[cross-posted at C4SS and BHL]

This month marks the 145th anniversary of the violent suppression of the Paris Commune by the French national government.

The Paris Commune remains a potent symbol for many people – though what exactly it symbolizes is a matter of dispute. To conservatives, the Commune stands for a reign of terror and mob rule. For many radicals, including anarchists and Marxists (even though at the time, Marx himself opposed the Commune as a “desperate folly” and urged would-be insurrectionists to work within the system), it signifies a community that importantly prefigures their own preferred social and political systems.

The Commune wasn’t quite any of these things. While it bears responsibility for some foolish decisions (such as trying to relieve bakers of their long hours by forbidding them to work at night, which is a bit like trying to cure a disease by punishing anyone who shows symptoms of it) and some wicked decisions (most notably, executing the noncombatant hostages), on the whole the Commune behaved in a rather moderate and restrained fashion, and was far from being the sanguinary monster of conservative nightmares. (To the Communards’ credit, they were reluctant to kill the hostages, and so waited until the last possible moment to do so. To their discredit, that means that by the time they did kill them, it was an act of pure spite that no longer had even the thin justification of a strategic purpose.) The invasion and massacre instituted by the national government at Versailles in May 1871 to put down the Communards’ insurrection has far more claim to be described as a reign of terror than anything the Commune itself did.

While it certainly has inspired anarchists and attracted their sympathy (Louise Michel being the most prominent anarchist figure to emerge from the movement), the Commune was not in any real sense an anarchist project. Yes, it was a working-class insurrection, but one aimed at establishing, and one that did in fact establish, a government. And unsurprisingly, that government did (as we’ve seen) some of the stupid and unjust things that governments tend to do (though the regime that ended up suppressing it was guilty of far worse).

Nor can the Marxists plausibly claim the Commune as a precursor. While generally statist-left-leaning in their policies, most leaders of the Commune had no interest in abolishing private property; as Marx himself noted, “the majority of the Commune was in no sense socialist.” The term “Commune” refers not to communism but to the independent mercantile cities, called “communes,” that flourished in Europe at the end of the medieval period. In that respect, the Paris Commune was fundamentally a secessionist movement; the Communards sought to make Paris into a self-governing political entity separate from the rest of France.

What anarchists tend to like about secessionist movements is their thrust toward political decentralization; what anarchists tend to dislike about them is their frequent concomitants of nationalism, parochialism, and isolationism. By those criteria, the Paris Commune scores fairly well, in that it did not seek to sever economic or cultural ties with the rest of the world; on the contrary, foreigners were eligible to be elected, and were in fact elected, to the governing council, on the theory that “the flag of the Commune is the flag of the World Republic.”

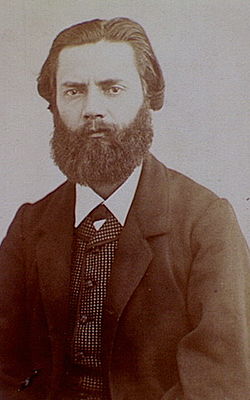

For all its flaws, the Paris Commune deserves anarchist respect as an example of cosmopolitan secessionism and working-class revolution. In honor of the Commune, I’ve translated “Paris, Free City,” a piece by Jules Vallès (1832-1885), one of the intellectual leaders of the Commune, from the early days of the rebellion’s initial success. It appeared in his periodical Le Cri du Peuple (“The Cry of the People”) on 22 March 1871. As will be apparent, Vallès is no anarchist; what anarchist could speak so cheerfully of “mayors [being] named and magistrates elected”? But in his secessionism, his enthusiasm for commerce, his distinction between an exploitative and a non-exploitative bourgeoisie, and his selecting the Hanseatic League as a model to emulate, he seems closer to anarchism – particularly market anarchism – than to Marxism.

Paris, Free City

There exists the working bourgeoisie and the parasitic bourgeoisie.

The one that the Cri du Peuple attacks, that its editors have consistently attacked and are still attacking, is the do-nothing one, the one that buys and sells positions and makes politics into a business.

A herd of windbags, a crowd of ambitious men, a breeding-ground for sub-prefects and state councilors.

The one, also, that that does not produce, that plunders; [The translation in Voices of the Paris Commune has: “They produce nothing but froth.” This is a misunderstanding of écumer, which in this context refers to piracy.] that raids, by means of shadowy banking schemes or shameless stock-market speculations, the profits made by those who bear the burdens — speculators without shame, who rob the poor and lend to kings, who played dice on the drum of Transnonain or 2 December, [The author refers to the massacre of insurgents by the National Guard in the Rue Transnonain on 14 April 1834, and Louis Napoléon’s bloody coup d’état on 2 December 1851.] and are already imagining how to play their hand upon the cadaver of the bloodied fatherland.

