— Let’s see; I think ’tis now some seven o’clock,

And well we may come there by dinner-time.

— I dare assure you, sir, ’tis almost two,

And ’twill be supper-time ere you come there.

— It shall be seven ere I go to horse. …

It shall be what o’clock I say it is. …

Good Lord, how bright and goodly shines the moon!

— The moon? The sun! It is not moonlight now.

— I say it is the moon that shines so bright.

— I know it is the sun that shines so bright.

— Now by my mother’s son, and that’s myself,

It shall be moon, or star, or what I list,

Or ere I journey to your father’s house. …

— Forward, I pray, since we have come so far,

And be it moon, or sun, or what you please;

And if you please to call it a rush-candle,

Henceforth I vow it shall be so for me.

— I say it is the moon.

— I know it is the moon.

— Nay, then you lie; it is the blessed sun.

— Then, God be bless’d, it is the blessed sun;

But sun it is not, when you say it is not;

And the moon changes even as your mind.

What you will have it nam’d, even that it is,

And so it shall be so for Katherine.

(Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew)

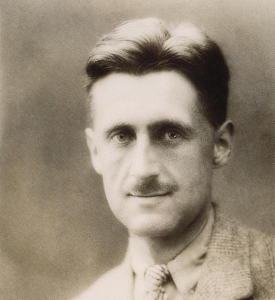

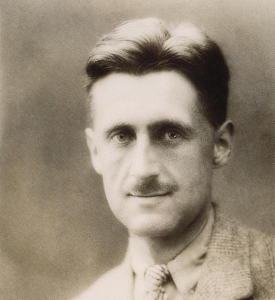

— How many fingers am I holding up, Winston?

— Four.

— And if the party says that it is not four but five – then how many?

— Four. …

— How many fingers am I holding up, Winston?

— I don’t know. I don’t know. You will kill me if you do that again. Four, five, six – in all honesty I don’t know.

— Better.

(George Orwell, Nineteen-Eighty-Four)

— How many lights do you see there?

— I see four lights.

— No, there are five. Are you quite sure?

— There are four lights. …

— I can produce pain in any part of your body at various levels of severity. Forgive me; I don’t enjoy this, but I must demonstrate. It will make everything clearer. …

— There … are … four … lights!

(“Chain of Command,” Star Trek: The Next Generation)

— Would you like some? I know they haven’t fed you since you got here. That’s at least two days. Besides, it’s lunchtime. Isn’t it? Isn’t it lunchtime?

— You just said it was morning.

— Well, you can’t have a corned-beef sandwich for breakfast. It would upset your stomach. Corned-beef sandwiches are for lunch. If it’s morning, you can’t have it. If it’s lunchtime you can. Is it lunchtime?

— I’m sure it’s lunchtime somewhere.

— Excellent answer. … It does prove, though, how everything is a matter of perspective. You think you see daylight, and you assume it’s morning. Take it away, you think it’s night. Offer you a sandwich: if it’s convenient, you’ll think it’s midday. The truth is fluid. The truth is subjective. Out there, it doesn’t matter what time it is. In here, it’s lunchtime if you and I decide that it is. The truth is sometimes what you believe it to be and other times what you decide it to be. My task is to make you decide to believe differently. And when that happens, the world will remake itself before your very eyes.

(“Intersections in Real Time,” Babylon 5)