I found this note while going through old papers:

“The question is how you can best deter illegal immigrants and continue our heritage of an open immigration policy.”

– INS commissioner Alan Nelson, quoted in the Christian Science Monitor, 12/17/84

I found this note while going through old papers:

“The question is how you can best deter illegal immigrants and continue our heritage of an open immigration policy.”

– INS commissioner Alan Nelson, quoted in the Christian Science Monitor, 12/17/84

Having fun on an outer space trip

with the Alien somewhere on the ship

I go to take a nap in bed

when I wake up something’s eating my head

Alien, you’re eating my leg

I fall on the floor and I’m dying

Alien, go back to your egg

I plead and I beg

go away, go away

– from a song I wrote in 1979 to the tune of

Simon & Garfunkel’s “Cecilia”

“It’s not as if anyone’s going to remember that critter once they’ve left the theater.”

– Robert Aldrich, in the interview that lost him the job as director of Alien

In preparation for Prometheus (which I saw the week before last), I’ve been watching, and/or rewatching, all the previous Alien films, as well as the Predator and Alien vs. Predator ones – not because I thought the latter would matter for the plot of Prometheus (after all, Ridley Scott has made clear that he doesn’t regard the AVP movies as canonical), but because they’re in some sense part of the same æsthetic universe (and boy, did that turn out to be right!). Up till now, although I’d had the dvds sitting around for a while, I’d seen only the first three Alien films (though not the special editions thereof) and the first two Predator films, so I had some catching up to do.

Now that I’ve seen all ten fairly recently, I thought I’d blog about them. These aren’t necessarily going to be full-fledged reviews, just some collections of thoughts.

Glancing around a few internet polls and review compilations, I gather that the movies (leaving out Prometheus) are widely ranked in roughly the following order, from most to least popular:

Aliens

Alien

Predator

Predators

Alien: Resurrection

Alien3

Predator 2

Alien vs. Predator

Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem

My own somewhat idiosyncratic (and certainly less well-ordered) ranking is a bit different:

Alien & Aliens (tied)

Alien3 & Prometheus (tied)

Predators

Alien: Resurrection

Alien vs. Predator

Predator 2

Predator

Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem

Probably the most controversial aspects of my ranking are the relatively high position of A3 and the relatively low position of the original Predator; more on these matters in later posts. (The Prometheus ranking is especially tentative, since I haven’t had as much time to reflect on it.)

The ten films separate naturally into pairs, so I’ll devote five posts to them, taking them in order of release date, starting with Alien and Aliens.

SPOILER WARNING:

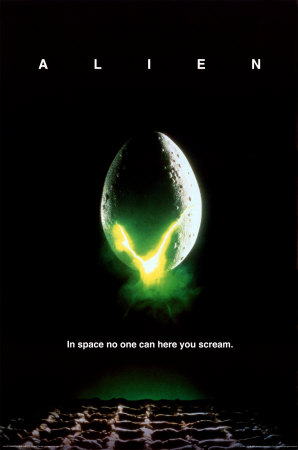

Alien (1979):

In space, no one can hear you scream. Unless you’re screaming on a spaceship with oxygen and other people.

I hadn’t seen Alien in its entirety since it was in theatres, when it was the first R-rated movie I’d seen. I went in fairly fully informed, as I’d read the comic book, and possibly the novelisation too, as well as the making-of coverage in Starlog. At the time I was struck by a) the haunting creepiness of the visuals and soundtrack during the opening credits (none of the later films has measured up in that respect), and b) the sleek menacing amazingness of the xenomorph itself, which aesthetically obsessed me for a while as I drew it over and over. (For simplicity’s sake I’m going to follow the fan habit of calling the creatures in the Alien series “xenomorphs,” even though the term just means any kind of extraterrestial life form; I’ll reserve “alien” for the broader meaning, covering both xenomorphs and Predators.)

This time around I was struck both by the superb, unhurried pacing and by just how generally beautiful the film is – one of the three most beautiful in the series, the other two being Alien3 and Prometheus. (I realise that for many viewers, Alien3 is by contrast the ugliest film in the series. I’ll return to this point in Part 3.) One of the most beautiful scenes is the one where Brett is looking for the cat – but finding the xenomorph – in a room with chains hanging from the ceiling, and water dripping (a scene echoed in the later films, but never as successfully). I have no idea what the chains or the water are for – dripping water is not generally the best way to maintain metal chains in good preservation, I suspect – but the effect is haunting. (I’d embed the clip but it doesn’t look nearly as good on YouTube as it does on the dvd.)

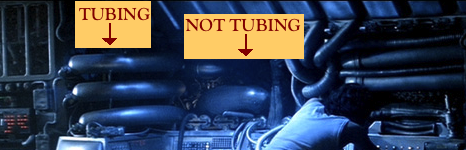

Another thing I noticed on this viewing is how, for the Earth tech in Alien, the film takes the basic spaceship look pioneered in their different ways by 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars, and tweaks it in an organic direction. Not anywhere near as organic as (what we may now call) the Engineers’ ship, of course, but subtly displaced in that direction; notice the quasi-organic bulges on the wall panels in the Nostromo. And notice also that the reason the xenomorph is able to hide in the shuttle at the end, initially unnoticed by Ripley, is that its head looks just like the tubing in the wall. (Imagine the xenomorph’s trying that in the bright white antiseptic interior of the Prometheus – though then again there seems to be no limit to what one can hide in the Prometheus.) Hence we can see continuity between the moderate organicism of the Nostromo and the extreme organicism of the Engineers’ ship; it’s as though the humans have already taken one step into the alien world from the start.

The plot with Ash also strikes me as borrowing from the HAL plot in 2001 – the A.I. with the hidden agenda and three-letter name who turns on the crew (even if David in Prometheus is more HAL-like in affect than Ash). And just as HAL is one letter backward from IBM (though the creators claim this is a coincidence), ASH is one letter backward from BTI, a prominent British computer company of the 1970s (though that may be a coincidence too). There’s even a very similar-looking scene in which Ripley, like Bowman, is trying to get through a door that Ash, like HAL, won’t open. Though alas, Ash doesn’t sing “Daisy” as he gets decapitated and incinerated. (The final shot of Ripley sleeping in her cryo-chamber also looks a bit like the final shot of Superbaby Bowman floating above earth.)

Don’t count on me, I Engineer

The film is not without flaws. In particular, there are some plot holes. How on earth, for example, can the Nostromo’s computer decode the Engineer’s signal? (Maybe Prometheus offers a possible answer to this question, but Prometheus wasn’t on the table at the time.) Also, in Marvel Comics there’s a famous puzzle about the Incredible Hulk: where does his extra mass come from when he transforms? In Alien, and indeed all the Alien movies, there’s a similar puzzle about the xenomorphs; how do they get so big, so fast? Given the live cocooning that they sometimes give their prey, we know that they don’t always eat what they catch; of course the cocooning isn’t shown in the first film (in the theatrical version, anyway) – but even before we knew about the cocooning, consider: between the time the tiny xenomorph bursts out of Kane’s chest and the time the now enormous xenomorph either kills or kidnaps Brett, no crew member has died; so it hasn’t gotten so large by eating the crew. Nor is there any mention of its having broken into ship’s stores to eat Weyland-Yutani’s version of MREs (which seem to consist largely of dodgy cornbread in any case). So where is it getting all those extra molecules? (This problem will assume particularly massive dimensions in Prometheus.)

Looking for Jonesy in all the wrong places

Moreover, the plot itself is not especially imaginative, since it’s essentially the standard hackneyed slasher-flick plot (lurking menace picks off the cast one by one, is thought defeated, until it suddenly and menacingly reemerges, before finally being finished off by the scantily-clad lone female survivor) – though admittedly this plot was not quite as hackneyed in 1979, when the Halloween franchise was only one movie old, while the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises were but gleams in their creators’ eyes and/or nostrils. (Alien has been accused of borrowing its main plot from a couple of episodes in A. E. van Vogt’s novel Voyage of the Space Beagle; see Wikipedia on the controversy. I wonder how successful Alien would have been if it had been titled Voyage of the Space Beagle. I realise it’s a reference to Darwin’s ship, but alas, that’s not the first image that “Space Beagle” brings to mind; I fear van Vogt must have had his mind in the null-A position when he chose that title. The working title of the film was Star Beast, which is better, but only just.)

Why is Ripley being mean to Bilbo?

On the other hand, the subplot with Ash and the Weyland-Yutani “crew expendable” directive adds another layer of complexity onto the basic plot – and sets a precedent: all the later movies add some degree of human perfidy, usually of the corporate and/or governmental variety, to the alien threat. (How much human perfidy Prometheus has depends on how much responsibility Weyland bears for David’s decisions.) But in the Alien movies, the villain is specifically the military-industrial complex, as Weyland-Yutani wants to use the xenomorph for its bioweapons division. (In the first film, the name is actually spelled “Weylan-Yutani,” but since the names were intended by the designer as references to Leyland and Toyota, and he actually refers to having gotten to “Weylan” from “Leyland” by “changing one letter,” I think it’s fair to treat “Weylan” as a typo for “Weyland,” as all the subsequent films have done.) Alien is also a rare case of a film set in outer space where the main characters are all working-class stiffs. (The name of the ship – as with Sulaco in the next film – is of course borrowed from Nostromo, Joseph Conrad’s novel of colonialism, exploitation, and corporate malfeasance.)

There is also, famously – and despite the final scene of Ripley being terrorised in her underwear – a feminist theme running through the film. On the one hand, the lead female character (a role originally scripted as male) is the most sensible and competent member of the crew, though her authority is constantly challenged and undermined by the others. On the other, the threat of rape and impregnation is no longer targeted specifically at women, but is expanded to include men – thus subverting a central trope of horror fiction.

The scene where Ripley refuses to let the infected Kane back on the ship is crucial to establishing her character. In a more traditional story it would be a male character taking the hardass position and a female character taking the sentimental but imprudent one – or if a woman did take the hardass position (even when it’s the obviously sensible position), she would thereby be identified by the script as an unsympathetic, overly “masculine” woman (as Vickers is in Prometheus). At this point in the story it’s not necessarily meant to be obvious to the viewer as yet that that’s not precisely what’s happening here too. Although in retrospect Ripley always seems central, by contrast with its successors Alien begins as an ensemble piece, with no one clear main character; the fact that she’s not with the team that explores the crashed ship may even serve to distract the audience’s attention from her importance. When the woman conventionally marked as unsympathetic and overly masculine emerges as the heroic protagonist – and not through being tamed and softened in the traditional narrative manner either – it’s a breath of fresh air, particularly in as traditionally male-oriented a genre as the big-budget science-fiction action film.

One of the great revelations of the film is of course Sigourney Weaver, in her first major movie role. (She’d been in Annie Hall, but playing a character listed only as “Alvy’s date outside theatre.” Remember her? Me neither.) Her performance is the steel spine running through the entire Alien series, and one of the many reasons (the others of course including scripts, direction, and design) that the Predator series has always been the weaker cousin, having never found as compelling a lead. (Hmm … Ripley/Ridley, what’s up with that?)

At one point the original script had called for the movie to end with the xenomorph’s biting Ripley’s head off and then making a radio transmission imitating her voice. I think we can all be grateful that option was dropped. (But it does foreshadow the voice-mimicking and higher intelligence of a different set of aliens in the Predator films, as well as of the T-1000 in Terminator 2.) Another early script had the xenomorph in the final scene become sexually attracted to Ripley, another idea well lost. (An early draft of Alien3 likewise had Ripley literally, sexually impregnated by the xenomorph. The bad ideas just won’t stop.)

The inclusion of Jonesy, the crew’s beloved cat, is also a nice touch, an invitation to shift perspective, since cats of course are ruthless and terrifying beasts of prey; the xenomorph is essentially a mouse’s-eye view of a cat.

My dvd set (the so-called Alien Quadrilogy, presumably on the theory that customers can’t grasp the word “tetralogy”) includes special editions of each film; in each case the special edition is an improvement. (I’ll use “special edition” as the generic term for director’s cuts, extended cuts, assembly cuts, unrated versions, et hoc genus omne.) In most cases the special edition is longer than the theatrical version, but not so in this case; yet it’s easier to identify what’s been added than what’s been removed, as the cuts mainly involved Ridley Scott’s shaving bits off here and there rather than deleting continuous chunks. One exception is the deletion of the scene where we learn that a) Ash was added at the last minute, at Weyland-Yutani’s insistence, to replace a different crew member, and b) Ripley doesn’t trust him. I can see why the scene was deleted, since (b) heightens audience suspicion of Ash too much, too soon; but it’s a pity that the information in (a) couldn’t have been incorporated at some point.

Of the restored scenes, one allows us actually to hear the Engineers’ eerie warning transmission; another has Ripley finding some of the missing crew members cocooned, and mercy-killing them (thus creating an inconsistency with Aliens, where Ripley says she’s never seen the cocooning before). (Some deleted scenes, included as dvd extras, are absent from both the theatrical and special editions.)

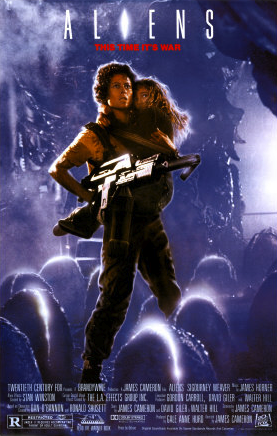

Aliens (1986):

Trivia fun: Aliens was not the first cinematic sequel to Alien; in between there was an unauthorised low-budget Italian followup, Alien 2: On Earth. (I haven’t seen it. I do not feel deprived.)

I have less to say about Aliens than I did about Alien. This is not to slight Aliens in any way; on the contrary, in many ways Aliens is an improvement over Alien. Admittedly the basic story situation isn’t especially innovative – it’s essentially what Doctor Who fans call a “base under siege” story (as A3 and Resurrection will be also). But Aliens complicates the base-under-siege plot in various ways; for one thing, it’s a base-under-siege story for only a relatively short, albeit narratively central, portion of the movie. The film breaks down into four parts: a) Ripley’s rescue and reawakening, and Weyland-Yutani’s dismissal of her story; b) Ripley’s return to LV-426 with the Marines, their initial encounter with the xenomorphs and rescue of Newt, and then being marooned on the planet; c) the “base under siege,” plus Burke’s sudden but inevitable betrayal; and finally d) Ripley’s return to the base to rescue Newt, followed by the duel with Xeno-Warrior-Queen on the shuttle.

Aliens expands Ripley’s role, explores her character in greater depth, gives her a more triumphant victory over the xenomorph (and over her own fear), and lets her engage in the kind of action-heroics usually reserved for male stars. The special edition also restores scenes revealing that Ripley’s daughter died of old age while Ripley was in cryogenic sleep – a fact that both heightens Ripley’s personal tragedy and explains her attachment to Newt. Weaver was understandably upset about the deletion of these character-rounding scenes, and it’s good to see them back. (In another restored scene, we see Newt’s family discovering the Engineers’ ship.)

Aliens also features a nice continuation of the political subtext about corporatism, with the government’s military apparently being put at the service of a private company; and James Cameron has noted that the soldiers’ initial swaggering overconfidence and subsequent panicked defeat was intended as a comment on the Vietnam war.

But from a feminist standpoint there’s a problematic aspect to Aliens as well, one not shared by the previous movie. As I noted a few months back whilst griping about the 2011 Doctor Who Christmas special:

The repeated message … that women’s strength comes from motherhood …. is one of the oldest arrows in patriarchy’s quiver. In a long literary tradition, a female character is most likely to be allowed to express strength and resolve if her doing so is somehow connected to her “natural” role as familial nurturer. Think of examples from Greek tragedy: Antigone and Electra, whose heroism is triggered by their feeling for a slain relative ….

The regrettable impression Aliens at least somewhat tends to create is that Ripley becomes an action hero, not because she is generally a courageous and resourceful person, but because the need to protect Newt has triggered her maternal instincts and flipped her into protective mama-bear mode; and the restored scenes about Ripley’s lost daughter, whatever their other virtues, only reinforce this impression – as does the implied parallel between Ripley and the xeno-queen, each fighting to protect her child(ren) from the other.

On the other hand, by granting Ripley the respect that no character evinced in Alien, Hicks and Bishop – not coincidentally the only two adult characters other than Ripley to survive the film’s events – somewhat redeem Aliens in this respect. (The subplot about Bishop’s overcoming Ripley’s anti-robot prejudice is another welcome complication to the story.)

At one point the marines’ dialogue suggests that humans have made contact (and even had sex) with intelligent extraterrestrials, specifically Arcturans, but this is never picked up on again, either in this film or in any subsequent one.

Aliens features a number of references designed for sf fans to pick up on: “drop ship” and “bug hunt” are nods to Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, the space station is named after Pohl’s Gateway, Bishop quotes Asimov’s laws of robotics, and Burke refers to a “Hyperdyne” robotics company reminiscent of Terminator’s Cyberdyne. And 57 years after the events of Alien, starship meal rations still feature an unappetising simulacrum of cornbread.

The movie also has a couple of plot problems, as this spoof points out:

Trivia fun: although they managed to make it look like dozens, the production crew for Aliens only had six xenomorphs to work with (just as Doctor Who’s first Dalek story had only four Daleks while trying to give the impression of a cityful).

Next: Predator and Predator 2.

How are philosophers and physicists alike?

They each think they’re working with the source code of the universe while everyone else is just clicking on pretty icons.

How are philosophers and physicists different?

The philosophers are right.