One of the tragic aspects of the emancipation of the serfs in Russia in 1861 was that while the serfs gained their personal freedom, the land – their means of production and of life, their land was retained under the ownership of their feudal masters. The land should have gone to the serfs themselves, for under the homestead principle they had tilled the land and deserved its title. Furthermore, the serfs were entitled to a host of reparations from their masters for the centuries of oppression and exploitation. The fact that the land remained in the hands of the lords paved the way inexorably for the Bolshevik Revolution, since the revolution that had freed the serfs remained unfinished.

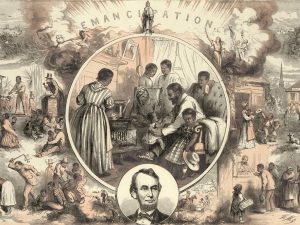

The same is true of the abolition of slavery in the United States. The slaves gained their freedom, it is true, but the land, the plantations that they had tilled and therefore deserved to own under the homestead principle, remained in the hands of their former masters. Furthermore, no reparations were granted the slaves for their oppression out of the hides of their masters. Hence the abolition of slavery remained unfinished, and the seeds of a new revolt have remained to intensify to the present day. Hence, the great importance of the shift in Negro demands from greater welfare handouts to “reparations”, reparations for the years of slavery and exploitation and for the failure to grant the Negroes their land, the failure to heed the Radical abolitionist’s call for “40 acres and a mule” to the former slaves. In many cases, moreover, the old plantations and the heirs and descendants of the former slaves can be identified, and the reparations can become highly specific indeed.