It’s a privilege to inform you that the Molinari Society symposium on libertarianism and privilege will be in meeting room 402 (4th floor of the Marriott).

Be there or B2.

It’s a privilege to inform you that the Molinari Society symposium on libertarianism and privilege will be in meeting room 402 (4th floor of the Marriott).

Be there or B2.

[cross-posted at BHL]

A reminder for anyone planning to attend the American Philosophical Association in Philadelphia next week: here once again is the info on this year’s Molinari Society panel:

Eastern APA, Marriott Philadelphia Downtown, Monday, 29 December 2014:

Molinari Society, 1:30-4:30 p.m. [GIX-3, location TBA]:

Libertarianism and Privilegechair:

Roderick T. Long (Auburn University)presenters:

Billy Christmas (University of Manchester), “Privilege and Libertarianism”

Jennifer A. Baker (College of Charleston), “White Privilege and Virtue”

Jason Lee Byas (University of Oklahoma), “Supplying the Demand of Liberation: Markets as a Structural Check Against Domination”commentators:

Roderick T. Long (Auburn University)

Charles W. Johnson (Molinari Institute)

[cross-posted at BHL]

For some, especially on the right, reverse racism is just as serious and problematic as regular racism. For others, especially on the left, reverse racism is impossible; a black person, say, may be hostile toward or prejudiced against white people, but cannot count as racist toward them.

This disagreement is due, in part, to a further disagreement as to whether racism, and/or the badness of racism, is essentially a matter of individual attitudes and actions, or essentially a matter of systematic power relations. And the same issues arise with sexism, heterosexism, cissexism, and so on.

I think both sides are wrong. That is, I think reverse racism (along with sexism, etc.) is a) possible and real, but b) less seriously problematic than the regular sort. Let me say why.

I’ll start with a thought-experiment designed to convince those who already accept the existence of reverse racism (etc.) that it is less seriously problematic than the regular sort.

Thought-Experiment #1: Bobby Shafto’s Burger Shack

Bobby Shafto has an odd obsession with freckles, specifically facial freckles. He likes people with an even number of freckles on their face. (That includes people with no freckles on their face, since zero is an even number.) But he has an aversion toward people with an odd number of freckles on their face, and he refuses to allow them into his Burger Shack, either as employees or as customers. In his world, which we’ll suppose to be ours as well, Shafto’s particular prejudice is of course highly unusual. But on Twin Earth, let’s say, the same prejudice is widely shared among the even-freckled, and as the even-freckled command the lion’s share of economic and political power, they are able to make their prejudice effective.

Suppose Bobby Shafto and his odd discrimination policy really exist somewhere. We might well disapprove. But how concerned would we be about it? Not very, I suspect. And the reason isn’t hard to find: Shafto’s prejudice is so rare that it causes very little overall harm; it’s easy enough to find other places to work or to eat.

By contrast, when we consider the Twin-Earth scenario in which Shafto’s prejudice is the norm among those with economic and political power, then the life-choices of odd-freckled people would start to be systematically constrained, and the prejudice in question would begin to look like something in need of being condemned and combated in a serious and organised way. (Such combating need not necessarily take the form of legal coercion; but that’s a distinct issue.)

When I say that prejudice against odd-freckled people is a worse evil on Twin Earth than in our world, I don’t just mean that it has worse consequences (though that’s part of what I mean). I also mean that it evinces a worse motive and character – since it involves knowingly contributing to ongoing oppression, as Shafto’s does not.

So discrimination against the odd-freckled is a serious evil on Twin Earth; but our world is not Twin Earth. And considering Bobby Shafto in our world – Bobby Shafto the isolated eccentric weirdo – I ask those who think reverse racism is as seriously problematic as regular racism whether they also think Shafto’s discrimination policy is as seriously problematic as regular racism. If – as I predict – they mostly don’t, that would seem to show that they’re committed to acknowledging that the badness of racism is at least in large part a matter of the systematic constraining of people’s options – of their oppression, in Marilyn Frye’s sense. But that means that reverse racism – i.e., racism by an oppressed group against a non-oppressed group – cannot be as serious an evil as racism by a non-oppressed group against an oppressed group.

