I confess to a certain Schadenfreude about this.

Archive | January, 2018

Like Noises in a Swound, Part 2

Some audiovisual supplements (not mine) to my San Diego trip:

Here’s the hotel where Liberty Fund put us up (and where my mother stayed in the 1930s):

This is what’s behind the hotel:

This is the Torrey Pines Reserve:

And this is my old Ocean Beach neighbourhood (where I first discovered comic books, back in the early 1970s):

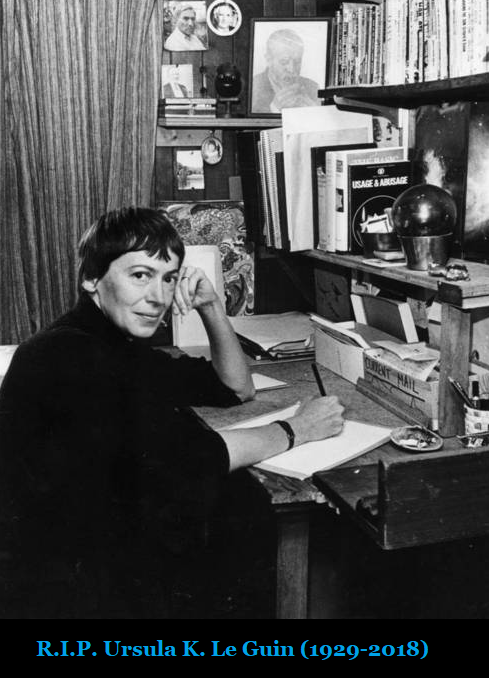

R.I.P. Ursula K. Le Guin

Like Noises in a Swound

I’m back from a Liberty Fund in San Diego (organised by Matt Zwolinski on Lysander Spooner). But I almost didn’t make it.

Ontological caution on display

I was scheduled to take the shuttle bus from Auburn to the Atlanta airport on Thursday morning. But on Wednesday I got a call from the bus company saying that thanks to the ice storm they were cancelling their Thursday morning trips – and all trips Wednesday as well. I contacted the local taxi company, who said that for a whopping fee they’d drive me to the airport, but only if we could leave right away (i.e., before they’d have to be driving in the dark, with colder temperatures and poorer visibility). So I frantically threw my clothes etc. into a suitcase, taking no time to shower, reserved a room for the night in Atlanta, and we were off. Between the traffic slowdowns, partial road closures, and sliding around on the ice, the trip to the airport took four hours (as opposed to the usual hour and forty-five minutes). Happily, all went properly the next morning.

Owing mainly to my mother’s final illness, when she couldn’t realistically be left alone overnight, I haven’t been on a plane for nearly two years. Incredibly, airplane bathrooms seem to have gotten even smaller in the interval, which I wouldn’t have thought possible. I can’t imagine how disabled passengers manage.

Torrey Pines Nature Reserve

I grabbed lunch at Las Cuatro Milpas, widely reputed to be the best Mexican eatery in the city. I thought the burrito was a bit dry, but the taco was incredible.

The conference on Spooner was great, and San Diego was lovely as usual. Being back there was a poignant reminder of what life is like where the airport is right in town rather than nearly two hours away, and nothing is ever shut down on account of an ice storm. The conference was at La Jolla’s Colonial Hotel, where my mother lived during the 1930s.

During a conference break I headed up to the Torrey Pines Nature Reserve, which I hadn’t seen since I was around eight or nine. Still as beautiful as ever.

Addendum:

I forgot to mention I also stopped by my old Ocean Beach neighbourhood and had lunch at Hodad’s.

The Invisible East

In the 3rd edition of Classics of Philosophy – which is, ironically, one of the texts I’m using in my “Philosophy East and West” course – Louis Pojman and Lewis Vaughn write:

The first philosophers were Greeks of the sixth century B.C. living on the Ionian coast of the Aegean Sea, in Miletus, Colophon, Samos, and Ephesus. Other people in other cultures had wondered about these questions, but usually religious authority or myth had imposed an answer. … The Great Civilizations of Egypt, China, Assyria, Babylon, Israel, and Persia … had produced art and artifacts and government of advanced sorts, but nowhere, with the possible exception of India, was anything like philosophy or science developed. Ancient India was the closest civilization to produce philosophy, but it was always connected with religion, with the question of salvation or the escape from suffering. Ancient Chinese thought, led by Confucius (551-475 B.C.), had a deep ethical dimension. But no epistemology or formulated logic. (pp. 3-4)

Is this true?

The two earliest Upanishads – the Brihadaranyaka-upanishad and the Chhandogya-upanishad – are generally dated to the 7th century BCE or earlier. They contain clear examples of philosophical argumentation. So why don’t their authors – or the thinkers whose views they purport to record (e.g., Yajñavalka and Uddalaka) – count as Indian philosophers antecedent to the Greeks?

Apparently because their views were “connected with religion” and “the question of salvation.” Yet Classics of Philosophy contains writings by Augustine, Anselm, Maimonides, Aquinas, Pascal, and Kierkegaard – for all of whom philosophy was closely bound up with religious questions. If this connection doesn’t invalidate their claim to be philosophers, why does it invalidate the like claim of their Indian predecessors?

In any case, it is not even true that all early Indian philosophical thought is connected with religion. The Charvaka or Lokayata school, which was atheistic, materialistic, and hedonistic, is generally dated to the late 7th century BCE as well – thus again antedating the Greeks.

As for why the early Chinese thinkers are ruled out as philosophers, we’re told it’s because, although they had a “deep ethical dimension,” they had “no epistemology or formulated logic.” So epistemology and logic are philosophy but ethics is not?

And anyway it’s not true that early Chinese thought had no epistemology or formulated logic. Even if we leave aside the exploration of logical paradoxes by such thinkers as Zhuangzi, Hui Shi, and Gongsun Long, we have a pretty clear example of epistemology and formulated logic in the Mohist Canons.

Of course the Mohist Canons date to around the 3rd century BCE, so if Pojman and Vaughn are making only a claim of chronological priority, they’re entitled to dismiss them. But the tone of the passage certainly offers no hint that these Chinese and Indian traditions got more philosophical later. And the fact that no Indian or Chinese sources appear in an anthology titled Classics of Philosophy (rather than, say, Classics of Western Philosophy) suggests that they don’t regard even later Chinese and Indian thought as containing anything worthy of the status of philosophic classic. The sophisticated logical and epistemological debates among the Navya-Nyaya, Purva-Mimamsa, Vyakarana, and Sautrantika-Yogachara schools, for instance, count for nothing, apparently.

It was bad enough when Antony Flew ignorantly declared in 1971 that Eastern Philosophy contains no arguments, but this is the 21st century, for petesake.

Who Said This?

[The] whole doctrine [of laissez-faire] was founded on the complete impossibility of directing, by invariant rules and by continuous inspection, a multitude of transactions which by their immensity alone could not be fully known, and which, moreover, are continually dependent on a multitude of ever-changing circumstances which cannot be managed or even foreseen ….