More juvenilia: “One Flew Through the Electrostatic Converter” and “The Life and Times of Captain Cosmos” (both age 13).

For Whom An Alien Heat Makes Festival, Part 5: PREDATORS and PROMETHEUS

SPOILER WARNING:

Predators (2010):

What Predators and Prometheus have in common is that they’re the first of all these films since Alien to feature humans exploring a previously unknown planet. (And in both movies the explorers literally declare the planet “Hell.”)

What Predators and Prometheus also have in common is that they both represent attempts to reignite their respective franchises while ignoring the AVP films – yet neither quite succeeds in putting AVP behind it. I’ll discuss Prometheus’ debt to AVP below; in the meantime, here’s IMDB’s list of some of the ways in which Predators continues in the Alien/AVP tradition:

Even though this installment in the “Predator” franchise explicitly wanted to part with the crossover AvP story arc, it does contain at least three nods to the “Alien” franchise: – 1) at one point, while (obviously, given the movie’s universe) facing near-certain death, one character tells another “If the time comes, I’ll do us both”, a reference to Hicks’ almost identical line in Aliens, 2) when the group finds the body of an earlier victim of the antagonists, he has a large hole in his chest with the ribs bent outwards, referencing the way xenomorph young emerge from their host and the wound found on the “space jockey” in Alien, 3) as soon as Royce recovers from his parachute landing; as he looks around a music motif from Aliens can be heard and when the group enters the Predators camp there’s a brief view of an Alien skull on the ground. …

According to director Nimród Antal, the lower jaw attached to the mask of the Berzerker Predator is that of an alien from the Alien movie series. …

Alice Braga (who plays an Israeli soldier) is the third brunette actress who appears in the “Predator” series, following Elpidia Carrillo in Predator and Maria Conchita Alonso in Predator 2, while Sanaa Lathan played the female leader in AVP: Alien vs. Predator following Sigourney Weaver who played the female leader role in “Alien”

I would add: a) Predators has the Predators customarily hunting in groups of three, something that was established only in AVP (since previous movies featured solo Predators); b) the scene at the end where Royce and Isabel finally tell each other their names is a nod to a similar scene between Hicks and Ripley at the end of Aliens; and c) Robert Rodriguez, the film’s producer and screenwriter, has acknowledged that the title Predators is consciously modeled on Aliens. Moreover, there’s nothing in Predators that’s clearly inconsistent with the Alien and AVP films, nothing that rules out their all sharing the same universe. (If it matters.)

Alas, poor Yorick!

Predators is the best of the Predator movies. One of the main reasons for this is that it has the best characters and the best casting choices, with Adrien Brody, Laurence Fishburne, and Louis Ozawa Changchien (now there’s a multicultural name for you) being especially felicitous. (I’ve seen an inadvertently hilarious online interview clip about Predators where Rodriguez is saying “this group of killers” and the subtitles mistakenly render this as “the Scuba-Killers,” so that’s what I’ll call them.)

The film is not without its plot holes, however. For example, in order to identify a prisoner on death row and know what crime he’s committed, the Predators must be able to understand some human language (presumably English, since it’s an American prisoner). And we know from the previous films that the Predators can produce English words. (In Predator 2 a Predator does this with his mask off, seemingly establishing that they can produce human speech with their own voices, not just some sort of synthesier.) Yet both in this movie and in AVP, communication from Predator to human is done solely with hand signals. One might also cavil at the astronomically implausible sky, and the unexplained spinning leaf.

A few random notes:

Unlike the other films, there’s no real governmental or corporate perfidy in Predators (apart from the general critique of professional killers working for same), but they do go the Ash/Burke route of having one of their own (actually two, in a way) turn out to be a betrayer.

Fishburne’s character, Noland, wears Vietnam-era army duds and hums Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyrie,” thus permitting speculation that he might be the same person as Fishburne’s character Tyrone Miller in Apocalypse Now.

At one point Noland tells the Scuba-Killers: “They drop in fresh meat, hunt it, and kill it. In that order.” Well, of course in that order; what order was he expecting? (First kill, then hunt: Predators vs. Zombies?)

Royce’s “say goodbye to your little friend” is a nod to Scarface. (I can’t shake the worry that Noland’s split personality might have been introduced into the story solely in order to enable this punchline. I mean, this is a Rodriguez script, after all.)

You must have big rats ….

By contrast with the other defeated Scuba-Killers, we never actually see Hanzo definitely dead, thus permitting speculation that he might return in a sequel.

Hanzo’s name is Rodriguez’s nod, in part to actual Japanese history, but primarily to his friend’s movie.

Hanzo’s remark about the age of the samurai sword makes me wonder why there haven’t been any Predator films set in premodern times. It wouldn’t be hard to turn Beowulf into a Predator story: Predator vs. Vikings!

There are deleted scenes available on the blu-ray but not the dvd, so I haven’t seen most of them, though I did find a few online. One was reminiscent of Clemens’ story in A3, though presumably differing in truth-value; another included a sexual proposition similar to one in Prometheus, but with a different result. The dvd includes three animated prequels, but they don’t add much; apparently there are more on the blu-ray.

Prometheus (2012):

So a team of archeologists financed by Weyland Industries is lured to an alien structure with ties to several ancient earth cultures – ties that enable the team to decipher the inscriptions. Old man Weyland, the CEO, is himself along for the trip, seriously ill, grappling with own mortality and seeking answers. The structure is apparently, but not actually, deserted, and is also highly automated. The team’s progress through the structure is displayed on a hologram. Within the structure, the team soon finds itself in the middle of a conflict between tall high-tech humanoid aliens and creepy-crawly xenomorphs that gestate inside other life forms; some characters are killed by the humanoids and others by the xenomorphs. Two minor characters, one friendly and one hostile, who initially haven’t gotten along, join forces inside the structure only to be killed early on. At the end the chief viewpoint character, a woman, is the sole surviving human, the last surviving humanoid alien having been killed a few minutes earlier. The second to last shot is an alien spaceship leaving the planet; the last shot is a new type of xenomorph bursting from the chest of the dead humanoid alien.

Is that the plot of AVP or ofPrometheus? Well, both – which, as I mentioned last time, makes Scott’s contemptuous dismissal of AVP rather churlish and ungrateful. Hell, Prometheus even follows AVP continuity by portraying AVP’s Weyland company as not yet merged with AVP:R’s Yutani company to form Alien’s Weyland-Yutani. (Scott’s official online timeline for Weyland Industries is certainly inconsistent with AVP, but then such online material is not actually part of the movie, so its canonicity is as up for grabs as everything else’s.)

Admittedly, Prometheus does it all better than AVP, with far more nuance and beauty. (Well, except for Weyland himself; AVP’s Charles Bishop Weyland is actually a more interesting and fully realised character than Prometheus’s Peter Weyland. But Prometheus beats AVP in every other respect, and of course is absolutely spectacular visually.)

Prometheus’s debts don’t end with AVP. The plot of Prometheus is so similar to that of Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (which was, as you’ll recall, a major inspiration for AVP) that Guillermo del Toro has, alas, put on hold his plans for a movie version of the Lovecraft novel for fear of duplication. There are also similarities to Star Trek V (of course a much worse movie than Prometheus): a starship travels to a supposedly paradisiacal planet to meet God, and then there’s screaming and dying. And there’s at least one striking parallel with Scott’s earlier (and still superior) Blade Runner: in both movies, a human and an android pay a visit to the creator of one of them, who asks for more life from his creator – and doesn’t receive the answer he’s hoping for.

But the movie that’s the clearest model for Prometheus, apart from AVP, is (the likewise superior) 2001: A Space Odyssey. The opening shots of Earth from space behind the disk of the moon are extremely similar; then we see a scene from Earth’s prehistory, featuring alien intervention in human origins; then we jump to the near future, with scientists digging up an ancient alien artefact; next we jump several months later to a spaceship that is heading from Earth to another planet to investigate the artifact’s origin, with a human crew (some still in cryosleep and some not) and a soft-spoken, unreliable A.I. From there the plots diverge – one’s a monster movie, one isn’t, and the difference isn’t to Prometheus’s advantage – though they do both end with the birth of a new and unsettling lifeform.

There are even some similarities in dialogue: Holloway asks Vickers, as HAL asked Bowman, whether there’s a secret agenda behind the mission, while David’s quasi-apology to Shaw is reminiscent of HAL’s telling Bowman – after killing most of the crew – “I know I’ve made some poor decisions recently, but I give you my assurance that my work will soon be back to normal.”

Much ink has been spilled (well, pixels, really) over the question whether Prometheus is a prequel to Alien. It may not be a prequel in the standard sense, but its connection to Alien is certainly stronger than just happening to take place in the same universe, with the same company and the same alien ships. Admittedly we never see the xenomorph until the end (and even then it’s not qute our xenomorph), but Scott teases us with the prospect of the xenomorph throughout the film, from the bas-relief sculpture of a xeno-queen, to the Engineers that seem to have died of xenomorph, to the critters that, if they aren’t classic “facehuggers,” are certainly in the same line of work. We even get the suggestion that humanity owes its life to the xenomorphs, since a xenomorph outbreak on their ship seems to be all that prevented the Engineers from completing their plan to deliver xenomorphs to Earth. And of course, even though they’re not the same Engineer, we now understand why, back in Alien, the pilot’s skeleton appeared to have grown into its chair. (Perhaps in the sequel it will turn out to be Shaw inside?)

I said above that nothing in Predators was inconsistent with the AVP films, leaving viewers free to regard them as canonical if they so choose. It’s less clear whether that’s true of Prometheus. There would be some awkwardness, though nothing insuperable, in its turning out that two unrelated alien races have been interfering with ancient human cultures (sometimes exactly the same cultures). The real question is whether xenomorphs have been around long enough for Predators to have been ferrying them to Earth since before the rise of Egypt. Some viewers think the critter at the end is supposed to be the first xenomorph, or an ancestor of the xenomorphs, but from the murals in the main chamber it’s clear that something xeno-queen-like has been around for a long time. Perhaps this will be settled in a sequel.

Counting xenomorphs on the wall, that don’t bother me at all

The chief question to be addressed in the sequel is why the Engineers first created us and then decided to destroy us (though David warns the crew that the answers might be disappointing). Some have suggested that the Engineers have turned against us because we’ve grown too technologically advanced and now pose a threat to them – but remember that their decision to wipe out humanity (if David has interpreted them correctly, and is telling the truth) was made two millennia ago. Scott had apparently flirted with the idea of Jesus’ being an emissary of the Engineers, and their change of mind being revenge for his crucifixion. That certainly would have given a different twist to Dillon’s apocalyptic faith in A3; but it doesn’t make much sense for the Engineers to say, “you refused to listen when we advised you to love and forgive your enemies, so now we’re going to go xenomorph on your ass.” Although Scott dropped the idea, we still have the ship arriving at Christmastime, and the business with Shaw’s cross, and the Biblical trope of a barren woman named Elizabeth being made miraculously pregnant, so a Christian theme of some sort is definitely in play.

How does the film’s story connect with the myth of Prometheus? It’s not clear. The Engineer who sacrifices himself at the beginning of the film seems to be introducing Engineer DNA into human DNA, and thus in effect bringing us fire; but there’s no sense that he acts with the other Engineers’ disapproval. The ship’s daring to come to LV-223 might represent human overreaching – except they were invited. The Engineer’s violent reaction to David might suggest that humans’ daring to become creators of life ourselves might be the offense (recall, too, that the subtitle of Frankenstein is The Modern Prometheus) – but again, that could hardly be what set the Engineers off 2000 years ago. There’s also an ongoing theme, voiced explicitly by both David and Vickers, of the desire to displace one’s parent/creator, but in their case the focus is Weyland; the humans didn’t come to LV-223 to displace the Engineers (though one can see the xenomorphs as taking on that role).

Don’t count on me, I Engineer

Prometheus has been hailed as a film that tackles philosophical and religious themes. Now science fiction is in fact an ideal medium for the exploration of such themes, since, like philosophy, sf takes as its field the boundaries of the possible, and not merely of the actual. Indeed, many of the traditional sf plots are likewise traditional philosophical thought-experiments: what if we could make ourselves invisible? what if our daily experience were merely a simulation? what if someone disassembled you and then reassembled the parts exactly as they’d been before? what if robots demanded rights? what if we could see our own future? what if there were no government? what if by torturing one innocent person you could make everyone else vastly better off?

It has to be said, however, that Prometheus’ engagement with philosophical issues is shallow and muddled. To begin with, the question of whether we were genetically engineered by aliens is a scientific question, not a philosophical one. (It also has nothing to do with the question of what happens when we die, a question with which it is inexplicably linked throughout the film.) The question of how our self-conception as humans should be affected if we were to discover that we were so engineered is a philosophical question; but the answer, surely, is “not much.” What we are and can be should matter more to our self-conception than what caused us to be as we are. The question “what is my purpose in life?” is not answered by inquiry into the purposes of one’s creators; if you find out that your parents deliberately conceived you in order to sell you into slavery, it doesn’t mean you ought to be a slave.

Now in fairness, it could be argued with some plausibility that this is precisely the point that the film is trying to make; hence David’s point about the Engineers’ answers to humanity being potentially as disappointing as humanity’s answers to him. But the question is never engaged; when, at the end, David asks Shaw why she’s so intent on finding the Engineers’ homeworld, she simply tells him he doesn’t understand because he’s a robot, and then zips him up in a bag. Admittedly she has good reasons for bearing David some hostility; but it’s hard to explore philosophical questions when, of your three main characters (Shaw, Vickers, David), the first two persistently refuse engagement with philosophical inquiry, while the third shows some interest but seldom speaks about it, and when he does he’s quickly dismissed (e.g. by Holloway and Shaw).

We also have the philosophic idiocy of Shaw’s worrying that she’s not fully human because she can’t bear children (though at least it’s subverted when she finds out being pregnant is not what it’s cracked up to be).

The film’s handling of religion is, if anything, even worse. Shaw is supposed to be a “woman of faith,” but her faith is never shown as having much content; and the film’s conception of faith is “choosing to believe,” which is not generally what faith means to actual believers. Moreover, in the real world you’re unlikely to win the support of top scientists and billionaire investors by telling them that you “choose to believe” that your project will succeed.