My argument presupposes, of course, that blacks are an oppressed group and that whites are not. (And ditto mutatis mutandis for women vs. men, etc.) Obviously some of the people who worry about reverse racism will deny that supposition. I think they’re crazy to deny it, but that’s a debate I’m not getting into here. For purposes of this post I’m addressing those who grant that blacks are oppressed while whites (quawhites) are not, but who nevertheless regard regular racism and reverse racism as equally bad. The point of my comparison between Bobby Shafto and Twin Earth is to convince holders of that position that they can’t hold it consistently.

Let me now turn to the second group – those who deny the possibility of reverse racism, on the grounds that racism is essentially about systematic , institutional oppression, not merely individual attitudes. The usual criticism of this view is that it conflicts with ordinary usage. That criticism is, I think, a strong one, but not quite as strong as its proponents suppose.

Why is the appeal to ordinary usage strong? Because the standard use of the word “racism” in ordinary language does treat individual attitudes as sufficient (even if not necessary) for racism. People are of course free to give the word “racism” a special sense as a technical term referring exclusively to institutional racism; but if that is all they are doing, then they are not entitled to criticise others who use the term in the ordinary way. By analogy, the term “trope,” as used in my profession, means something radically different from its use(s) almost everywhere else (whether in rhetoric, in literary theory, or in ordinary language); but it would be silly for me to criticise those who don’t use it as analytic philosophers do.

Why is the appeal to ordinary usage not necessarily decisive? Because a term’s ordinary use can legitimately be rejected if there turn out to be something wrong with that use – as I’ve argued is the case with, for example, the term “capitalism.”

But is there anything wrong with the ordinary meaning of “racism”? It allows for the possibility of reverse racism, of course, but is there anything wrong with doing so? One might think so, if one thought that acknowledging reverse racism as a category committed one to regarding reverse racism as comparable to regular racism either in extent or in moral seriousness; but no such commitment exists. (That the existence of reverse racism does not entail its being comparable in moral seriousness to regular racism was the moral of my Bobby Shafto thought-experiment above.) Of course the sort of people who tend to bang on about reverse racism do typically regard it as comparable, both in extent and in moral seriousness, to regular racism; but we do not need to deny the existence of a category in order to deny that the category has the significance that those who are most invested in the category generally attribute to it.

Another reason one might have for rejecting the ordinary meaning of “racism” is simply the need for a term that conveys the systematic, institutional dimensions of the problem; if “racism” as commonly used doesn’t do that, maybe we should change it so that it will. But in fact we have terms that do the trick, such as “oppression,” “white privilege,” and (mutatis mutandis) “patriarchy.” Those terms are all asymmetric; “racism” doesn’t need to be (nor, e.g., does “sexism”).

In any case, insisting that nothing counts as racism unless it involves systematic, institutional oppression has some consequences that even those who take that view ought to find awkward. This brings me to my second thought-experiment.

Thought-Experiment #2: Unfrozen Caveman Owner

Take someone you think is an obvious racist; presumably Donald Sterling will do (he’s also a sexist, so this example can do double duty), though pick someone else if you like. Now suppose that while touring a cryogenics facility he falls into the vat and is instantly frozen. When he is revived, many years (decades? centuries? millennia?) have passed, and he wakes into a world in which true racial (as well as gender, etc.) equality have finally been achieved. But all of Sterling’s attitudes remain the same as they were in the early 21st century. Is Sterling no longer a racist (and ditto for sexist)?

If racism necessarily involves society-wide power relations, then Sterling in my example is not a racist once he wakes up, since the power relations in question are gone. But it seems bizarre to deny that future-Sterling, with all his attitudes unchanged from those of present-Sterling, is a racist. I don’t just mean that it seems bizarre to me. Rather, I’m predicting (subject of course to falsification) that even those (or most of those) who are attracted to the denial of the possibility of reverse-racism will find it plausible to think of future-Sterling as a racist. But if he is a racist, then racism does not essentially depend on systematic oppression (even if much of racism’s moral interest stems from such oppression), and so the chief case against the possibility of reverse racism must be abandoned.

