In a passage that ended up being cut from Galt’s speech, Rand writes:

Man is an entity of mind and body, an indivisible union of two elements: of consciousness and matter. Matter is that which one perceives, consciousness is that which perceives it; your fundamental act of perception is an indivisible whole consisting of both ….Your consciousness is that which you know – and are alone to know – by direct perception. It is that indivisible unit where knowledge and being are one, it is your “I,” it is the self which distinguishes you from all else in the universe. No consciousness can perceive another consciousness, only the results of its actions on material forms, since only matter is an object of perception, and consciousness is the subject, perceivable by its nature only to itself. To perceive the consciousness, the “I,” of another would mean to become that other “I” – a contradiction in terms; to speak of souls perceiving one another is a denial of your “I,” of perception, of consciousness, of matter. (Journals of Ayn Rand, p. 663)

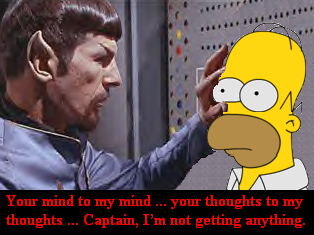

I think this is partly right and partly wrong. It’s wrong, I claim, to say that we can’t perceive other people’s consciousness directly. I’m not talking about telepathy, just the ordinary way that we perceive that someone is angry or bored or scared.

When I say that our awareness of other people’s states of mind is (often) direct, I mean, of course, epistemically direct – that is, not inferred from some other known fact. I don’t mean to deny that causally the chain between your anger and my awareness of it is indirect and quite complex; nor do I mean to deny that this awareness is made possible by additional background information I have accumulated. All I deny is that my awareness is inferred from any of these background factors. In short, what I claim about our direct perception of other people’s minds is very similar to what Rand claims about our direct perception of other people’s bodies.

When I say that our awareness of other people’s states of mind is (often) direct, I mean, of course, epistemically direct – that is, not inferred from some other known fact. I don’t mean to deny that causally the chain between your anger and my awareness of it is indirect and quite complex; nor do I mean to deny that this awareness is made possible by additional background information I have accumulated. All I deny is that my awareness is inferred from any of these background factors. In short, what I claim about our direct perception of other people’s minds is very similar to what Rand claims about our direct perception of other people’s bodies.

Rand might object that awareness of other people’s mental states is fallible while awareness of physical objects isn’t. But Rand doesn’t deny the existence of what would ordinarily be called perceptual illusions; she simply holds that in such cases what has occurred is either the mistaking of a perception of one thing for the perception of another, or else the mistaking of a perception for a nonperception. Now if Rand wants to use the term “perception” as a factive, that’s fine by me, but then I get to do the same thing; in that sense, perception of others’ consciousness is infallible too.

But the genuine truth that Rand is reaching for is that no one can be aware of my consciousness the way I am; I think she’s just confusing having a different mode of consciousness with having a different object of consciousness. There’s a way of being aware of X by being X, and no one but X can possess that form of awareness; here indeed “knowledge and being are one.” But what’s impossible is not perceiving the “I” of another, but perceiving it as one’s own “I.”

These issues are on my mind because in the department we’ve started a reading group on what looks so far to be an excellent book, Sebastian Rödl’s Self-Consciousness, which is trying to elucidate exactly what is involved in being aware of X by being X.

My very first publication, a 1992 book review of David Velleman’s Practical Reflection, is now online. It’s a bit more accessible to the non-philosopher than my Aristotle-on-relations review, but, well, not much.