Another problem with the film is the incredible incompetence and disorganisation of the spaceship crew. First, they can’t seem to agree as to who’s in charge: Weyland says Shaw & Holloway are in charge, Vickers says she’s in charge, and many of the characters act as though they think Janek is in charge. Shouldn’t they sort this out before heading off to explore the Alien Labyrinth of Death? There were similar disagreements in Alien and Aliens, but they were much narrower in scope, and there were actual attempts to settle them.

Moreover, they can’t seem to keep track of where their fellow crew members are. When they get back to the ship on the first day, it takes an unconscionably long time for them to realise they’ve left two people behind. Also, apparently there’s no procedure for recording incoming transmissions from missing crewmembers when no one’s on duty to hear them live. (Not to mention the inexplicability of no one’s being on duty to hear them. Okay, so I totally understand abandoning one’s post to have sex with Charlize Theron, but why is there only one person on duty at night, when the ship is sitting on an unknown and potentially hostile planet? and why is it the captain, who also seems to be on duty during the day? and given that he’s the captain, why can’t he order someone to take over for him?) And how, on any well-run ship, can one hide an entire extra room, complete with an extra passenger, without the captain or most of the crew being aware of it?

A three-hour tour …

The most hopeless of all the crew, of course, are the two doofuses that, to nobody’s surprise, are the film’s first victims. It strains belief that on encountering their first extraterrestrial life, their reaction is to argue with each other as to whether it looks more male or female (the point seems moot, since what it looks like is a vagina at the end of a penis; of course the xenomorph itself, or at least its head, has sometimes been described that way, but this is … more so) while trying to pet it. Yes, people can be that stupid (every year, tourists at Yellowstone get gored as a result of trying to climb on top of bison – evidently on the theory that the bison look so calm and placid when you’re not trying to climb on them that they’re bound to be equally laidback when you are) but one doesn’t expect such idiocy from a hand-picked scientific expedition. (Didn’t Alien also feature a comic-relief duo? Yes, but not to the same extent; and Parker and Brett certainly never tried to pet the xenomorph.)

Of course the two doofuses aren’t the only idiots on the crew. What about Holloway, who removes his helmet merely because the alien chamber contains breathable air, with no concern about possible infections? And if you looked in the mirror and noticed you had tiny worms coming out of your eyes, would you mention it to anyone, or would you just head back happily to the alien site you were investigating yesterday?

There are other problems: Why would the Engineers speak the same language they spoke thousands of years ago (Proto-Indo-European, apparently)? That wouldn’t be a safe assumption in our own case. Revisiting the Hulk problem, but much more massively (literally), how did Shaw’s cthulhoid baby grow so huge while locked in the medlab? What is there for it to feed on in there? And why doesn’t David know the difference between “thesis” and “hypothesis”?

All previous Alien movies have, inter alia, two constants: Ripley, and a surprising android. (Ash was surprising because he turned out to be an android, and evil. Bishop was surprising because he turned out not to be evil. Then in A3, Bishop was surprising because he turned out to have an evil human creator or evil android brother, depending on whether you accept AVP as canonical. After that, Call was surprising because she turned out to be an android and a free-will agent. Notice, incidentally, that Scott has continued the extradiegetically alphabetical android naming convention from the previous films; notice, too, that they’re all names with religious connotations, for what it’s worth.) Prometheus has the most complex and enigmatic android yet, but no Ripley. In a sense, though, we might see Prometheus as splitting Ripley into two characters, Shaw and Vickers, in much the same way that a transporter accident once split Captain Kirk into two versions, one nice but weak and ineffective, the other forceful but sinister.

Admittedly that’s an overstatement. Shaw may not be forceful, but she’s determined, and far from weak; and while Vickers is no Ms. Congeniality, she’s not portrayed as evil (particularly by this series’ standards for corporate representatives) – indeed she made me wish Theron had gotten her wish to play Dagny Taggart. Her (eminently sensible) refusal to let contaminated crew members back onto the ship may make her seem unsympathetic, but remember that this is exactly what Ripley did in the first movie. Vickers might be said to represent Ripley’s hardass, skeptical, super-competent side, while Shaw represents Ripley’s gentler, less corporate, more honest, and frankly more courageous side.

Unfortunately, splitting these aspects of Ripley’s persona apart weakens both characters, particularly from a feminist standpoint: in Ripley’s stead we now have the unsympathetic “masculine” “bitch” and the naively trusting “feminine” “ditz.”

Moreover, I thought Noomi Rapace’s performance was substantially outshone by Fassbender’s and Theron’s. Now I haven’t yet seen the Swedish version of Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, but I’ve seen clips from it, and while I can’t imagine that her version of Lisbeth Salander could be better than Rooney Mara’s, it still looks pretty good, and has been well reviewed, so I know she’s capable of playing tough and edgy. Thus the flaw may well be in the character rather than the actress – but Shaw just struck me as a bit bland and boring. (Incidentally, Theron was initially cast as Shaw, which would have made a very different movie.)

The Vicker of Dibley

The name “Elizabeth Shaw” is also associated (whether coincidentally or not, I’m not sure – though Scott is certainly familiar with the show, having originally been scheduled to design the Daleks, and what an alternative universe that would have been!) with a Doctor Who character – the first companion of the third Doctor, back in 1970. That Shaw (played by the late Caroline John) was a more skeptically-minded scientist than the one in Prometheus, but there are nevertheless some parallels: in the four stories she was in (note: more screentime than it may sound like, since those four stories were spread over 25 episodes), she was menaced by homicidal synthetic humans, deadly alien ambassadors, and two ill-fated drilling projects, one that awakens humanity’s intelligent prehuman precursors, and one that releases a force that transforms humans into belligerent monsters.

As with Hanzo in Predators, there’s been speculation that Vickers may be alive. Yes, we saw an alien starship fall on top of her, but we saw the same ship fall on Shaw, so who knows? Besides, if she’s not dead, who is the xenomorph from the last scene going to menace in the sequel? Unless we’re being shown events out of sequence (always a possibility: I’m sure some viewers of ESB thought two probes had landed on Hoth), Shaw and David have already taken off in the Engineers’ ship when the xenomorph hatches back on the planet.

There’s also been speculation that Vickers is an android, but I think that would be a bad idea: David would lose his distinctness, and his oddness of affect would be unexplained, given that Vickers doesn’t share it; Vickers’ resentment against her father’s preferring an android son to a human daughter would also lose much of its point. (Admittedly, though, if she’s an android it would be easier to sell her survival. And she does have a religiously-oriented name, if you spell it differently. And although her name begins with V rather than E, E is at least the Vth letter of the alphabet ….)

Shaw and David visit a head shop

The character of David raises the most questions. To what extent is he following Weyland’s orders and to what extent is he acting on his own initiative? In particular, is his slipping Holloway the DNA cocktail driven by a) Weyland’s instructions to “try harder,” b) David’s resentment at Holloway’s calling him “not a real boy,” or c) David’s own quest for answers? If David takes Holloway’s answer to the question “how far would you be willing to go?” as validation for his own actions, does that mean he would have acted differently if Holloway had given a different answer?

Prometheus has its feminist themes, both in Weyland’s preferring his synthetic son to his real daughter, and in Shaw’s reprisal of A3’s refusal-of-motherhood theme, along with the medical device’s being programmed only for male patients. (This is also a class theme, since it’s really intended for just one male patient. But it does raise a loose end: what does Vickers think the machine is for? does she know it’s programmed only for men?)

The scene where the medical machine is used is incidentally one of the most memorable in the film. (And despite the superficial similarity, I don’t mean that in the same way that the maternity-ward scene is one of the most memorable in AVP:R; the AVP:R scene is just a cesspit of ugliness I can’t get out of my head, while the Prometheus scene, despite its likewise disturbing imagery, isn’t objectionable in the same way. Of course it helps that it’s a scene where the character is succeeding in taking control of her situation as best she can, rather than simply being gratuitously brutalised.) It certainly blows the scene with the New You machine from Logan’s Run out of the water.

The scene where Shaw attacks the medics is a nod to similar scenes with Ripley in the earlier films: a less violent one in A3, and an even more violent one in (the special edition of) Resurrection. David’s basketball shot is a nod to Ripley’s in Resurrection (which Weaver did perfectly on the first take). And in its ending narration, Prometheus echoes the ending narration of Alien, just as Aliens and A3 had.

Back in Part 1, I described Prometheus as one of the three most beautiful entries in the series. I’ll go farther: it is the most beautiful. Whatever its faults, the film is visually magnificent, with the opening footage of Iceland, the landing of the ship on LV-223, and the starmap inside the Engineer’s ship being standout examples. Its visual look and Fassbender’s performance are probably the two aspects of the film that will stay with viewers longest.

Wii the Living

The blu-ray will reportedly feature 20-30 minutes of extra footage, including a scene where David goes into Weyland’s dreams to receive his orders. Weyland is a young man in his dreams, which explains why they cast a young guy in old makeup rather than an actual old guy.

Before the film opened, three shorts were released. The first one features actually-young Weyland telling the legend of Prometheus, as well as the match story from Lawrence of Arabia again. (I wonder whether rentals of Lawrence have spiked as a result of this film?) This clip may or may not be a clue to the meaning of the film, though Weyland’s description of the eagle’s tearing through Prometheus’s belly is naturally going to remind viewers of the xenomorph birth process:

In this short, featuring Shaw, notice the reference to Yutani:

Finally, the best of the lot is this ad for the David-type of android. Note that David is the 8th model, just as Ripley was in Resurrection:

Two Robs In Peril

More juvenilia: “The Supersonic Nightingale” (retelling of Robin Hood legends, age 10) and “The Hole In the Sky” (short story, age 11).

For Whom An Alien Heat Makes Festival, Part 4: ALIEN VS. PREDATOR and ALIENS VS. PREDATOR: REQUIEM

SPOILER WARNING:

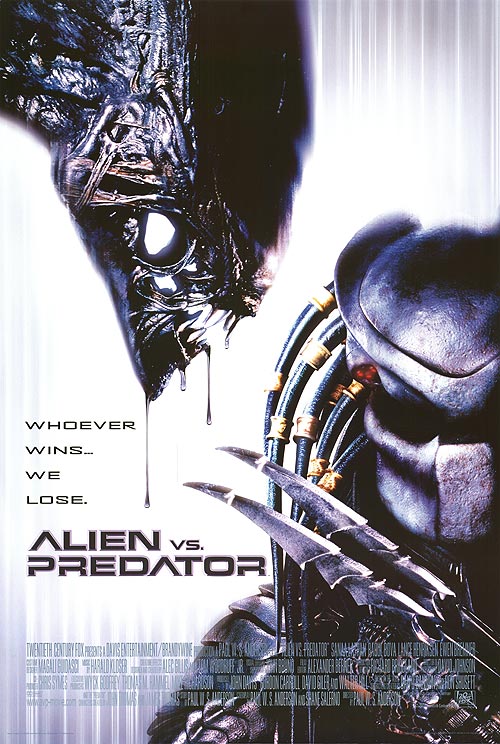

Alien vs. Predator (2004):

Let’s take some aliens that see only in infrared, and have them hunt another bunch of aliens that (as we were informed in Aliens) “don’t show up on infrared at all.” Yay that.

But is the title Alien vs. Predator, or AVP: Alien vs. Predator, or just AVP? Who cares, let’s call it AVP for short.

This is one of the ones I saw for the first time only recently. And although I hadn’t seen Prometheus when I watched this, I knew enough about Prometheus to be startled at the similarities between the two movies. Ridley Scott’s dismissal of AVP (he even claims never to have seen it, though he must surely be aware of the basic plotline) is ironic, since Prometheus seems to owe AVP a considerable debt. But more about that in Part 5.

AVP in turn owes a debt – acknowledged by the filmmakers – to H. P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness; both feature two races of aliens – one high-tech and somewhat human-relatable, the other a bunch of creepy monstrosities – fighting it out in an ancient underground structure in Antarctica. Lovecraft’s novel was in turn inspired by, and to some extent a sequel to, Edgar Allan Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, which has arguably also left its mark on AVP, as it features an underground structure on an Antarctic island whose mammoth inscriptions are a mixture of Egyptian, Ethiopian, and Arabic script. (Trivia fun: Jules Verne also wrote a sequel to Poe’s book.)

In AVP the three languages are Egyptian, Cambodian, and Aztec, and the theory is that the underground pyramid was built, under Predator supervision, by an ancient culture that was the predecessor of those three cultures. Hence its language was a blend of all three languages, which explains why the archeologists can decipher it.

I think I saw this place in Las Vegas

This is, if one is inclined to cavil, not enormously plausible. Archeologists and historians date the origins of recognisably Egyptian culture to several thousand years earlier than the other two; so the suggestion that they are all continuations of some earlier culture is a bit of a stretch. And the notion that a precursor language to Egyptian, Cambodian, and Aztec would be a mixture of readily recognisable symbols from each language betrays a curious view of linguistic evolution; it’s as though the common ancestor of apes and humans had one apish arm and one humanish arm. (Of course the temptation to link Egyptian with Aztec pyramids, and trace them to some sort of Atlantean and/or extraterrestial beginnings, is not exactly unprecedented in sf – the original Battlestar Galactica being a case in point. And in the interests of full disclosure, I wrote a comic book along similar lines as a teenager.)

But that’s hardly the only scientific howler in the film. My favourite is the archeologist who predicts that the pyramid – a labyrinth of constantly-shifting chambers, hallways, and death traps (basically Indiana Jones meets Cube) – will automatically reconfigure every ten minutes, because the Aztecs used base 10. No need to prove that the Aztecs used minutes, apparently. (And minutes aren’t an especially decimal unit ayway.)

There are continuity problems as well. Both of the previous Predator movies made a point of establishing that the Predators are partial to high-temperature climates, staying away from even normally warm regions except during extreme heat waves. So it’s a bit puzzling to see them strolling unperturbed around Antarctica. But then the same could be said of the humans – especially of the final scene with Woods standing in the bitter polar wind, hatless and jacketless, without a shiver.

Moreover, we’re told that the Predators have to lure humans into the pyramid as hosts for the xenomorphs: “Without humans, there could be no hunt.” Yet if, as we learned in A3, xenomorphs can gestate in nonhuman animals, why are humans needed? (Perhaps xenomorphs are smarter, and so more challenging prey, if they gestate in smarter organisms? I suppose that’s possible, though the one in A3 wasn’t exactly a pushover.)

Moving from plot holes to mere weaknesses: throughout the entire Alien series, the great fear has been the danger that the xenomorphs will make it to Earth, where they’ll be unstoppable. This concern is somewhat undermined by the revelation that Predators have been bringing xenomorphs to Earth for thousands of years. Admittedly, both AVP films portray the Predators as being careful to wipe out all traces of xenomorphs if they get loose – by detonating enormous explosions in AVP, and somewhat less reassuringly in AVP: Requiem by sending one guy with a bottle of blue acid to wander around in the sewers.

Woods and Stafford, dressed for cold weather but not for swarms of homicidal aliens

Still and all, AVP isn’t a terrible movie by any means. It’s visually striking, and clearly a labour of love filled with easy-to-miss fannish references. Sanaa Lathan’s Woods is evidently supposed to be a new Ripley – the savvy, competent woman whose authority keeps getting overridden by overconfident and/or panicked idiots doomed for death – though neither the script nor the actor is quite up to the considerable challenge of rivaling Ripley.

(You may recognise Colin Salmon, the actor who plays Stafford, Weyland’s right-hand man, as M’s right-hand man in the Brosnan Bond movies, and as Dr. Moon in Doctor Who.)

Charles Bishop Weyland himself, dying CEO of the company that will become Weyland-Yutani, and prototype for the Bishop series of androids in Aliens and A3, is a fairly effective character – more sympathetic and nuanced than previous company reps, and certainly more so than the cartoonish villains in Resurrection. The casting of Lance Henriksen provides a welcome a sense of continuity and familiarity: and in a nice nod to Aliens, his Weyland briefly, idly replicates Bishop’s “knife trick”:

The tag line for the film is, famously, “Whoever wins, we lose” (reportedly this is even what the Weyland satellite’s morse code signal is saying at the start of the film); but this is quickly subverted by the film’s actual plot, as should be no surprise given a few seconds’ thought.

Here comes Mama and she ain’t happy

The xenomorphs pose an existential threat to the entire human race; the Predators hunt singly or in small groups, and anyway have no interest in hunting their prey to extinction. The Predators have a sense of honour, or sportingness, or whatever you want to call it, which, while deeply screwed-up, puts some constraint on their destructiveness; it’s likewise possible in principle to avoid becoming their prey either by earning their respect (as Harrigan does at the end of Predator 2, or as Woods does here) or by falling beneath it (e.g., by being sickly or weaponless). By contrast, there is nothing one can do to be off a xenomorph’s kill list (except having a queen inside you, but that’s a suboptimal solution). Clearly the two groups are not comparable evils, and if one has to takes sides, it’s pretty obvious which side to take (as the protagonists quickly figure out).

The special edition dvd adds some good character moments and a brief glimpse of the earlier conflict that wiped out the whaling station in 1904. One striking revelation in the restored scenes is that the Predators in the film are teenagers and this is their ritual entrance to adulthood. I’ve gotta say, if fighting an army of xenomorphs in a deathtrap pyramid is their idea of an adulthood ritual, what the hell is picking off a few humans in a jungle – a cub scout entrance exam?

Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem (2007):

Because the film’s title is so often abbreviated AVP: Requiem or AVP:R, there’s some confusion as to whether the first word is “Alien” singular or “Aliens” plural. Even the insert sheet in the dvd case gets it wrong, giving it as the singular; but the title that actually appears onscreen promises us, accurately enough, Aliens plural versus Predator singular, so I’m going with that.  (Though whether “AVP:R” is also part of the title or merely the abbreviation is a topic on which I would not dare to speculate.) The “Requiem” of the title is also accurate, as the wretchedness of this film virtually ensured that there would be no more AVP films.

(Though whether “AVP:R” is also part of the title or merely the abbreviation is a topic on which I would not dare to speculate.) The “Requiem” of the title is also accurate, as the wretchedness of this film virtually ensured that there would be no more AVP films.

For this is indeed the worst of the ten films in this family of franchises. The two AVP movies are often lumped together as similar rubbish, but I find that unaccountable; the second one is a thousand times worse. (Exactly a thousand; I measured it with my agathometer.)

For one thing, it’s the least original of the lot; monsters-invade-a-small-town plots are a dime a dozen, and nothing new is done with that idea here. For another, it’s the most callous, mean-spirited, and pointlessly violent of the films, the one that veers closest to torture porn – with the scenes in the maternity ward being especially revolting and misogynistic. (What ultimately saves it from being torture porn is that the film’s attention span is too scattered to linger on any one scenario for more than a few moments.) For another, watching a lone Predator successfully taking down dozens of xenomorphs necessarily lowers the perceived threat posed by the latter, thus weakening audience investment.

Suboptimal bedside manner in the maternity ward

For yet another, many of the scenes are (famously) so dark that it’s difficult to see what’s happening; though that’s no great loss, as what we can see is, as previously noted, mostly repulsive and meaningless. Maybe the thought was that being unable to see would make it scarier, like being lost in the dark; but instead it just makes your attention shift away from the now invisible world of the film to the now more visible – and unless you’re unlucky, less frightening – world of your factual surroundings. Consequently the film oscillates between ill-lit boredom and better-lit revulsion, but with few actual scares.

At one point a character’s suddenly being attacked is clearly meant to be a surprise; yet when you see him just standing there in the doorway, it’s as though he had the words “cue xenomorph” tattooed on his forehead. There are similar scenes in the other films, but none as unsuccessful as this.

I’m told that the only things that can make AVP:R look good are the Asylum ripoff AVH: Alien vs. Hunter and the Sushi Typhoon (I am not making up the studio’s name) ripoff AVN: Alien vs. Ninja. I haven’t tested this claim empirically, but I suspect it is true; I gather that the latter movie makes the xenomorph a master of kung fu, because, um.

In fairness, AVP:R has a couple of semi-decent moments, as in these mildly amusing exchanges (paraphrased from memory):

– The colonel is lying to us,

– That’s crazy, the government doesn’t lie to people!– Whatever happens, we need to protect Kelly.

– What is this, the Titanic? Women and children first? Screw that shit, it’s every man for himself!

– She’s the only one who knows how to fly the helicopter. Unless you can. Otherwise shut the fuck up.

I just agreed to star in what?

The only slightly interesting character is Dallas, who shares his name with the captain of the Nostromo (and shares a line in common with Dutch in Predator). Yet he and Kelly actually represent a mixed-and-matched version of Ripley and Hicks (he’s a civilian, like Ripley [Ripley’s rank as lieutenant and/or warrant officer is clearly of the merchant-marine rather than the military variety]; she’s a soldier, like Hicks, but protecting a daughter, like Ripley; like both Hicks and Ripley, they’re the only voices of competence and good sense among overconfident and/or panicked idiots). Dallas is also an ex-con, which might be interesting if we ever learned more about what crime he committed and why, or why the sheriff nevertheless seems to trust him. (His joke about looking for work at the bank might mean he’d committed bank robbery, but might instead just be a reference to the difficulty of a convicted felon’s getting a job at a bank.)

My dvd carries only the special edition, but does feature restored footage markers, thus enabling viewers to compare the theatrical and extended versions anyway. The only advantage of the special edition is a couple more brief scenes with Dallas; otherwise, as the back of the dvd case promises, the extra scenes just add “more blood … more guts … more gore!”

Okay, so with AVP:R we’ve hit rock bottom. From here on there’s nowhere to go but up.

Next: Predators and Prometheus.

Two Brief Visions of the Future

More juvenilia: “World In the Wings” and “Letter from the Moon” (both age 12).

For Whom An Alien Heat Makes Festival, Part 3: ALIEN3 and ALIEN: RESURRECTION

SPOILER WARNING:

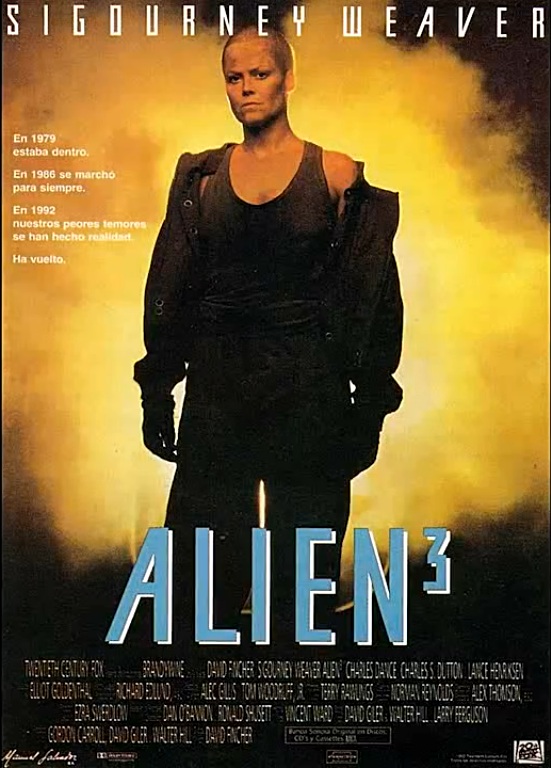

Alien3 (1992):

Now we come to the second of my “deviant” rankings. Just as I rank the original Predator rather lower than do most fans, I also rank Alien3 rather higher.

Let me begin by acknowledging that most of the standard fan complaints about A3 are quite legitimate. A3 takes the previous movie and stabs it in the gut – which, if you like Aliens (and you should), is distressing. Ripley’s victory at the end of Aliens is undercut when everyone she managed to save in the last movie, including her daughter surrogate, is killed off in the opening moments of A3 (thereby incidentally ejecting from the canon the intervening comics series detailing the adventures of the adult Newt) – and the triumphant ending of Aliens is replaced with a mood of bleak despair which sets in at the beginning of A3 and never really relents.

(How did the eggs get on the ship anyway? We can suppose that the xeno-queen laid them at the end of Aliens, but it doesn’t seem ever to have left the cargo bay, so how did its eggs end up so close to the cryotubes? And after everything that’s happened, wouldn’t Ripley have done a more careful search before bedding down?)

Moreover, in A3 Ripley’s character seems weakened in various ways. We learn that Ripley, who has heroically resisted alien penetration for the past two films, has been violated in her sleep and impregnated by a xenomorph, and thus is now also doomed to die; and she spends much of the film trying to get others to kill her before the “birth” does, because she lacks the courage to commit suicide. She is plunged into a misogynistic atmosphere and is on the verge of being gang-raped by several of the prisoners, and has to be rescued by a man. (It might have been more interesting if she’d been rescued by the xenomorph, protecting the bearer of the queen.) She has to share the screen with two compelling male characters (Clemens and Dillon) whose moral authority rivals hers. At one point she is offered leadership over the group, but makes no response, just sitting there listlessly, and someone else has to come up with the idea of luring the xenomorph into the furnace. And then Ripley dies at the end – which might seem like the ultimate defeat. Moreover, the fact that this is the first film in which she has sex (a sex scene between Ripley and Dallas was scripted for Alien but not shot; the relationship between Ripley and Hicks in Aliens becomes semi-flirtatious but never has time to develop), combined with her death at the end, raises the concern that she’s being made an instance of the misogynistic “Death by Sex” trope.

To these disadvantages of A3 we can add that an alien threat that refuses to harm the protagonist is not exactly going to make for the scariest entry in the series.

So yes, I grant the legitimacy of all these charges against A3. But that’s not the end of the story. So let me state my case for the film.

It’s always something

First, one of the positives of the Alien series is that unlike some series – I’m looking at you, Rocky, Rambo, Lethal Weapon, Friday the 13th, Die Hard, Fast and Furious, etc. – each film is thematically and tonally different from all the others. A3 could have been a jacked-up reprise of Aliens, with Ripley blowing away hordes of xenomorphs, but we already have Aliens; why not take the opportunity to do something different?

Second, recall that Aliens’ feminist credentials came at the cost of a feminist demerit: reinforcing the myth that courage, strength, and self-assertion in a woman are made possible and/or permissible only by the context, and in the service, of woman’s “natural role” of motherhood. In that respect, despite A3’s many feminist demerits, it gloriously subverts the previous film’s motherhood trope.

In A3, Ripley’s heroic struggle is a struggle not to reproduce, not to become a mother. Both the Weyland-Yutani company and the xenomorph regard Ripley as a mere shell or container for her potential offspring; they both value her highly, but only as a means of nurturance for the fetus inside her. As far as Ripley as a person in her own right is concerned, the company regards her as, in Ripley’s own words, “crud,” along with the prisoners the company has abandoned at the “ass-end of space.” But Ripley is willing to die rather than serve as an incubator for an unwanted fetus.

Possibly the brownest movie ever made

In short, Ripley’s position vis-à-vis both Weyland-Yutani and the xenomorph is quite strictly that of an unwillingly pregnant woman vis-à-vis the anti-abortion forces in society. A3 is a dramatisation of the pro-choice position.

(I remember that when the film first came out, a number of reviewers treated Ripley’s condition as a metaphor for AIDS, a far less precise analogy, and that nobody was making what seemed to me the obvious connection with the abortion issue. A quick google search on the keywords “Alien3” and “abortion” reveals that while the connection is made more often today – most recently at Daily Kos, of all places – it’s still not all that common, and in fact many of the results were simply people calling the film itself an abortion.)

Some will object, no doubt, that insofar as A3 is a pro-choice fable, it distorts the natural relationship of pregnancy; John Wilcox, analogously, has criticised Thomson-style defenses of abortion for treating “nature as demonic.” But nature in the merely biological sense is demonic when it threatens nature in the sense of full autonomous personhood – and social institutions are likewise demonic when they side with biology against personhood. As I have written elsewhere:

Opponents of the right to abortion find [Thomson-style arguments] repellent. How, they ask, can one treat a fetus as some sort of alien parasite, and pregnancy as a unnatural violation, when pregnancy is the most natural thing in the world? Well, sexual intercourse is also the most “natural” thing in the world; but when it is involuntary, it becomes rape. Likewise, when the “natural” process of pregnancy is involuntary, it too becomes an alien intrusion or violation.