But perhaps it will be said that future-Sterling counts as a racist only because his beliefs and attitudes were formed in a social context of white privilege and so are still defined by their origin. Well in that case let’s consider a final thought-experiment.

Thought-Experiment #3: The Red and Yellow Peril

Two distinct ethnic groups, the Winkies and the Quadlings, live in adjacent territories. Each side regards the other as racially inferior degenerates who deserve to be either subjugated or exterminated. The two are at constant war with each other, but as they are roughly equally matched, neither side has succeeded in subduing the other. Are the Winkies and Quadlings not racist?

The mutual race hatred between the Winkies and the Quadlings seems like the kind of situation that the concept of “racism” is tailor-made to describe. But while each side seeks domination, neither has it. There’s no inequality, no privilege, no oppression. So racism, I suggest, need not involve these. In which case reverse racism is possible. Though not necessarily that big a deal.

[cross-posted at BHL]

Info on the next Molinari Society panel:

Eastern APA, Marriott Philadelphia Downtown, Monday, 29 December 2014:

Molinari Society, 1:30-4:30 p.m. [GIX-3, location TBA]:

Libertarianism and Privilegechair:

Roderick T. Long (Auburn University)presenters:

Billy Christmas (University of Manchester), “Privilege and Libertarianism”

Jennifer A. Baker (College of Charleston), “White Privilege and Virtue”

Jason Lee Byas (University of Oklahoma), “Supplying the Demand of Liberation: Markets as a Structural Check Against Domination”commentators:

Roderick T. Long (Auburn University)

Charles W. Johnson (Molinari Institute)

[cross-posted at BHL]

For various reasons (well, mainly money), the fourth issue of the Molinari Institute’s left-libertarian publication The Industrial Radical has been delayed for nearly a year; but today it is finally at the printer. Issue I.4 features articles by William Anderson, B-psycho, Jason Byas, Kevin Carson, Nathan Goodman, Irfan Khawaja, Tom Knapp, Smári McCarthy, Grant Mincy, Anna Morgenstern, Sheldon Richman, Amir Taaki, Mattheus von Guttenberg, Darian Worden, and your humble correspondent, on topics ranging from the Manning / Snowden whistleblower cases, the protests in Brazil, deference to authority, America’s foreign policy morass, Obama’s war on the environment, and the myth of 19th-century laissez-faire to alternative currencies, identity politics and intersectionality, abortion opponents as rape apologists, the Trayvon Martin / George Zimmerman case, the inside scoop on PorcFest, and why anarcho-capitalism cannot be a form of capitalism.

Issue 2.1 will follow soon thereafter, and we’ll be on an accelerated schedule until we’re caught up.

With each new issue published, we post the immediately preceding issue online. Hence a free pdf file of our third issue (Spring 2013) is now available here. (See the first and second issues also.)

Want to write for The Industrial Radical? See our information for authors and copyright policy.

Want to subscribe to The Industrial Radical? Visit our online shop.

Want to give an additional donation to the Molinari Institute? Contribute to our General Fund.

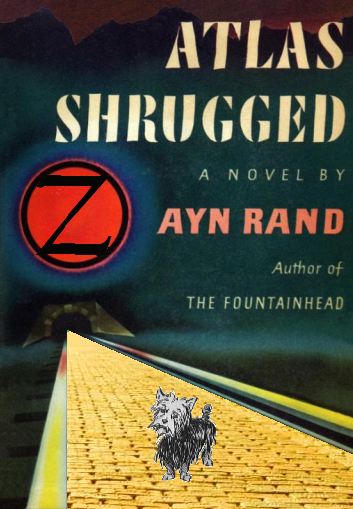

Ayn Rand, Iain Banks, J. R. R. Tolkien, Edgar Rice Burroughs, H. Rider Haggard, Nathaniel Hawthorne, C. S. Lewis, Frances Hodgson Burnett, and Dr. Seuss … in Oz!

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |