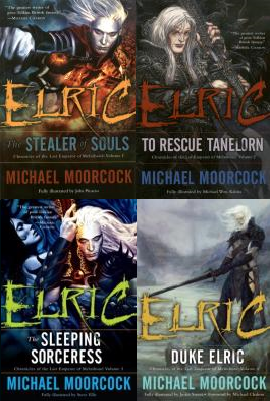

Inspired by the success of its recent Robert E. Howard collections (about which I’ve blogged previously), Del Rey is coming out with what’s being billed as the “definitive” collection of Michael Moorcock’s Elric stories in six volumes (four of which – Stealer of Souls, To Rescue Tanelorn, The Sleeping Sorceress, and Duke Elric – are now out, with the fifth due in October).

If you don’t know, Elric of Melniboné is the tormented albino prince, betrayer of his homeland and slayer of his kin, avatar of the Champion Eternal, who wanders in exile through a dream-haunted landscape, sustaining his feeble strength through a combination of drugs, sorcery, and a howling vampiric sword, forever doomed to serve as a pawn in the struggles between the supernatural forces of Law and Chaos. That guy.

If you don’t know, Elric of Melniboné is the tormented albino prince, betrayer of his homeland and slayer of his kin, avatar of the Champion Eternal, who wanders in exile through a dream-haunted landscape, sustaining his feeble strength through a combination of drugs, sorcery, and a howling vampiric sword, forever doomed to serve as a pawn in the struggles between the supernatural forces of Law and Chaos. That guy.

Like the Howard volumes, these are profusely illustrated (though not quite as profusely as the Howard), with lots of previously unpublished or otherwise hard-to-find extras (including maps, letters, magazine covers, comic book scripts, and the original short story on which the Erekosë novel The Eternal Champion was based); and, again like the Howard series, the stories are being presented (in theory – more on this below) in the order they were published rather than, as in previous collections, in the order of internal narrative chronology. (It makes a big difference, since Moorcock improvidently killed Elric off three years after he introduced him, thus requiring all subsequent Elric stories to be prequels.)

Any serious Moorcock fan will want to pick these up. But is this really the “definitive” Elric collection? Surely not – since, for one thing, it’s not complete, as they’re not planning to include Return to Melniboné, Dreamthief’s Daughter, The Skrayling Tree, The White Wolf’s Son, or The Metatemporal Detective. But in any case Moorcock has rewritten his stories so many times that it’s hard to say what would count as a definitive collection. In the case of “The Jade Man’s Eyes”/“Sailing to the Past,” one of the more drastically revised stories, this collection includes both versions; but in other cases it provides just one version (sometimes the original version, sometimes a revised one).

There are good reasons to provide the stories in the order they were published. For one thing, the earliest stories were written when Moorcock was in his early twenties; his writing has grown more sophisticated over the past four decades, and following internal chronology would require passing from the complex and nuanced prequels of his prime to the vigorous but less mature finale of his youth, which could render the reader’s experience of the latter anticlimactic. Moreover, the prequels often contain foreshadowings the enjoyment of which depends on having read Elric’s eventual fate.

There are good reasons to provide the stories in the order they were published. For one thing, the earliest stories were written when Moorcock was in his early twenties; his writing has grown more sophisticated over the past four decades, and following internal chronology would require passing from the complex and nuanced prequels of his prime to the vigorous but less mature finale of his youth, which could render the reader’s experience of the latter anticlimactic. Moreover, the prequels often contain foreshadowings the enjoyment of which depends on having read Elric’s eventual fate.

But there are problems with the order-of-publication approach also. One is that there are far more plot continuities from story to story in the Elric saga than in, say, Conan, so that jumping back and forth in time is more distracting (wait, this Theleb K’aarna guy is alive again now? have Elric and Rackhir met before or not?). But the other is that there really is no such thing as a clear “order of publication” any more, since Moorcock would often revise an earlier story to include references to later-written prequels (like George Lucas digitally inserting Hayden Christensen into the final scene of Return of the Jedi). For example, in the current versions of two of the very earliest Elric stories – “The Dreaming City” and “The Stealer of Souls” – Elric’s troublesome cousin Yyrkoon is described as having done a particular dastardly deed “twice” (p. 18) or “for the second time” (p. 95) – though as far as the presumably baffled reader knows, he’s only done it once. These are clearly revisions inserted to refer to events in the novel Elric of Melniboné, which was written after the stories but takes place before them – and which was apparently intended, at the time the revisions were made, to be read before them as well. So what counts as order of publication in this case? Clearly Moorcock’s stated goal of giving his readers “the nearest possible thing to the experience of the stories coming out for the first time” can’t be fully achieved as long as he’s including such revisions. (Yet one wouldn’t want them not included.)

On the other hand, thanks to various sorts of time-shifts, internal narrative chronology offers no stable order either; this is especially true in the crossover stories, where the irregularities of time across different dimensions mean that, e.g., Elric’s first meeting with Corum is Corum’s second meeting with Elric.

This whole question is to some extent moot, however, because the new collection does not really present the stories in order of publication anyway; since the stories are of such varying lengths, they’ve been moved around to reduce disparities in length among the volumes, with the result that story B sometimes comes before story A even when it is posterior to A in both narrative and publication chronology. A newcomer to Elric will thus sometimes be confused by the presentation here.

This whole question is to some extent moot, however, because the new collection does not really present the stories in order of publication anyway; since the stories are of such varying lengths, they’ve been moved around to reduce disparities in length among the volumes, with the result that story B sometimes comes before story A even when it is posterior to A in both narrative and publication chronology. A newcomer to Elric will thus sometimes be confused by the presentation here.

Still, to some extent it’s impossible to avoid such confusion, since Moorcock’s entire corpus of work, both within and beyond the Elric saga, is a moonbeam tangle of cross-references. “Elric at the End of Time,” for example, presupposes a number of non-Elric stories – not just the End of Time sequence but the Jerry Cornelius and Oswald Bastable stories as well. And who could possibly make sense of Duke Elric (or, albeit to a lesser extent, “The Black Blade’s Song”) without having read the non-Elric novel Blood? Thanks in part to all the revisions, everything in Moorcock’s fictional universe presupposes everything else, so there’s really no right place to start; one just has to jump in and try to catch up.

Since neither definitive contents nor a definitive order is perfectly possible with the Elric stories, I can’t really complain that this “definitive” edition isn’t truly definitive. Nothing could be so except a massive academic compendium chronicling every word of every version of everything Moorcock has ever written. (Which I would buy!) What matters is that the Del Rey collection is cool.

Let me close by quoting this delightful passage from the series introduction by Alan Moore (Moorcock’s fellow bushy-bearded cantankerous British anarchist fantasist):

I remember Melniboné. Not the empire, obviously, but its aftermath, its debris: mangled scraps of silver filigree from brooch or breastplate, tatters of checked silk accumulating in the gutters of the Tottenham Court Road. Exquisite and depraved, Melnibonéan culture had been shattered by a grand catastrophe before recorded history began – probably some time during the mid-1940s – but its shards and relics and survivors were still evident in London’s tangled streets as late as 1968. You could still find reasonably priced bronzed effigies of Arioch amongst the stalls on Portobello Road, and when I interviewed Dave Brock of Hawkwind for the English music paper Sounds in 1981 he showed me the black runesword fragment he’d been using as a plectrum since the band’s first album. Though the cruel and glorious civilization of Melniboné was by then vanished as if it had never been, its flavours and its atmospheres endured, a perfume lingering for decades in the basements and back alleys of the capital. Even the empire’s laid-off gods and demons were effectively absorbed into the ordinary British social structure; its Law Lords rapidly became a cornerstone of the judicial system while its Chaos Lords went, for the most part, into industry or government. Former Melnibonéan Lord of Chaos Sir Giles Pyaray, for instance, currently occupies a seat at the Department of Trade and Industry, while his company Pyaray Holdings has been recently awarded major contracts as a part of the ongoing reconstruction of Iraq.

Despite Melniboné’s pervasive influence, however, you will find few public figures ready to acknowledge their huge debt to this all-but-forgotten world, perhaps because the willful decadence and tortured romance that Melniboné exemplified has fallen out of favour with the resolutely medieval world-view we embrace today throughout the globe’s foremost neoconservative theocracies. Just as with the visitor’s centres serving the Grand Canyon that have been instructed to remove all reference to the caynon’s geologic age lest they offend creationists, so too has any evidence for the existence of Melniboné apparently been stricken from the record. With its central governmental district renamed Marylebone and its distinctive azure ceremonial tartans sold off in job lots to boutiques in the King’s Road, it’s entirely possible that those of my own post-war generation might have never heard about Melniboné were it not for allusions found in the supposedly fictitious works of the great London writer Michael Moorcock. …

Despite what the subtitle “The Complete Motion Comic,” along with the tag line “The Entire Watchmen Graphic Novel Comes to Life,” might lead one to believe, this is not complete; it’s radically abridged. Which is a shame, because I’d love to see the entire comic done this way.

Amazon.com recently started tagging gay-themed books as “adult,” meaning they’re removed from sales rankings and don’t show up in general searches. (Conical hat tip to

Amazon.com recently started tagging gay-themed books as “adult,” meaning they’re removed from sales rankings and don’t show up in general searches. (Conical hat tip to