Beginning in the 1890s and continuing as far as the 1970s, a series of British pulp stories by various authors, collaborating in what nowadays would be called a “shared universe,” chronicled the adventures of a detective named Sexton Blake. The stories were broadly similar, I gather, to the Sherlock Holmes stories, though with more of a pulp/noir sensibility.

Beginning in the 1890s and continuing as far as the 1970s, a series of British pulp stories by various authors, collaborating in what nowadays would be called a “shared universe,” chronicled the adventures of a detective named Sexton Blake. The stories were broadly similar, I gather, to the Sherlock Holmes stories, though with more of a pulp/noir sensibility.

I say “I gather” because I haven’t read any of them. The Sexton Blake novels and magazines were marketed primarily to lending libraries, where much handling sped them to an early death; consequently they are quite rare today. (For more info on the stories see here, here, and here.)

One of the Sexton Blake authors, Anthony Skene (or, sometimes, Skeen; both were pennames of George Norman Philips, and no relation to the later Anthony Skene who wrote for The Prisoner, the Jeremy Brett Sherlock Holmes, and Upstairs, Downstairs), introduced what would become one of the series’ most popular characters – the exiled Serbian (or perhaps Romanian, or …) prince, Monseiur Zenith the Albino. Zenith essentially played the role of Moriarty to Blake’s Holmes – though with his violin-playing, opium habit, and code of honour he was a bit like Holmes himself, or perhaps a Holmes crossed with Dorian Gray, Rupert of Hentzau, and Francisco d’Anconia. There’s a long and dubious tradition of making albinos into sinister characters (it still continues today, in everything from The Da Vinci Code to Jonah Hex), but in Skene’s defense, this particular villainous albino is more admirable than not. Aristocratic, elegant, enigmatic, decadent, skillful, proud, fearless, with icy self-command and a streak of nobility, Zenith plays the role of master thief more for the fun of a dangerous game than out of avarice. Zenith easily stole all the scenes from the titular hero of the Blake stories, and was enough of a success that he could soon carry stories of his own.

One of the Sexton Blake authors, Anthony Skene (or, sometimes, Skeen; both were pennames of George Norman Philips, and no relation to the later Anthony Skene who wrote for The Prisoner, the Jeremy Brett Sherlock Holmes, and Upstairs, Downstairs), introduced what would become one of the series’ most popular characters – the exiled Serbian (or perhaps Romanian, or …) prince, Monseiur Zenith the Albino. Zenith essentially played the role of Moriarty to Blake’s Holmes – though with his violin-playing, opium habit, and code of honour he was a bit like Holmes himself, or perhaps a Holmes crossed with Dorian Gray, Rupert of Hentzau, and Francisco d’Anconia. There’s a long and dubious tradition of making albinos into sinister characters (it still continues today, in everything from The Da Vinci Code to Jonah Hex), but in Skene’s defense, this particular villainous albino is more admirable than not. Aristocratic, elegant, enigmatic, decadent, skillful, proud, fearless, with icy self-command and a streak of nobility, Zenith plays the role of master thief more for the fun of a dangerous game than out of avarice. Zenith easily stole all the scenes from the titular hero of the Blake stories, and was enough of a success that he could soon carry stories of his own.

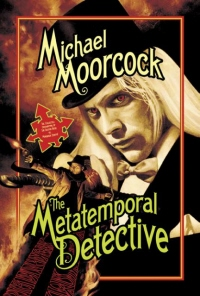

An early fan of, and indeed contributor to, the Sexton Blake series was the young Michael Moorcock, who has cited Zenith as a partial inspiration for his own most famous creation – the exiled albino prince Elric of Melniboné (though given that Elric is perpetually racked by guilt and self-doubt, while Zenith is nothing of the kind, I think Zenith may in some ways be an even closer inspiration for Huillam d’Averc, the languid, noble, deadly fop in Moorcock’s Hawkmoon books). Moorcock later went still farther, incorporating Monsieur Zenith himself into such works as Fabulous Harbours, War Amongst the Angels, Nomad of the Time Streams, The Metatemporal Detective, and Michael Moorcock’s Multiverse, setting him against a variant of Sexton Blake named Seaton Begg, and tying Zenith’s story in with those of Elric and the von Bek family. (Alan Moore, in turn, has included Zenith in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series.)

An early fan of, and indeed contributor to, the Sexton Blake series was the young Michael Moorcock, who has cited Zenith as a partial inspiration for his own most famous creation – the exiled albino prince Elric of Melniboné (though given that Elric is perpetually racked by guilt and self-doubt, while Zenith is nothing of the kind, I think Zenith may in some ways be an even closer inspiration for Huillam d’Averc, the languid, noble, deadly fop in Moorcock’s Hawkmoon books). Moorcock later went still farther, incorporating Monsieur Zenith himself into such works as Fabulous Harbours, War Amongst the Angels, Nomad of the Time Streams, The Metatemporal Detective, and Michael Moorcock’s Multiverse, setting him against a variant of Sexton Blake named Seaton Begg, and tying Zenith’s story in with those of Elric and the von Bek family. (Alan Moore, in turn, has included Zenith in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series.)

The popularity of Moorcock’s reimaginings of Zenith has sparked renewed interest in the original, making possible the lavishly illustrated reprinting of one of Skene’s standalone Zenith adventures (i.e., without Sexton Blake), simply titled Monsieur Zenith the Albino (1936), to which Moorcock has contributed an introduction rather like Alan Moore’s introduction to the new Elric series, i.e., a mixture of fact and fantasy. (Unwary readers may very well come to believe that Skene based Zenith on a real-life Count Rurik von Bek of Mirenburg.) Although published in 2001, the reprint already appears hard to get: Amazon US seems to think it’s out of print, and the lowest price it lists for a used copy is $366! Amazon UK, by contrast, treats it as in print (at a saner £23), but as on indefinite back order. It looks as though it may be possible to order it directly from the publisher here, though whether they have any currently in stock I don’t know.

The popularity of Moorcock’s reimaginings of Zenith has sparked renewed interest in the original, making possible the lavishly illustrated reprinting of one of Skene’s standalone Zenith adventures (i.e., without Sexton Blake), simply titled Monsieur Zenith the Albino (1936), to which Moorcock has contributed an introduction rather like Alan Moore’s introduction to the new Elric series, i.e., a mixture of fact and fantasy. (Unwary readers may very well come to believe that Skene based Zenith on a real-life Count Rurik von Bek of Mirenburg.) Although published in 2001, the reprint already appears hard to get: Amazon US seems to think it’s out of print, and the lowest price it lists for a used copy is $366! Amazon UK, by contrast, treats it as in print (at a saner £23), but as on indefinite back order. It looks as though it may be possible to order it directly from the publisher here, though whether they have any currently in stock I don’t know.

Anyway, I managed to find an affordable used copy online, and it’s terrific. Although I’m a Moorcock fan and came to Zenith via Moorcock, I have to say I prefer Skene’s version to Moorcock’s. I think Skene has created one of the great characters of popular fiction, and I earnestly hope that his other Zenith stories will eventually be reprinted also.

Anyway, I managed to find an affordable used copy online, and it’s terrific. Although I’m a Moorcock fan and came to Zenith via Moorcock, I have to say I prefer Skene’s version to Moorcock’s. I think Skene has created one of the great characters of popular fiction, and I earnestly hope that his other Zenith stories will eventually be reprinted also.

I’ve written before about Ayn Rand’s suggestion that the common literary phenomenon of a “fascinating villain or colorful rogue, who steals the story” represents an author’s (often unconscious) defiance of collectivist morality by granting to a criminal, an “eloquent symbol” of the “rebel as such,” the “fire of self-assertiveness” denied to the hero, thereby “dramatizing the conflict of independence versus conformity.” I feel fairly confident that Rand would have enjoyed this novel.