But there is a working bourgeoisie, this one honest and valiant; it goes down to the workshop wearing a cap, traipses in wooden shoes through the mud of factories, remains through cold and heat at its counter or its offices; in its small shop or its large factory, behind the windows of a shop or the walls of a manufactory: it inhales dust and smoke, skins and burns itself at the workbench or the forge, puts its hands to the work, has its eye on the task; it is, through its courage and even its anxieties, the sister of the proletariat.

For it has its anxieties, its risks of bankruptcy, its days when bills come due. There is not a fortune today that is secure, thanks precisely to the clumsiness and provocations of these parasites who need trouble and agitation to live. Nothing is stable: today’s boss becomes tomorrow’s heavy labourer, and graduates see their coats worn to rags.

How many I know, among the established or well dressed, who are beset by worries as the poor are, who sometimes wonder what will become of their children, and who would trade all their chances of happiness and gain for the certainty of a modest labour and an old age without tears!

It is this whole world of workers, fearing ruin or unemployment, that constitutes Paris – the great Paris. – Why should we not extend to one another our hands, above these miseries of man and citizen, and why, in this solemn moment, should we not try, once and for all, to wrest the country, where each is brother to the other through effort and danger, from this eternal uncertainty that allows adventurers always to succeed, and requires honest people always to tremble and suffer!

Fraternity was queen the other day before the cannons and under the bright sun. It must remain queen, and Paris must take a solemn decision – a decision that will be a good one, and will have its day in history, only if it avoids both civil war and the resumption of war against the victorious Bismarck. [Voices of the Paris Commune gets this precisely wrong: “if it manages to avoid civil war and returns to the war against the victorious Bismarck.” This is not a possible translation of si elle évite la guerre civile et le retour de la guerre avec Bismark vainqueur; besides, if Vallès were calling here for renewed conflict with Prussia, why would he be proposing to “submit to everything” in the next paragraph, and why would he be advocating a negotiated peace with the Prussians a few paragraphs later?]

We are prepared, for our part, to impose nothing, to submit to everything, within the dolorous circle of fatality – on the sole condition that the freedom of Paris remains safe, and that the flag of the Republic shelter, in an independent city, a courageous populace of workers.

Denizens of the working-class districts and bourgeois alike: a few hundred years ago, in the very Germany from which came the cannons that have thundered at us, four towns declared themselves free cities; [The four founding members of the Hanseatic League: Lübeck, Brunswick, Köln, and Danzig.] they were, for centuries, great and proud, rich and calm: in every corner of the world one could hear their activity, and they cast merchandise and gold on every shore! …..

Well then! to undo, other than by the sabre, the Gordian knot in which our recent misfortunes have been tangled, there is but one message to give:

PARIS, FREE CITY.

Let us negotiate immediately, through the intermediary of the elected representatives of the people, with the government of Versailles for the status quo without struggle, and with the Prussians for the settlement of indemnities.

No blood is shed, the cannons remain cold, the barracks close, and the workshops reopen, work resumes.

Work resumes! this is the inflexible necessity, the supreme desire. Let us come to an agreement in order that everyone, tomorrow, may recover his livelihood. Citizens of every class and every rank, this is salvation!

Paris, free city, returns to work.

This secession saves the provinces from their fear and the working-class districts from famine.

Bordeaux has said: Down with Paris!

We, for our part, cry at one and the same time: Long live France and long live Paris! and we commit ourselves never more to extend toward this France who calumniates us an arm that she believed to be menacing.

Between Montrouge and Montmartre [Southern and northern districts of Paris, respectively.] will always beat, come what may, the heart of the old fatherland, which we will always love, and which will return to us in spite of everything.

Moreover, some towns – precisely those that the moderates fear – will likewise be able to negotiate in order to live free, and to constitute the great federation of republican cities.

To those who fear that they should suffer from isolation, we respond that there are no frontiers high enough to prevent labour from crossing them, industry from razing them, commerce from boring through them.

Labour! – towns with high chimneys that spew the smoke of factories, with large workshops and long counters, fertile cities do not die! Even rustics would not kill their hens that lay golden eggs.

Paris, having a flag of her own, can no longer be defamed or menaced, and she remains the skillful seeker, the happy finder, who invents beautiful designs and great instruments, who will be forever implored to put her stamp on that this metal or that fabric, on this toy or that weapon, on this goblet or that basin, on the paste for a porcelain vessel or the silk for a gown!

She will remain the master and the king.

PARIS, FREE CITY.

No more bloodshed! rifles at rest: mayors are named and magistrates elected. And then to work! to work! The bell sounds for labour and not for combat.