Ripley’s suicide is no self-sacrifice, except in the merely biological sense; defying both the corporate/governmental forces outside her and the demonic nature within her, Ripley sacrifices herself-as-meat in order to honour herself-as-person. Ripley’s death is a victory (albeit under constrained circumstances), not a defeat.

Dillon and the Dead

The fact that the prisoners are described as double-Y chromosome cases, implying a genetic predisposition to aggression, raises a broader theme about whether biology is destiny – one that the redemption of (many of) the prisoners answers in the negative as much as does Ripley’s refusal of the reproductive role. (Incidentally it’s unclear whether Clemens is likewise supposed to be a double-Y case. His homicides were inadvertent rather than acts of deliberate violence, so it’s a bit odd that he was originally sent to this facility, and for a seven-year term, when the other inmates are described as incorrigibly violent, and as “lifers.” But then we never actually find out whether Clemens is telling the truth, though I’m inclined to think so.)

One might argue that Ripley is still filling a nurturing role, in that she is acting to protect the human race from the danger of xenomorph proliferation (no pun intended); but refusing to contribute to genocide seems more a matter of justice and integrity than of maternal care.

Nor do I think she is as effaced and defeated in the film as critics suggest. Yes, she has to share the screen with two powerful male personalities whose moral authority rivals hers; but, like Hicks, both acknowledge and reinforce her authority by granting her respect – Clemens immediately and willingly, Dillon later and grudgingly. (And Morse and Aaron still later and even more grudgingly.) Yes, she fails to accept, or even respond to, the offer of leadership; but the fact that it is even made, by the very same men who were previously mocking or threatening her, is another acknowledging of her authority. And Ripley holds her own against Dillon; when he warns her not to sit at his table because he is a “murderer and rapist of women,” she says something like “then I guess I must make you uncomfortable,” and sits down anyway. (It must be said that Dillon reacts better to her doing so than Ripley did to Bishop’s presence at her table in the previous movie.)

Dillon, A3’s major black character, shares a name in common with Predator’s main black character; this may be a coincidence, but there are a couple of other similarities as well: each Dillon is the protagonist’s chief rival for authority, their relationship is somewhat hostile for a while before becoming more positive, and each Dillon dies semi-voluntarily in an effort to protect others. (That said, A3’s Dillon is obviously a much cooler character.)

The needle and the damage done

The interplay between Ripley & Clemens – the mutual trust, despite mutual wariness – is also nicely handled: his readily supporting her cholera story, her readily offering him her arm for his needle despite the account he’s just given her of having accidentally killed eleven patients by giving them the wrong injections (this last is a bit reminiscent of the story of Alexander of Macedon’s proving his trust for his physician by willingly drinking his medicine despite having just been warned to distrust the physician as a poisoner; there’s a similar scene toward the end of The Fountainhead, when Roark signs Wynand’s contract without reading it). Of course it doesn’t hurt to have Charles Dance – with his usual grace, subtlety, and riveting presence – in the role.

Back in Part 1, I described A3 as one of the three most beautiful films in the series, while noting that many fans regard it as the ugliest. I understand the latter judgment: the dominant colour is brown, the dominant mood is bleak, and most of the prisoners are filmed in such a way as to make them look as ugly as possible. But to me the rich brown colour of the film (maybe it’ll sound more artistic if we call it sepia) is reminiscent of the artwork of Rembrandt and Hugo, while the camera’s lovingly dwelling on the lit-to-seem-grotesque contours of the prisoners’ faces reminds me of Leonardo’s sketches. Take a look at some of these images and see if you don’t find them akin to the intensely atmospheric all-pervading brownness of the film:

Da Vinci – Sketches

Rembrandt – The Philosopher

Rembrandt – Self-Portrait

Hugo – The Gibbet

Hugo – The Tower

Incidentally, you don’t want to know what Hugo used to achieve his brown tints. (Notice how, by saying that, I simultaneously cause you to want to know – thus making the sentence false when it would have remained true if left unuttered – and cause you to know, thus satisfying the desire in the very act of stimulating it. How to do things with words, eh?)

Why yes, we’re Browncoats

A few other points:

We’re told that Dillon’s religion is a Christian one, but it doesn’t seem to have much doctrinal content. But then faith tends to be fairly contentless in Hollywood movies; the problem will be much worse in Prometheus.

A3 is the first film to establish that the appearance of the xenomorph is affected by that of the organism it gestates in – a fact which will later be exploited (if a murky shape in mostly impenetrable darkness counts as successful exploitation) in Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem.

In related news, Ripley’s xenobaby seems to have a far longer gestation than any we’ve previously seen – but perhaps that’s because queens are different.

The scene where Ripley mistakes a pipe for the xenomorph is presumably a nod to the scene near the end of Alien where she mistakes the xenomorph for a pipe. (Though in keeping with A3’s lower fright level, this is obviously a less scary mistake to make.)

Why is the term “robot” in the first movie replaced by “android” in the second, and “droid” here? We might chalk it up to changes of usage during the years between Ripley’s hypersleeps, but the time gap between Aliens and A3 doesn’t seem as long as the previous one, and moreover Ripley herself shifts her usage along with everyone else, without apparent prompting.

The differences between the theatrical and special editions of A3 are the most dramatic for any in the series:

In the theatrical version, Ripley is found, still in her cryotube, in the crashed escape pod; in the special edition, she’s found lying on the beach by Clemens, in a hauntingly, bleakly beautiful opening scene whose deletion is a mystery. In the theatrical version, the xenomorph gestates inside a dog; in the special edition, it gestates inside an ox (yet, in an unfortunate continuity glitch, the first prisoner to encounter the xenomorph still calls out to it, mistaking it for the missing dog, even though no dog has been established as missing in this version).

The restored opening

Paul McGann’s character, Golic, plays a larger role in the special edition. For Doctor Who fans it’s ironic enough to see McGann in the theatrical version, since this is precisely the kind of situation – a base under siege, run by an arrogant, closed-minded administrator – that the Doctor tends to show up in; but he’s not exactly his usual helpful self here. He’s even less helpful in the special edition, where he releases the xenomorph after the other convicts actually manage to trap it. Golic calls the xenomorph a “dragon,” and appears to worship it – which, given his prior Christian commitments, amounts to falling into Satan worship. Needless to say, this is not what the Doctor is supposed to do when he meets Satan.

There’s a dead Bishop on the landing!

In the special edition, when the human Bishop gets shot he exclaims, apparently to himself rather than to Ripley, “I’m not a droid!” – as though he’s surprised to learn that he’s been telling Ripley the truth. Has he never seen his own blood before? (Of course his not being an android gets retconned when we meet the original Bishop prototype in AVP, assuming that’s to be treated as canonical.) Also, as Ripley dives into the furnace, the xenobaby no longer bursts from her chest. I assume the suits insisted on a chestburster scene to satisfy presumed audience demands; but the scene is far better without it, for several reasons. It gives Ripley a more dignified (and certainly less painful) death; it enables her to avoid at least more of what she’s spent the whole movie trying to avoid; and it allows her to present a more Christ-like silhouette as she falls. Moreover, it makes Ripley’s sacrifice more meaningful; if the queen had really been that close to coming out, then the human(?) Bishop wouldn’t have had time to get Ripley to the operating room anyway, and so she would have lost nothing in turning down his offer. The decision surely caries more weight if the forgone alternative is a genuine possibility. (For similar reasons, I think it would have been better had it been left ambiguous whether Bishop is lying or not; we would still presume that he probably is, but the possibility that he might be telling the truth would make Ripley’s decision riskier and thus more courageous.)

Falling toward apotheosis

On the dvd the sound quality is poor in some of the restored scenes; I gather that this has been cleaned up on the blu-ray, but I don’t (yet) blu-ray.

Alien: Resurrection (1997):

And now we pass from the five movies I’d seen when they first came out to the five movies I’ve just seen for the first time in the past two months.

Just as Alien3’s reputation suffers thanks to its radical tonal difference from Aliens, so likewise Alien: Resurrection’s reputation suffers thanks to its radical tonal difference from Alien3. Unfortunately, here the similarity ends. When viewed as films in their own right rather than as continuations of a franchise, A3 does very well, while Resurrection falters and flails.

One problem is the villains. I’m all for depictions of governmental perfidy, but the malefactors here are so blatantly, maniacally, cartoonishly, over-the-top evil that there’s no nuance to them at all. The three main bad guys – Perez, Gediman, and Wren – seem to be playing their roles for laughs, constantly popping their eyes for no clear reason. It’s been rumoured that Whedon wrote the script as a comedy and the director ruined it by having the actors play it straight, but I find it hard to reconcile this diagnosis with the villains’ behaviour, since the actors seem, in an exact reversal, to be trying to milk laughs out of lines and scenes that offer none. After the depth and seriousness of A3, these panto antics are unbearable.

Giger’s original design

Another problem is the hybrid – the creature that arises from the blending of Ripley’s and the xeno-queen’s DNA. H.R. Giger’s original designs for Alien gave us a sleek, eerily menacing creature that danced on the knife edge between seductive and repellent; the hybrid is just butt-ugly. (Giger sued for not being credited in the film; if I’d been Giger I’d sooner have sued for being credited.) The film picks up the rejection-of-motherhood trope from A3, as Ripley is required to kill her own “offspring”; but we didn’t particularly need that story told again, and less well.

The hybrid – a face only a mother could love/kill

The film does have a few saving graces. One, of course, is, as always, Ripley herself. The way that Ripley is brought back, with memories more or less intact, is clever, and the idea that she now has a bit of xenomorph in her and vice versa is clever too, and enables Weaver to play the most badass, edgy, self-confident version of Ripley we’ve yet seen.

Another saving grace is admittedly more potential than actual: the crew of the Betty is clearly Whedon’s first draft of the crew of the Serenity. Johner in particular is essentially the same person as Jayne, though the other characters are more mix-and-match. Alas, the ascent from the first crew to the later one is steep; the Betty crew’s dialogue doesn’t sparkle the way the dialogue in Firefly does, and apart from Call they’re less sympathetic as characters (partly because they lack the failed-rebellion backstory, and partly because they’re even less morally fastidious as to what missions they’ll accept). Still, this is the closest we’ll ever get to Alien vs. Firefly.

ALIEN: RESURRECTION’s three clownish villains

There are some striking scenes: the scientists using pain buttons to “train” the xenomorphs; the way the xenomorphs escape; Ripley finding her previous clones. And in what is otherwise the least visually appealing of the Alien films, the underwater scene is pretty.

There’s also a nice slap against the left-conflationist/vulgar-liberal/left-cop-right-cop/Chomskyesque assumption that state power is more trustworthy than state-enabled business power: at one point Ripley is told something like “oh, you don’t have to worry now – it’s not the greedy Weyland-Yutani corporation running this project any more; now it’s the government and the military, so everything’s changed.” Ripley says, “I doubt it.”

The complicity of scientists in the military-industrial complex is also highlighted. It’s long been a common sf trope for scientists to insist on studying and/or seeking peaceful communication with a potential alien threat, and to dismiss worries that doing so is too risky, while the military are conversely eager to blow the aliens to bits; see, for example, the original (1951) versions of The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Thing From Another World (two films that pick opposite sides in that dispute). But here scientists and the military are allied in seeking to study the aliens in order to blow others to bits, and they are alike dismissive of concerns about risks; this is unfortunately a more accurate depiction of the usual relation between science and government. (If only unethical scientists always had bulging eyes and insane grimaces like the ones in this movie! It’d make them easier to spot.)

Do androids dream of electric sheep that burst out of people’s chests?

Androids have been undergoing some changes during Ripley’s snoozes. Back in Alien (and still farther “back” in Prometheus, evidently), androids could be ordered to harm humans. (Bishop blames Ash’s actions on a malfunction, but only on the basis of Burke’s underdescription of what happened; we have no reason to think Ash was doing anything but following orders.) Then by Bishop’s day, androids were programmed with Asimovian inhibitions. Now, apparently, androids (or some of them) have achieved free will, and are subject to neither sort of command, though such androids are likewise hunted down (by blade runners?). (Incidentally, a sign of Ripley’s – well, “Ripley’s” – character arc, and admittedly of the general shittiness of her life story, is that she goes from distrusting Bishop because he’s an android to declaring Call trustworthy because she’s not human.)

Please mess with Ripley

The special edition differs from the theatrical version most dramatically in its beginning and its ending (though it also has a bit more Ripley character material). The special edition opens with a close-up on what is apparently a snarling xenomorph’s jaws; then the camera pulls back to show that it is actually an ordinary-sized housefly (or some similar insect) with some xenomorph features. So is this supposed to be an accidental byproduct of the experiments depicted in the movie? We’re never told. Pulling farther back, we see a human worker squishing the fly and then flicking it against a window, where it goes splat. At this point anyone who’s seen the previous movies expects the fly’s acidic blood to melt a hole in the window – with catastrophic results, since it quickly becomes clear that this window is on a spaceship. That would also be a nice foreshadowing of the hybrid’s fate later in the film. But no, nothing happens – it’s just a dead bug. And the next scene is the cloning lab that was the first scene of the theatrical version. So what was the point? After the atmospheric beginnings of the first three Alien movies, this pointless triviality is especially disappointing.

The ending scene, by contrast, is improved in the special edition. In the theatrical version, the Betty is landing on Earth, and Call looks out the window and declares with surprise that it’s beautiful (which is indeed a bit of a surprise, since Johner has told us earlier that Earth is a “shithole”), but we never see anything. In the special edition, by contrast, the Betty lands on a devastated nuclear landscape that was once Paris, and nobody declares anything beautiful – which seems more appropriate. (You can see the special-edition beginning and ending here and here; embedding disabled, alas.)

Next: Alien vs. Predator and Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem.