely wish to show which of the two is preferable. But mixed love, too, is real love, and it is praiseworthy, and we say that it is the source of all good things, although from it grave dangers threaten, too. Therefore I approve of both pure love and mixed love, but I prefer to practice pure love.

Incidentally, notice also that for Andreas, unconsummated love is still pretty carnal, as it permits “modest contact with the nude lover,” omitting only the “final solace” of actual intercourse. By contrast with mixed (i.e., consummated) love, whereby “one’s neighbor [presumably the husband] is injured,” in the case of pure love “no injury comes from it, and God sees very little offense in it.”

Likewise Sir Gawain, in the 14th-century romance Gawain and the Green Knight, who as a guest of a noble lord is visited by the lord’s flirtatious wife (admittedly not naked, but apparently rather scantily clad at any rate) while he is in his bed, accepts her kisses and embraces there; but because he does not actually have sex with her, he is counted as not having departed from virtue in that respect. Or again in Chrétien de Troyes’s Perceval, the hero and heroine spend the night in bed together, “side by side with lips touching all night long,” apparently without further consummation (though in this case the heroine is unmarried). In Marie de France’s Yonec, too, the lovers share a bed, though they do not touch. (Compare the widespread courtship custom, in 18th-century America, of “bundling,” in which unmarried sweethearts would spend the night together in bed, albeit fully clothed.) Andreas’s conception of pure love is not terribly pure by traditional Christian standards; as Thomas Aquinas writes:

A lustful look is less than a touch, a caress or a kiss. But according to Matthew 5:28, “Whosoever shall look on a woman to lust after her hath already committed adultery with her in his heart.” Much more therefore are lustful kisses and other like things mortal sins.

(IIaIIæ 154.4)

In any case, Andreas’s (rather perfunctory) preference for pure over mixed love was not universally shared, as I’ve noted. To take one example: the 13th-century author Jean de Meun’s reaction, in The Romance of the Rose, to the classical Greek story of Aphrodite and Ares being trapped in their adulterous embrace by Aphrodite’s jealous husband Hephaestus, with a finely woven net as strong as bronze but as invisible as a spiderweb, was not “such are the wages of sin,” but rather: if only Aphrodite and Ares had had the advantage of modern technology, namely 13th-century magnifying glasses, they could have detected the trap and avoided it, continuing their liaison without disturbance.

The idea that courtly love represents a rebellion against the church also fails to reckon with the fact that a number of the proponents of such love, most notably Andreas Capellanus [“André the Chaplain”] himself, were themselves men of the church – though admittedly churchmen attached to royal courts, during the period when such posts were filled by royal rather than by ecclesiastical decision (on this see Jaeger below).

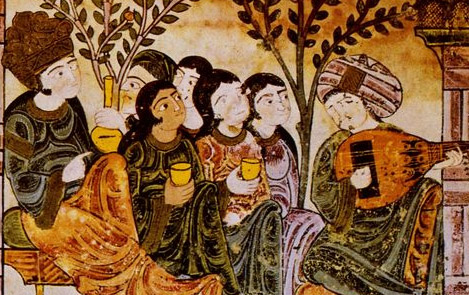

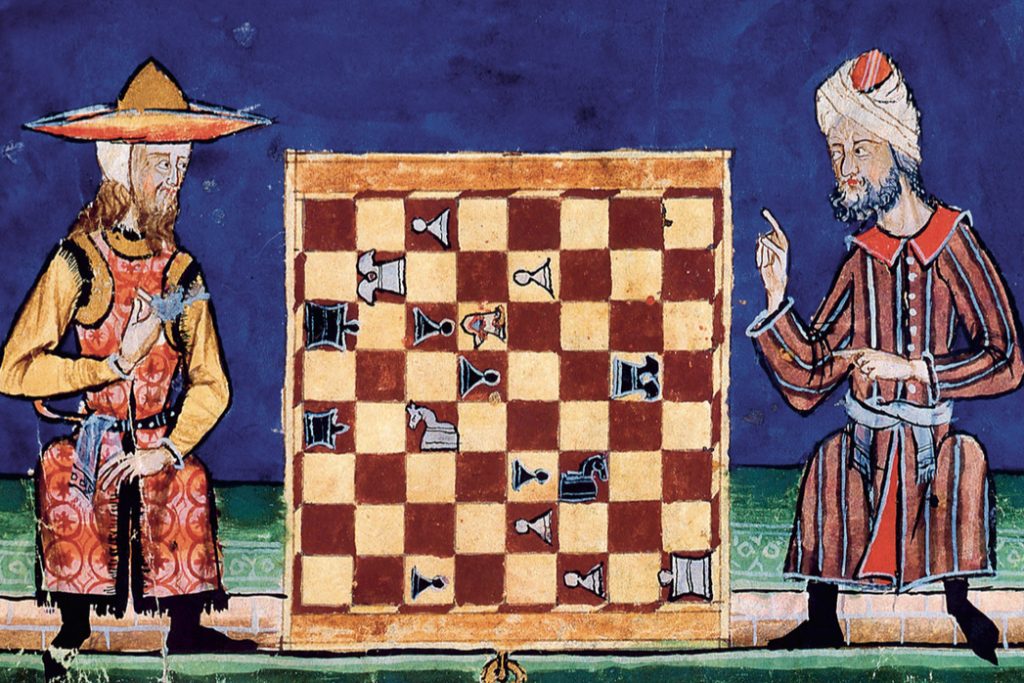

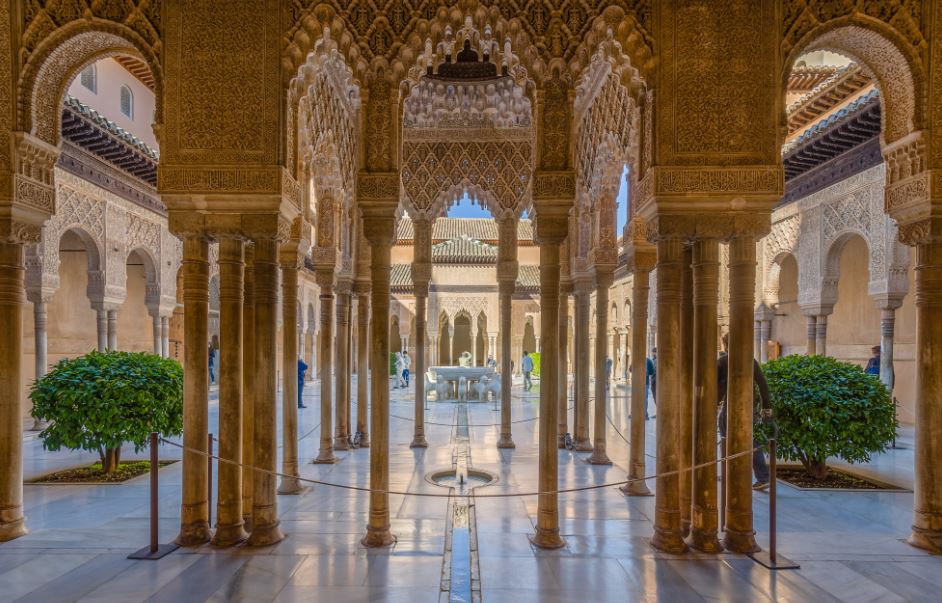

Consider also the Islamic (Andalusian) antecedents of the courtly-love tradition. Certainly the Andalusian material draws on Platonic ideas of spiritual love; for example, Ibn Hazm, in The Dove’s Neck-Ring, defines love as

a reunion of parts of the souls, separated in this creation … and so one kind zealously yearns for one of its kind …. Thus it is proved true that love is a spiritual approval and a mutual commingling of souls ….

And Ibn Hazm cites Ibn Dawud’s similar suggestion, in his Book of the Flower, that

God … created each spirit in a round shape, like a sphere, and then cut it also. Then he placed into each body one half of this sphere. And so when a body meets another into which the other half of the spirit (cut from the same sphere) was placed, there arises between them passionate love, on account of their former relationship.

(Here Ibn Hazm and Ibn Dawud both seem to be conflating Aristophanes’ speech in Plato’s Symposium with the later, more ethereal vision presented by Diotima’s speech in the same work, thus producing a rather more spiritualized thesis than what Aristophanes actually describes.)

But for the Arab poets of al-Andalus, love relationships were generally depicted as having both a carnal and a spiritual aspect; and while in some cases they were depicted as unconsummated, in other cases the reverse was true. Moreover, despite, e.g., Ibn Hazm’s protestations to the contrary, the consummated relationships were in many cases depicted as adulterous also. The following poem, for example, is reasonably unambiguous:

My darling, make up your mind. Arise! Hurry and

kiss my mouth. Come embrace

my breast and raise my anklets to my earrings. My

husband is busy.

(In Leslie F. Compton, ed., Andalusian Lyrical Poetry and Old Spanish Love Songs: The Muwashshah and Its Kharja)

Ibn Hazm is fairly relaxed about homoerotic content, but scandalised by adulterous content; for his Christian counterparts it was generally the other way around – although homoerotic poetry was hardly unknown in the Christian world, as for example:

Beautiful boy, with the beauty of flowers,

My glittering jewel, I would like you to know

That the radiance of your visage

Was for me a touch of love ….Even the Ruler of the gods above

Was once a kidnapper of young men;

If he were here, he would surely snatch

Your beautiful form to his heavenly bed.In his great palace up on high,

You could render him double duty:

At night in bed, pouring drinks by day

You could wholly please our great Jove.

(Hilarius Anglicus, 12th century; in James J. Wilhelm, ed., Lyrics of the Middle Ages: An Anthology)]

It’s also frequently said (admittedly not by Branden, but by many others) that the beloved in the troubadours’ songs is always cold and haughty, forever resisting the lover’s entreaties and leaving him to suffer (as in the first two songs posted above, “Douce Dame Jolie” and “Greensleeves”). Again, a one-sided diet of examples. Consider this dialogue-song, “Rosa Fresca Aulentissima,” by the 13th c. Sicilian troubadour-poet Cielo d’Alcamo:

(The video only has the first verse.) Here are some of the lyrics (the translation [not mine!] is rather uninspired, but you’ll get the idea):

— Fresh, sweet rose, my summer sprout …

I’m in hellish fire. Pluck me out!

Lady, I know no peace night or day

Because my thoughts all turn your way. …

You give me pleasure constantly.

Why not place our love in unity? …

Who wants to be a lonely quarry?

Don’t resist, dear. You’ll be sorry.— Me be sorry? Why I’d rather be slain ….

Why’d you prowl around here half-insane?

Go home, troubadour. Sit.

I don’t like your talk one little bit ….— Oh me! It’s not the first time I’ve felt the lash. …

No other girl ever made me act as rash

As you do, my envied rose sublime;

I still think that Fate will make you mine.— If that’s my fate I’ll leap off a cliff

Rather than waste my beauty in your hands.

I’ll cut my hair, if that’s destiny’s drift

And really become a nun

Before I’d let you have your little fun ….

If you don’t get up and go home to bed

I’d be very happy to see you dead ….

(In Wilhelm, Lyrics of the Middle Ages)

Cielo’s song, and other troubadourial dialogue-songs like it, incidentally seem like forerunners of this famous Elvis/Ann-Margret duet:

But anyway, my point, and I do have one, is: sometimes these troubadourial dialogue-songs end with the beloved’s perpetual refusal – but “Rosa Fresca Aulentissima” actually doesn’t. After lengthy entreaties the woman is eventually won over, and her final lines are:

Suddenly my body’s setting me on fire.

I wronged you, but – mercy! I surrender.

Now quick! Upstairs let’s turn and bend

And give this long, long talk a happy end.

The notion that the courtly lover’s affections are always either unrequited, or requited but impeded by circumstance, is difficult to sustain.

Thus Glyn Burgess and Keith Busby, in the introduction to their edition of the lais of Marie de France, warn against the “dangers inherent in generalizing” in approaching the literature of courtly love:

Some poems do have a timorous lover standing in fear of his lady, but the majority do not; some … relationships are adulterous, but others are not. In retrospect, it seems difficult to conceive why [the courtly-love stereotype] ever gained such general acceptance, unless it be that most readers of medieval literature read nothing but the stories of Lancelot and Guinevere and Tristan and Iseult. Classic as these stories may be … they are not in all respects typical of the kind of love-relationships portrayed in medieval literature. Love in medieval literature, as in any other period … is too complex to be reduced to a single model ….

The standard generalisations about courtly love have so many exceptions that many scholars have simply thrown their hands up and denied the existence of any such thing, dismissing both the term “courtly love” and the phenomenon it purports to refer to as inventions of 19th-century scholarship. But this is surely too quick. The term “courteous love” (cortez amors) does show up in at least one mediæval text; true, the standard mediæval term was “noble love” or “refined love” (fin’ amor), but that’s clearly in the same ballpark. And while Andreas Capellanus’s treatise on love did not have as its original title The Art of Courtly Love (which is an intrusion by the translators), but rather reads in most mediæval manuscripts as either De Amore (“On Love”), De Arte Amandi (“On the Art of Loving”), or De Arte Honeste Amandi (“On the Art of Loving Nobly”), there is one manuscript tradition where the title is Liber Amoris et Curtesie (“Book of Love and Courtesy/Courtliness”), which is a near miss at worst. In any case, there was undeniably an ethic of what the mediævals regularly called “courtliness” or “courtesy” (courtoisie, curialitas), originally a code of manners appropriate to members of a royal or aristocratic court, that included ideas about loving honeste (“nobly”), sapienter (“wisely”), and/or civiliter (“urbanely,” “in a civilised manner”), and if there were strong disagreements about the details, there’s still a recognisable sense in which various divergent texts were part of the same conversation. As Stephen Jaeger writes in Ennobling Love (about which more below): “Courtly love was not a doctrine, but a large grid crisscrossed by conflicting opinions.”

They’ll Tell You Wicked Loving Lies

Many scholars have seen courtly love, with its exaltation of women and its insistence on their right to choose their romantic partners, as an early adumbration of feminism – accordingly hailing or reviling it, as their further commitments have inclined. Today, some alt-right and men’s-rights-movement websites (which I haven’t linked to, because they’re kind of creepy) even seem to regard the courtly-love tradition as the root of all the feminist evils allegedly besetting modern society.

By contrast, feminists have often looked at courtly love with a more jaundiced eye, from Christine de Pizan in the 15th century, who raised a sharp critique of the inherent misogyny in The Romance of the Rose, to Sarah Lawson, translator of de Pizan’s Treasure of the City of Ladies, who (while conceding that courtly love “may well have been an improvement over what went before”) writes in an endnote to that work:

Courtly love at whatever period was a confidence trick practiced on women …. Following the paradigm of feudalism, the lover swears loyalty to the lady as he would to a liege lord, and promises to overcome fearful obstacles and accomplish works of great prowess for her. It was a game of offence and defence in which the cards were stacked against the woman, for the illogical snag in all this was that the game which played with women’s emotions and sexual attraction, was only for men. Men might regard it as an educative pastime, but for women the results of the affair happened in the real world, where adultery, dishonor and bastardy could be capital offences.

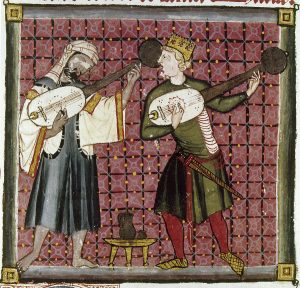

Yet at the same time, it must be kept in mind that women too played a role in promoting the ideals of courtly love – from the royal female patrons like Eleanor of Aquitaine and Marie de Champagne, who commissioned courtly romances, to the female writers who were among their authors (such as Marie de France – and more complicatedly, Christine de Pizan herself). There were also a number of “trobairitz,” or female troubadours – like Beatriz de Dia, one of the original 12th-century Provençal composers of the same sorts of songs of courtly devotion, in the Occitan language, that her male counterparts were composing:

Marie de France was not blind to the perils that courtly love could involve. In her Chaitivel she points out perils for women: “It would be less dangerous for a man to court every lady in an entire land than for a lady to remove a single besotted lover from her skirts, for he will immediately attempt to strike back.” And in her Lanval she notes the existence of perils for men also: when the queen desires the hero as a lover and he turns her down, she first accuses him privately of homosexuality (“I well believe that you do not like this kind of pleasure …. I have been told often enough that you have no desire for women …. You have well-trained young men and enjoy yourself with them”) and then (inconsistently) denounces him publicly for making improper advances toward her.

Despite these perils, Marie de France generally seems to approve of courtly love and to cheer her adulterous lovers on. Christine de Pizan, though she also wrote courtly romances, took a more critical view, as noted above; she was much more disapproving of adultery on moral grounds than was Marie de France, and also laid much more stress on the dangerous practical consequences. In her Book of the Duke of True Lovers (which translator Thelma Fenster aptly describes as an “anti-courtly courtly romance”), Christine has her authorial-voice character warn:

Christine de Pizan and her vicious dog

Do not place your confidence in these vain thoughts that many young women have who bring themselves to believe that there is no harm in loving in true love provided that it leads to no wrongful act [notice that Christine, unlike Marie, is thinking solely in terms of unconsummated relationships] and that one lives more happily because of it, and in doing this one makes a man become more valorous and renowned forevermore. Ah, my dear Lady, it is quite otherwise! … Take a lesson from such great ladies as you’ve seen in your lifetime who, without the truth of it ever having been ascertained or known, lost their honor and saw their lives ruined. There were such women; and I maintain, upon my soul, that they never sinned or acted in a basely culpable way, and you have seen their children reproached for it and less esteemed. … For let us suppose the body commits no misdeed: there are those who simply hear it said that such and such a lady is in love and they will not believe at all that there has been no wrongful act. And because of but a bit of unguarded foolishness, committed by chance out of youthfulness and without misstep, evil tongues will judge and will add things that were never thought or said. … [R]est assured that in love there is a hundred thousand times more grief, searing pain, and perilous risk than there is pleasure …. And as for saying, “I will make a man valorous,” indeed, I say that it is a very great folly to destroy oneself in order to enhance another …. And as for saying “I will have acquired a true friend and servant,” Heavens! and how could such a friend be helpful to the lady? For if she had some troubling matter, he would not dare step in to help her under any circumstances for fear of her dishonor. … Now, there are some who say that they serve their ladies whenever they do any number of things, be it with arms or in other ways. But I say that they serve themselves, since the honor and the profit remain with them and not at all with the lady!

(Yet there is a certain tension within Christine’s account. While her authorial-voice character insists that lovers “commonly … are deceitful, and in order to trick women they say what they do not intend,” and that even in those rare cases where the lovers are “loyal, discreet, and truthful,” it is still “certain” that the “ardor of such an affair does not last very long, even for the most loyal,” yet her male protagonist is presented as sincere and faithful, and at the story’s end, after he and his beloved have been forced to separate indefinitely, he reflects that he has loved his beloved, with increasing despair, “for ten full years …. [n]or has that same love passed away, nor will it disappear before we die.”)

Marie de France, for her part, lays down a challenge in her Guigemar two centuries earlier:

[W]hen there exists in a country a man or woman of great renown, people who are envious of their abilities frequently speak insultingly of them in order to damage this reputation. Thus they start acting like a vicious, cowardly, treacherous dog that will bite others out of malice. But just because spiteful tittle-tattlers attempt to find fault with me I do not intend to give up. They have a right to make their slanderous remarks.

Where Marie (like Heloïse, in her letters to Abélard; see below) celebrates sexual freedom and exuberantly defies convention, Christine condemns sexual freedom as a trap for women, and insists that women who live in a society where their lives are constrained by various sexist pressures cannot successfully act as though those pressures did not exist. Here we can see two early strands of feminism, each one embodying genuine and legitimately feminist concerns, the proper balancing of which continues to engage feminist thinkers today.

There’s Not a Trace Upon Her Face of Diffidence or Shyness

A digression on Marie de France: it’s common in mediæval writings – particularly in those not strictly academic – for the author to present the work as being written in response to someone else’s need or request. Some examples:

O Abdullah ’l-Ma’sumi, the lawyer, you have asked me to compose for you a clear and brief treatise on love. In reply let me say that I have done my utmost to win your approval and to satisfy your desire.

(Ibn Sina, Treatise on Love)Said Abu Muhammad …. Your letter reached me from the city of Almeria …. You have asked me … to compose an essay describing love, its aspects, its causes and its accidents …. [W]ere it not because I wanted to respond to you I would not have taken upon myself this work ….

(Ibn Hazm, The Dove’s Neck-Ring)I am greatly impelled by the continual urging of my love for you, my revered friend Walter, to make known by word of mouth and to teach you by my writings the way in which a state of love between two lovers may be kept unharmed and likewise how those who do not love may get rid of the darts of Venus that are fixed in their hearts. … Therefore, although it does not seem expedient to devote oneself to things of this kind or fitting for any prudent man to engage in this kind of hunting, nevertheless, because of the affection I have for you I can by no means refuse your request.

(Andreas Capellanus, The Art of Courtly Love)Fair, gentle sister … When I received your letter, in which you told me of your strong desire to be in love, I was indeed most pleased to learn of it …. I am, however, rather surprised by your request that I advise you on the means of undertaking love, and with whom. For, on such matters, none but your own heart can give you counsel. And yet, because you are my sister and have confidence in me, and because it behooves me, as a good brother, to advise and instruct you, I shall comply with that part of your request which I find possible ….

(Richard de Fournival, Counsels on Love)To a Friend …. There are times when example is better than precept for stirring or soothing human feelings; and so I propose to follow up the words of consolation I gave you in person with the history of my own misfortunes, hoping thereby to give you comfort in absence. In comparison with my trials you will see that your own are nothing, or only slight, and will find them easier to bear.

(Pierre Abélard, History of My Calamities)Since my lady of Champagne wishes me to begin a romance, I shall do so most willingly, like one who is entirely at her service in anything he can undertake in this world. [Here follows some proto-Shakespearean cleverness where Chrétien says, in effect: I will not say that my noble patron has virtues X, Y, and Z, because that would be flattery, but of course she does in fact have them. And after that:] I will say, however, that her command has more importance in this work than any thought or effort I might put into it. … [T]he subject matter and meaning are furnished and given him by the countess, and he strives carefully to add nothing but his effort and careful attention.

(Chrétien de Troyes, Lancelot)Although my desire and inclination may not have been to compose tales of love right away, since I was pursuing another interest which gave me more pleasure [Christine’s comment is, characteristically, somewhat more barbed than those of others], I want to begin a new poem now, in consideration of others’ concerns. For someone who can easily command a far more important person than myself has asked me to do so. He is a lord I am bound to obey ….

(Christine de Pizan, Book of the Duke of True Lovers)Brother Hieronymus Natalis of Ragusa … used to come frequently to visit me when I was suffering from ill-health. And when one day he saw I was less troubled with the illness, with truly humble countenance he began thus: “Beloved teacher … I should very much like to know two things from you. First, leaving aside revelation and miracles, and remaining entirely within natural limits, what do you yourself think [concerning the immortality of the soul]? And second, what do you judge was Aristotle’s opinion on the same question?” … Now I, when I saw the same great desire in all there present … I then answered him thus: … Dear son, and all you others, although you ask no small thing, for a business of this sort is very profound, since almost all the famous philosophers have worked on it; yet since you ask only something which I can answer, namely, what I myself think, for it is easy to make this known to you, therefore I gladly comply. … Therefore, with God’s guidance, I shall begin the question.

(Pietro Pomponazzi, On the Immortality of the Soul)

Some scholars are inclined to take such claims at face value, and have sometimes expended a fair bit of effort in attempts to figure out who these often vaguely-identified requesters are; others interpret such disclaimers as a literary conceit, and perhaps as a way for the author to avoid the charge of immodestly and impertinently putting forward writings nobody asked for (though such modesty doesn’t seem a likely explanation in Abélard’s case). Of course it might be sometimes the one and sometimes the other.

Marie de France with her photocopier

One thing that’s striking – and, for modern individualists, charming – about Marie de France is how free she is from any such false modesty or similar pretext. There’s no suggestion from her that she’s reluctantly making public her unworthy writings under anyone’s pressure. On the contrary, she makes clear her own enthusiasm for the composition process: “It pleases me greatly and I am eager to relate to you ….” (in Chevrefoil); “I who have set it down have had much pleasure in relating it” (in Milun). And she expresses pride and confidence in the inherent interest of her stories, in her skill in telling them, and in the likely enjoyment of the audience. In the prologue to her own collection of her courtly romances, for example, Marie writes:

Anyone who has received from God the gift of knowledge and true eloquence has a duty not to remain silent; rather should one be happy to reveal such talents. When a truly beneficial thing is heard by many people, it then enjoys its first blossom, but if it is widely praised its flowers are in full bloom. … For this reason I began to think of working on some good story …. In your honour, noble king … did I set myself to assemble lays, to compose and to relate them in rhyme …. I have put them into verse, made poems from them and worked on them late into the night. … Do not consider me presumptuous if I make so bold as to offer you this gift.

By her account here. it is Marie’s own “gift of knowledge and true eloquence,” rather than anyone else’s promptings, that has inspired her to compose her lays. Likewise, she opens her Guigemar by announcing: “Whoever has good material for a story is grieved if the tale is not well told. Hear, my lords, the words of Marie, who, when she has the opportunity, does not squander her talents.” And she begins her Milun by observing that “[a]nyone who intends to present a new story must approach the problem in a new way and speak so persuasively that the tale brings pleasure to people” – obviously with no doubt in her ability to pull off just such an achievement. Moreover, she expects her works to be cherished by future generations as well; hence her explanation in Bisclavret that she has composed this lay so that its story would be “remembered for ever more.”

Admittedly, Chrétien de Troyes can be equally forthright, as at the beginning of Eric & Enide:

The peasant in his proverb says that one might find himself holding in contempt something that is worth much more than one believes; therefore a man does well to make good use of his learning according to whatever understanding he has, for he who neglects his learning may easily keep silent about something that would later give much pleasure. And so Chrétien de Troyes says that it is reasonable for everyone to think and strive in every way to speak well and to teach well, and from a tale of adventure he draws a beautifully ordered composition that clearly proves that a man does not act intelligently if he does not give free rein to his knowledge as long as God gives him the grace to do so. … Now I shall begin the story that shall be in memory for evermore, as long as Christendom lasts – of this does Chrétien boast.

While Chrétien begins this passage with an “aw shucks” moment – gosh, my story-telling talents seem worthless to me, but who knows, maybe you’ll find some value in them – by the end of the passage this initial suggestion of modesty has quickly melted like frost in the summer sun. (By contrast, Chrétien’s comparative reticence above about Lancelot has been suggested to be an expression of his discomfort at its adulterous theme, in effect passing the buck to his patron; yet such prudishness seems a bit incongruous in an author who boasts of having translated Ovid’s Ars Amatoria.)

Into Your Tent I’ll Creep

Abélard and Héloïse making weird hand gestures

In his autobiography, Pierre Abélard recalls that Héloïse resisted the idea that they should marry, arguing that “the name of friend [amica] instead of wife would be dearer to her” since “only love freely given should keep me for her, not the constriction of a marriage tie.” And in one of her letters, Héloïse confirms her preferring “love to wedlock and freedom to chains,” telling Abélard: “God is my witness that if Augustus, Emperor of the whole world, thought fit to honour me with marriage and conferred all the earth on me to possess for ever, it would be dearer and more honourable to me to be called not his Empress but your whore” – while adding that the true prostitute is the woman who “marries a rich man more readily than a poor one and desires her husband more for his possessions than for himself,” thus in effect “offering herself for sale.”

The same idea shows up in Andreas Capellanus:

We declare and we hold as firmly established that love cannot exert its powers between two people who are married to each other. For lovers give each other everything freely, under no compulsion of necessity, but married people are in duty bound to give in to each other’s desires and deny themselves to each other in nothing.

– as well as in Richard de Fournival’s Counsels on Love:

[M]arried love is like a debt which one must pay, while the love of which I speak is a kind of grace freely bestowed. Although it is a mark of good manners to pay what one owes, still, there is no more delightful love than that born of the gratuitous favor of an artless, ingenuous heart.

(In Norman R. Shapiro, ed., The Comedy of Eros: Medieval French Guides to the Art of Love)

Hence another of the stereotypes about courtly love is the idea that love and marriage are incompatible. But there was also a strand within courtly love that held that courtly relations could be preserved after marriage. Chrétien de Troyes’s Cligès, for example (de Troyes, Arthurian Romances), ends with the lover (an Arthurian knight who, surprisingly, becomes Emperor of Byzantium) marrying his beloved, at which point we are assured:

He had made his sweetheart his wife, but he called her sweetheart and lady; she lost nothing in marrying, since he loved her still as her sweetheart; and she, too, loved him as a lady should love her lover. Every day their love grew stronger. He never doubted her in any way or ever quarreled with her over anything; she was never kept confined as many empresses since her have been.

Likewise in Chrétien’s Eric & Enide, when Enide is asked, concerning her husband Erec, “whether she was his wife or his lover,” she replies: “The one, and the other, my lord”; and later in the same story we are presented with this married couple’s passionate reunion after they “had endured so much pain and trouble, he for her and she for him”:

Now she was embraced and kissed; now she had everything she wished; now she had her joy and her delight. They lay together in one bed, and embraced and kissed each other; nothing else pleased them as much. … They vied in finding ways of pleasing each other; about the rest I must keep silent.

Moreover Chaucer, in “The Franklin’s Tale,” tells of a courtly courtship that ends in marriage, but in which the husband (Arviragus) repudiates the rights of mastery over his wife (Dorigen) that marriage traditionally entailed:

In Armorica, that’s also called Bretaigne,

there was a knight that loved and did most strain

to serve a lady as e’er best he could

and many a work and undertaking good

he for his lady wrought, ere she were won:

for she was one the fairest under sun,

and likewise born to such a high kindred,

that indeed scarcely durst this knight, for dread,

tell her his woe, his pain, and his distress;

but, at the last, she for his worthiness,

and chiefly for his meek obeisance,

had such a pity caught of his penance,

that privily she fell of his accord

to take him for her husband and her lord ….And for to lead the more in bliss their lives,

of his free will he swore her as a knight,

that never in his life he, day or night,

should for himself claim any mastery

against her will, or show her jealousy,

but her obey, and heed her will in all,

as any lover to his lady shall ….

For one thing, Sires, safely dare I say,

that friends each other ever must obey,

if they will hold long time in company.

Love will not be constrained by mastery:

when mastery comes, the god of love anon

doth beat his wings, and, farewell, he is gone.

Love is a thing as any spirit free:

by nature women do crave liberty,

and not to be constrained as though a thrall –

and so do men, if soothly I say shall.

Look who that greatest patience shows in love:

he is at his advantage all above.

(Though Arviragus does ask Dorigen to pretend to be subservient to him in public, for the sake of his manly reputation.)

Chaucer’s Arviragus and Dorigen don’t desire freedom in order to have adulterous liaisons, but rather in order to strengthen their marriage. (Adultery does indeed come into the story, but in a non-standard way: Dorigen is faithful to her husband in both body and mind, but idly grants to a prospective lover a conditional promise that she will have sex with him in the event of a certain occurrence that she assumes to be impossible. When the occurrence comes to pass, she nobly informs her husband Arviragus, who nobly advises her to keep her promised duty to the prospective lover, who in turn, abashed at such a profusion of nobility, nobly absolves her of her promise.)

Arviragus and Dorigen, Cligès and Fenice, and for that matter Abélard and Héloïse, along with similar spouses in courtly literature, are of course not calling for a radical alteration in existing institutions, but are only seeking greater personal freedom within them; one might say they are reforming marriage just for themselves, not for everybody. Nevertheless, one can see in them a germ of the later free love movement, particularly as represented by the 19th-century individualist anarchists (such as Stephen Pearl Andrews, Voltairine de Cleyre, Sarah E. Holmes, and Ezra and Angela Heywood), who opposed traditional marriage on the grounds of the legal rights it assigned to the husband over the wife (control over her property and over access to her children, plus the right to rape her with impunity), plus the dependence both economic and psychological that they took existing marriage to involve. (Héloïse’s argument that marrying for money rather than love is a form of prostitution finds a frequent echo in the free-love literature.) Many, like Andrews, advocated communal day care arrangements as a means whereby working mothers could free themselves from economic dependence on a husband. (Nowadays the idea of “free love” is often associated with promiscuity, but most free-love proponents did not advocate promiscuity – though they thought those who wished to pursue consensual promiscuity should certainly be left free to do so without coercive interference.)

Some free-love anarchists, like the Heywoods, sought to reform marriage; others, like de Cleyre, regarded the institution as irredeemable and instead sought its (of course voluntary) abolition; but they all shared a similar constellation of concerns, which are exemplified in the marriage vows of free-love anarchist Kansas activists Lillian Harman and Edwin Walker. The private ceremony began with Lillian’s father Moses Harman, himself a free-love anarchist, explaining:

Moses Harman

Marriage being a strictly personal matter we deny the right of society, in the form of church and state, to regulate it or interfere with the individual man and woman in this relation. All such interference, from our standpoint, is regarded as an impertinence and worse than an impertinence. To acknowledge the right of the state to dictate to us in these matters is to acknowledge ourselves the children or minor wards of the state, not capable of transacting our own business. We therefore most solemnly and earnestly repudiate, abjure and reject the authority, the rites and ceremonies of church and state in marriage ….

As a matter of principle we are opposed to the making of promises on occasions like this. The promise to “love and honor” may become quite impossible of fulfillment, and that from no fault of the party making such promise. The promise to “love, honor and obey so long as both shall live,” commonly exacted of woman the inferior, the vassal of her husband, and when, from any cause, love ceases to exist between the parties, this promise binds her to do an immoral act, viz: It binds her to prostitute her sex-hood at the command of an unloving or unlovable husband. For these and other reasons that will readily suggest themselves, we, as autonomists, prefer not to make any promises of the kind usually made as part of marriage ceremonies. …

As the father and natural guardian of Lillian Harman I hereby give my consent to this union. I do not “give away the bride,” as I wish her to be always the owner of her person, and to be free always to act according to her truest and purest impulses, and as her highest judgment may dictate.

Lillian Harman and Edwin Walker

I abdicate in advance all the so-called “marital rights” with which this public acknowledgment of our relationship may invest me. Lillian is and will continue to be as free to repulse any and all advances of mine as she has been heretofore. In joining with me in this love and labor union, she has not alienated a single natural right. She remains sovereign of herself, as I of myself, and we severally and together repudiate all powers legally conferred upon husbands and wives. In legal marriage, woman surrenders herself to the law and to her husband, and becomes a vassal. Here it is different, Lillian is now made free.

In brief, and in addition: I cheerfully and distinctly recognize this woman’s right to the control of her own person; her right and duty to retain her own name; her right to the possession of all property inherited, earned or otherwise justly gained by her; her equality with me in this co-partnership; my responsibility to her as regards the care of offspring, if any, and her paramount right to the custody thereof should any unfortunate fate dissolve this union.

And now friends, a few words especially to you. This wholly private compact is here announced, not because I recognize that you, or society at large, or the State have any right to inquire into or determine our relations to each other, but simply as a guarantee to Lillian of my good faith toward her. And to this I pledge my honor.

And Lillian Harman, the bride, added:

I enter into this union with Mr. Walker of my own free will and choice, and I agree with the views of my father and of Mr. Walker, as just expressed. I make no promises that it may become impossible or immoral for me to fulfill, but retain the right to act, always, as my conscience and best judgment shall dictate. I retain, also, my full maiden name, as I am sure it is my duty to do. With this understanding, I give to him my hand in token of my trust in him and of the fidelity to the truth and honor of my intentions toward him.

(For the impertinence of these marriage vows, Lillian Harman and Edwin Walker were thrown into prison for “repudiat[ing] nearly everything essential to a valid marriage.” Moses Harman was likewise repeatedly incarcerated for his free-love views, as were Ezra Heywood and many others.)

But while courtly love can be viewed as in some respects a prefiguration of free love, in other respects it comes short. For example, there’s a recurrent tension in courtly-love literature between, on the one hand, language that presents the male lover as the feudal vassal of his female beloved, and on the other hand, language that stresses the equality and mutual freedom of both partners. Both conceptions represent a reaction against the traditional subjection of women, but in rather different ways. (And the tendency of some – not all – courtly-love writings to flip suddenly from exaltation of women to misogynistic rants against them may reflect the fact that woman-as-goddess and woman-as-demon are both forms of woman-as-opaque-and-other, and thus the former as much as the latter can involve deflection from the male lover’s actual engagement with the female beloved as a person.)

As an instance of a work that shifts between equality-of-lovers and subjection-to-the-female within the space of a few lines, consider Marie de France’s Equitan, in which a woman tells her royal would-be lover: “If it should come about that I loved you and granted your request, our love would not be shared equally. Because you are a powerful king and my husband is your vassal, you would expect, as I see it, to be the lord and master in love as well. Love is not honourable, unless it is based on equality.” The king responds, not by promising her a relationship of equality, but rather by promising to reverse the inequality: “My dearest lady, I surrender myself to you! Do not regard me as your king, but as your vassal and lover. I swear to you in all honesty that I shall do your bidding. … You can be the mistress and I the servant; you the haughty one and I the suppliant.” – and to this the woman happily agrees, her earlier insistence on equality apparently forgotten, and the two hop into bed.

The feminist dimension of courtly love is further problematised by the tradition’s inconsistent attitude toward female consent. Andreas, in his definition of love, stresses the need for “common desire”; and his rules for lovers include such precepts as “In practicing the solaces of love [i.e., intercourse] thou shalt not exceed the desires of the lover,” and “That which a lover takes against the will of his beloved has no relish.” He also advises that the lover should be “restrained in his conduct,” and “should do nothing disagreeable that might annoy” his beloved, and further notes:

Love therefore leaves it to the woman’s choice, so that when she is loved she may love in return if she wishes to, but if she does not wish, she shall not be compelled to …. And we believe that this is done after the example of the Heavenly King, who leaves each man to his own free choice ….

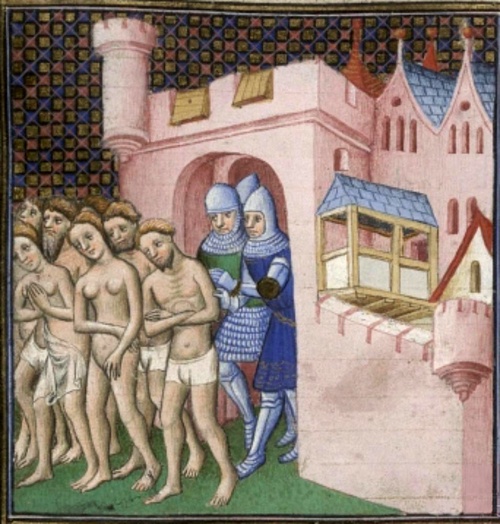

So far so good. But when he turns from the pursuit of upper-class or middle-class women to the pursuit of peasant girls, all his high talk of free will and mutual consent goes out the window, as Andreas now advises: “do not hesitate to take what you seek and to embrace them by force,” since “you can hardly soften their outward inflexibility so far that they will grant you their embraces quietly or permit you to have the solaces you desire unless first you use a little compulsion as a convenient cure for their shyness.”

Other mediæval courtship manuals (many taking some hybrid of Andreas and Ovid as their model) are still freer with this sort of advice, evidently not restricting the legitimacy of rape to any particular social class – though, to be sure, they cloak what they are advising in the familiar excuse that the woman “really wants it.” Thus for example:

Even if you see Fear tremble, Shame blush, and Rebuff shudder, or all three groan and lament, do not give a fig for that but pluck the rose by force and show that you are a man … for nothing could please them so well as that force, applied by one who understands it. For many people … want to be forced to give something that they dare not give freely, and pretend that it has been stolen from them when they have allowed and wished it to be taken. And so you may be sure that they would be sad to escape by this defence … however great the joy they feigned ….

(Jean de Meun, Romance of the Rose)Of course the lady may, perchance,

Seem to reject your rash advance,

Commanding – though her lips were kissed –

That you shall straightway cease, desist

And call a halt! But though she act

Haughty and harsh, in point of fact

She really hopes that you ignore

Her protests and persist the more,

Forcing her feeble flesh until

Love lays her low “against her will”!

(For never would her lips admit

That all her qualms are counterfeit,

And that, in spite of sigh and tear,

She prays you boldly persevere.)

So let her weep and whimper “nay”;

I warrant she’ll not run away

Even though she be able to.

No, no! She loves that derring-do

Of brazen cavalier, undaunted.

She would feel hurt, unloved, unwanted

Were you to leave her there, forsaking

What you might have just for the taking. …

Despite the prudish pose she flaunts,

Give her what every woman wants!

(Anonymous 13th-century French Key to Love; in Shapiro, Comedy of Eros, op. cit.)Later, if you should be alone with her, request

A kiss – but tactfully – and if she should protest,

Then kiss her all the same, as if in idle jest.

Ladies who answer no, wish they had acquiesced. …

Kiss her and hold her fast. Then, gently taking care

To do no harm or hurt, lay her down then and there ….

Now when she feels your hand, she may, indeed, demur.

She may cry out: “Off, off! I do not like you, sir!”

But let her shout and shriek her fill: you shall not stir.

Press your bare bodies close, and do your will with her.

(Guiart, L’Art d’Amors (13th century), again in Shapiro.)

Relatedly, Don Monson, in his book Andreas Capellanus, Scholasticism, and the Courtly Tradition, discusses a form of French troubadorial love-poem, called pastorela in the south and pastourelle in the north, that narrates an “encounter and conversation of a knight with a comely shepherdess in which he tries to seduce her,” thus reversing “the usual social relationship of the love song, which typically represents a poet-lover of modest origin wooing a highborn lady.” In some versions, “the shepherdess puts up a witty and spirited resistance, turning all the knight’s efforts to ridicule”; other versions feature “shepherdesses who are less recalcitrant or, especially in the northern French pastourelles, who are won over by the promise of gifts or the use of force.” Monson observes that “38 of 160 Old French pastourelles, or … 24% … include rape scenes, whereas … only one such scene [is found] for 30 Old Occitan pastorelas.” This difference between north and south, for Monson, aligns with a difference in attitudes toward class between the two regions:

When the ideas of the troubadours were introduced into northern France in the mid-twelfth century, they encountered a much stronger class sentiment on the part of the northern aristocracy than that which prevailed in the South. Moreover, this sentiment increased on the course of the century, as the French nobility consolidated its position. In the courtly romances, which constitute the most important expression of courtly ideas in the North, all the protagonists are noble, and social mobility is hardly ever an issue. This thematic difference appears to reflect a difference in social climate underlying the literatures in Old French and Old Provençal.

Monson invokes the conflict between the “egalitarian tendencies of the troubadours and the greater class consciousness of the northern French courts” to explain why a lowly peasant girl’s resisting an aristocratic knight’s advances might seem less tolerable to northern than to southern audiences, thus resulting in a higher tolerance for resolutions involving rape. Whether this explanation could also cover a higher tolerance for rape in general, in other northern French works such as those cited above, is less clear.

In any case, this toleration for rape was one strand within the courtly-love tradition, coexisting with another strand that strongly condemned rape. Using force on women is treated as a violation of courtly behavior in, for example, Chaucer’s “Wife of Bath’s Tale,” where a knight of the Round Table who rapes a random girl he meets on the road is condemned to death by King Arthur; likewise, in another Arthurian romance, Wolfram of Eschenbach’s Parzifal, the hero takes a kiss by force because he has been improperly instructed in courtly behavior, and later laments: “I was a young fool – no man.” Compare also the Confessio Amantis by John Gower (14th century):

“… So be there, in the like same wise,

lovers, as I shall thee devise,

that when naught else may them avail,

anon with strength they do assail

and if chance favourable should happen,

seize the love they seek by rapine.

Wherefore, my son, confess thou here

if thou hast been a ravener

of love.” “Indeed, O father, no:

for I my lady do love so,

that though I were as was Pompey,

that all the world would me obey

or else like Alexander king,

I would not do so foul a thing;

they are no good men, who so do.”

“In good faith, son, thou speakest true. …”

Chrétien de Troyes splits the difference: in Lancelot, describing (without evident approval or disapproval) the supposed rules of the vaguely earlier Arthurian era, he tells us:

The customs and practices at this time were such that if a knight encountered a damsel or girl alone – be she lady or maidservant – he would as soon cut his own throat as treat her dishonourably, if he prized his good name. And should he assault her, he would be for ever disgraced at every court. But if she were being escorted by another, and the knight chose to do battle with her defender and defeated him at arms, then he might do with her as he pleased without incurring dishonour or disgrace.

This is quite a nasty Catch-22 for the woman. If a woman travels alone, she is safe from men who follow the chivalric code – but not from those who do not. If she travels with an escort, then she is unsafe from anyone, code-follower or not, who can defeat her escort. (Maybe the idea is that a man “deserves” the privilege of raping a woman only if he has to fight for it?)

Who Wrote the Book of Love?

BIANCA: What, master, read you? First resolve me that.

LUCENTIO: I read that I profess, The Art to Love.

BIANCA: And may you prove, sir, master of your art.

LUCENTIO: While you, sweet dear, prove mistress of my heart!

(Shakespeare, Taming of the Shrew; usually taken as a reference to Ovid’s Ars Amatoria, but given the overall characterisation of Lucentio, and of his relationship with Bianca, I think possibly a reference to Andreas Capellanus’s De Arte Honeste Amandi instead)

I’ve mentioned Andreas Capellanus several times already. For a long time his book was regarded as the authoritative source on courtly love – the lens through which to read the courtly romances and troubadour songs. But this is probably a mistake. Andreas was seeking to codify an already existing tradition of poets who had been working with no thought for Andreas; and the De Arte Honeste Amandi seeks (and, given its multiple internal inconsistencies, arguably fails) to impose a uniform schema on a diverse variety of works that had been composed with no such schema in mind.

In the De Arte, Andreas undertakes, in Monson’s words, “on the one hand, to systematize the thematic material of the vernacular love poetry and, on the other, to reconcile the poetic themes with Christianity and with Ovid.” This, as Monson notes, is a tall order, since “the poetic themes are full of inconsistencies,” and in any case “the doctrine of the troubadours, insofar as we can speak of them as having a doctrine, is probably not reconcilable ultimately with either Ovid or Christianity, let alone with both of them,” inasmuch as courtly love poetry tends to “steer a middle course between the urbane cynicism of the Ars amatoria and the austere asceticism of the Fathers, producing a kind of idealized sensuality.” In particular, the Ovidian strand in Andreas’s book is much stronger than in most of the poetic material he’s responding to, giving his book some of the flavour of a manual for pick-up artists. Peter Dronke, in his book Medieval Latin and the Rise of European Love-Lyric, suggests that, e.g., Chrétien de Troyes would have seen in Andreas nothing more than an “amiable rascal.”

There is also a certain Scholastic air to much of Andreas’s discussion; his dialogues between lover and beloved, for example, resemble, as Monson points out, “that form of public debate which the Middle Ages called ‘disputation’.” (Compare also the Andreas-influenced Romance of the Rose, a purported narrative of the progress of a courtship, in which the various allegorical figures give long speeches about everything from the relation between church and state to Boethius’s solution to the problem of divine foreknowledge.) I don’t mean to suggest that such material was always completely alien to the love-poets; for example, the 13th-centtury troubadour Guido Cavalcanti invokes terminology from Aristotelean metaphysics and psychology (“to bring to bear a bit of natural science,” as he puts it) in order to explain the nature of love (“An accident that often fiercely smarts”) as well as its origin (“Where love is born, or who created love”):

In that part where memory has its locus

He takes his state and there he is created ….

He comes from an image seen and comprehended

That’s apprehended in the Possible Intellect …

(In Wilhelm, Lyrics of the Middle Ages)

But it is hardly standard.

The biggest puzzle about the De Arte Honeste Amandi is the unexpected repudiation, in Book III, of everything Andreas has been saying in Books I-II; suddenly love goes from being an ennobling, morally improving force to being an insidious influence that leads us on to various crimes, while the reverential (if somewhat manipulative) attitude toward women that characterised Books I-II gives way to a misogynistic rant about women as vessels of iniquity that’s a bit over the top even by mediæval standards. (Though Books I-II are not unproblematic on this score; for they show, as Monson puts it, “the very delicate position a woman finds herself in … upon being solicited by a suitor. If she gives in too easily, it will be assumed that she is motivated by excessive carnal desire, with the further assumption that she is likely to be unfaithful …. If, on the other hand, she holds out too long, it will be assumed that she is interested only in stringing the man along to get his money. In short, she is either a slut or a prostitute.” For Monson, this Catch-22 “illustrates the depths of the Chaplain’s misogyny” even more than does “the anti-feminist diatribe of Book Three.” But even so, there is certainly a vast difference both in explicit doctrine and in overall tone between Books I-II on the one hand and Book III on the other.)

So what’s going on? There are several possibilities:

Each of the above interpretations has had its vigorous defenders, and each can find some textual evidence in its favour.

But the inconsistencies are not just between I-II on the one hand and III on the other. There are plenty of inconsistencies to be found just in the earlier part; for example, Andreas seems to commit himself to all of the following claims:

In addition we can add the fact that the dialogues are supposedly intended to show men what arguments to use in order to woo women successfully, yet in many of the dialogues the attempts fail, and the women essentially call out the arguments as bullshit.

Similar tensions are to be found in many other mediæval love manuals; Robert de Blois’s 13th century Discipline for Ladies, for example, urges women to remain faithful to their husbands – but also gives them advice on how to proceed if they want to take a lover.

Fournival’s Bestiary of Love

While bearing some superficial similarities to Andreas’s work, the Counsels on Love by Richard de Fournival (1201-1260) strikes a rather different note. In place of Andreas’s rather cold analytical approach, Fournival rhapsodises: love, he tells us, is “a folly of the mind, an unquenchable fire, a hunger without surfeit, an agreeable illness, a sweet delight, a pleasing madness, a labor without repose and a repose without labor.” It is also “the root of all virtues and the substance of all good”; nor is it possible to “explain from whence it comes or how it is conceived,” since it is “born of the heart’s unrestrained caprice.” Indeed, “love’s capriciousness is such that reason does not even try to examine it.” (In Shapiro, op. cit.) Contrast Andreas’s more sober and Scholastic definition of love as “a certain inborn suffering derived from the sight of and excessive meditation upon the beauty of the opposite sex, which causes each one to wish above all things the embraces of the other and by common desire to carry out all of love’s precepts in the other’s embrace.”

Of course the most obvious difference between Fournival and Andreas is that Fournival offers no palinode, instead insisting that “even when I have been so tormented by love that I could neither eat nor drink, sleep nor rest, even then I have never doubted the value of love and its sweet charms,” so that “despite all those who choose to censure love, I for one shall always commend it to you.”

James Wadsworth and Betsy Bowden (in their notes to Shapiro’s anthology) write that Fournival’s conception of love is “not courtly,” since he “does not consider adultery a necessary ingredient” (but who does? Andreas comes closest, but he is a commentator on and developer of the genre, not an originator of it), and “has no thought of the remote domna of the Provençal lyric, the haughty lady whose cold, endless refusals bring endless suffering to the groveling suitor” (as if this were the only way things go in Provençal love lyrics). Rather than being courtly, we’re told, Fournival’s conception of love is “romantic,” in that it “assumes the coloring and the principal motifs of the great twelfth-century French romances of which it is, in fact, a codification.” But since when are the 12th-century romances not considered paradigm cases of courtly-love literature? In any case, Andreas’s book is clearly likewise intended as, inter alia, a codification of the themes of the 12th-century romances. So it’s not clear why Fournival’s work is any less “courtly” than Andreas’s. If Fournival’s and Andreas’s essays have a rather different tone, it’s because they were very different sorts of writers, drawing different lessons from the same material.

The Gal Who Invented Kissing, I Don’t Recall Her Name

Oceans of ink have been spilled over the question of the origins of courtly love (including the suggestion that it represents a survival of the pagan worship of nature goddesses). I won’t attempt a full survey here, but I do want to touch on some of the more notable treatments.

One of the most influential accounts of courtly love is that of C. S. Lewis in his 1936 book The Allegory of Love: A Study in Medieval Tradition – though he is in large part repeating views that were already current, as he himself notes up front:

Every one has heard of courtly love, and every one knows that it appears quite suddenly at the end of the eleventh century in Languedoc. The characteristics of the Troubadour poetry have been repeatedly described. … The lover is always abject. Obedience to his lady’s slightest wish, however whimsical, and silent acquiescence in her rebukes, however unjust, are the only virtues he dares to claim. There is a service of love closely modelled on the service which a feudal vassal owes to his lord. … The poet normally addresses another man’s wife, and the situation is so carelessly accepted that he seldom concerns himself much with her husband: his real enemy is the rival.

As we’ve already seen, this characterisation depends on the usual one-sided diet of examples. In fact the lover is not “always abject,” the beloved is not “normally … another man’s wife.”

But assuming the inherent link between courtly love and adultery, Lewis proceeds to explain it: