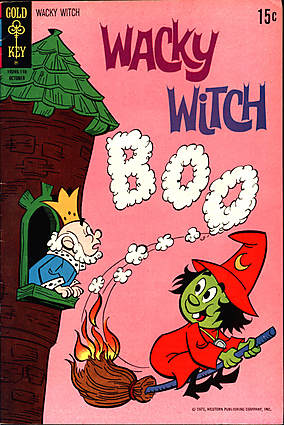

I recall a long car trip with my mother from Colorado Springs to San Diego when I was seven. (We were moving.) (I mean we were relocating to a different residence, not merely that we were in motion relative to our geographical surroundings.) The only reading material I seem to have had with me was a single comic book (Wacky Witch #4, October 1971 – this was before I’d discovered the greener pastures of superhero, sci-fi, and horror comics, a revelation awaiting me in the stores of Ocean Beach), and so I read its contents, aloud, in the car, over and over and over and over and over and over as we traversed the desert landscape. That my mother did not bludgeon me to death with the tire iron is a mystery that passeth understanding. (Maybe we didn’t have a tire iron?)

(I haven’t seen this issue in many years and have no idea whether I still even have it , but I can still assure you: show me a king who can’t sleep, and I’ll show you a sleepy king!)

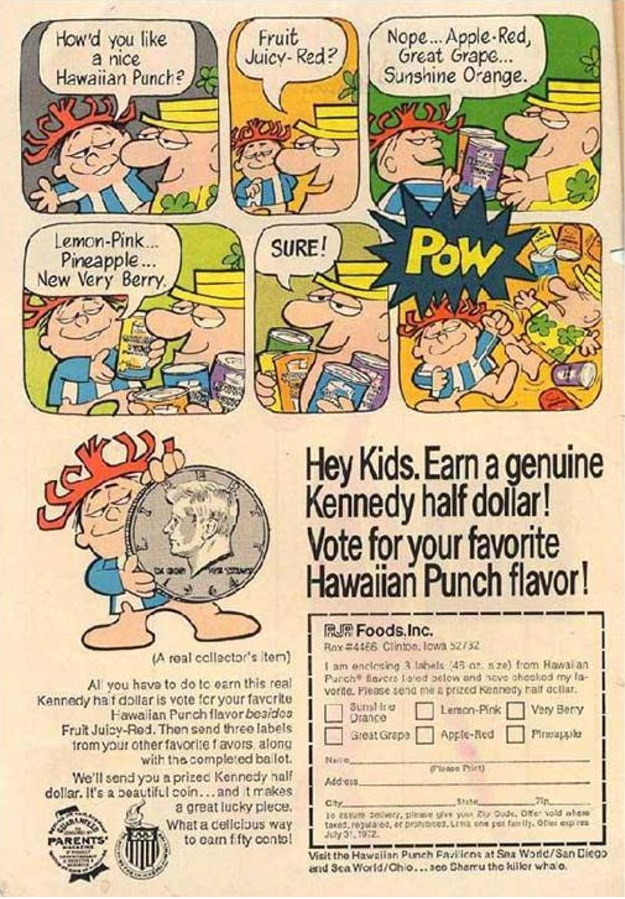

Anyway, my audio performance included not only the story but also, as an extra treat for my captive audience, the ads. There was one Hawaiian Punch ad that to this day I can still recite nearly verbatim – but I don’t need to, because I just found it online:

As a tot I found this very droll.

Anyway, back then I didn’t give much thought as to why Fruit Juicy Red was excluded from the promotion. (I remember a slight puzzlement, but no real interest in the question.) But now, knowing some economics, I would guess that Fruit Juicy Red was their best selling flavour, and that this promotion was designed to get readers to buy (or to nag their parents to buy) some of the other flavours as well – not to get them simply to switch from Fruit Juicy Red to another flavour (there’d be no particular point in achieving that), but rather on the hypothesis that if kids got to liking a wider variety of Hawaiian Punch flavours, this would lead to their desiring Hawaiian Punch more often (since if they got temporarily sick of flavour A they might then turn to flavour B of the same brand rather than turning to some entirely different brand), and so a greater total amount of Hawaiian Punch would be sold.

Incidentally, let me assure you, for the sake of my mother’s sanity, that the in-car entertainment on this cross-desert voyage did not consist solely in my repeated dramatic readings of Wacky Witch #4. My mother and I also improvised a long drama about two brothers, Maraschino (an aristocratic fop) and Bing (a crude, vulgar sort), though the details now escape me.