Nina Brewer-Davis contributes to the C4SS spontaneous order symposium.

Tag Archives | Feminism

Cordial and Sanguine, Part 37: When Spontaneous Orders Attack

Sometime BHL guest blogger Charles Johnson’s essay “Women and the Invisible Fist” is the first round in a Mutual Exchange on Spontaneous Order over at Center for a Stateless Society. Another essay by myself, followed by commentary on both essays from philosophers Nina Brewer-Davis, Reshef Agam-Segal, and David Gordon, will follow over the next couple of weeks.

One of Charles’ main themes is that the concept of spontaneous order (à la Hayek) is used ambiguously. Sometimes it means consensual rather than coercive order; sometimes it means polycentric or participatory rather than directive order; and sometimes it means emergent rather than consciously designed order.

What does that have to do with feminism, libertarianism, patriarchy, and rape culture? Find out.

Cordial and Sanguine, Part 36: Wedding Bells Are Joining Up That Old Gang of Mine

My review for Reason.com of Elizabeth Brake’s Minimizing Marriage: Marriage, Morality, and the Law is now online.

I’ve also blogged thereon at BHL.

But what I really want to know is: can I marry a corporation?

Unfree Minds, Unfree Markets

An interesting set of observations from dL on abortion, intellectual property, public goods, communitarianism, oligarchical collectivism, and the senses in which the u.s. government did or did not create the internet.

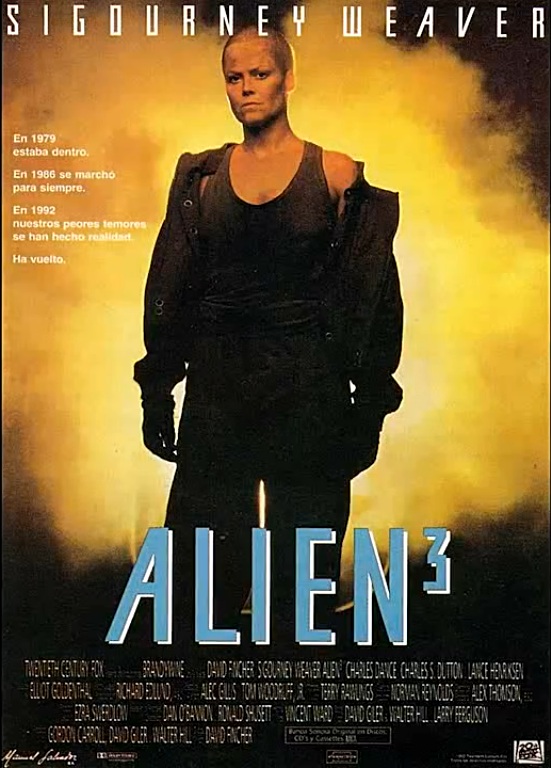

For Whom An Alien Heat Makes Festival, Part 3: ALIEN3 and ALIEN: RESURRECTION

SPOILER WARNING:

Alien3 (1992):

Now we come to the second of my “deviant” rankings. Just as I rank the original Predator rather lower than do most fans, I also rank Alien3 rather higher.

Let me begin by acknowledging that most of the standard fan complaints about A3 are quite legitimate. A3 takes the previous movie and stabs it in the gut – which, if you like Aliens (and you should), is distressing. Ripley’s victory at the end of Aliens is undercut when everyone she managed to save in the last movie, including her daughter surrogate, is killed off in the opening moments of A3 (thereby incidentally ejecting from the canon the intervening comics series detailing the adventures of the adult Newt) – and the triumphant ending of Aliens is replaced with a mood of bleak despair which sets in at the beginning of A3 and never really relents.

(How did the eggs get on the ship anyway? We can suppose that the xeno-queen laid them at the end of Aliens, but it doesn’t seem ever to have left the cargo bay, so how did its eggs end up so close to the cryotubes? And after everything that’s happened, wouldn’t Ripley have done a more careful search before bedding down?)

Moreover, in A3 Ripley’s character seems weakened in various ways. We learn that Ripley, who has heroically resisted alien penetration for the past two films, has been violated in her sleep and impregnated by a xenomorph, and thus is now also doomed to die; and she spends much of the film trying to get others to kill her before the “birth” does, because she lacks the courage to commit suicide. She is plunged into a misogynistic atmosphere and is on the verge of being gang-raped by several of the prisoners, and has to be rescued by a man. (It might have been more interesting if she’d been rescued by the xenomorph, protecting the bearer of the queen.) She has to share the screen with two compelling male characters (Clemens and Dillon) whose moral authority rivals hers. At one point she is offered leadership over the group, but makes no response, just sitting there listlessly, and someone else has to come up with the idea of luring the xenomorph into the furnace. And then Ripley dies at the end – which might seem like the ultimate defeat. Moreover, the fact that this is the first film in which she has sex (a sex scene between Ripley and Dallas was scripted for Alien but not shot; the relationship between Ripley and Hicks in Aliens becomes semi-flirtatious but never has time to develop), combined with her death at the end, raises the concern that she’s being made an instance of the misogynistic “Death by Sex” trope.

To these disadvantages of A3 we can add that an alien threat that refuses to harm the protagonist is not exactly going to make for the scariest entry in the series.

So yes, I grant the legitimacy of all these charges against A3. But that’s not the end of the story. So let me state my case for the film.

It’s always something

First, one of the positives of the Alien series is that unlike some series – I’m looking at you, Rocky, Rambo, Lethal Weapon, Friday the 13th, Die Hard, Fast and Furious, etc. – each film is thematically and tonally different from all the others. A3 could have been a jacked-up reprise of Aliens, with Ripley blowing away hordes of xenomorphs, but we already have Aliens; why not take the opportunity to do something different?

Second, recall that Aliens’ feminist credentials came at the cost of a feminist demerit: reinforcing the myth that courage, strength, and self-assertion in a woman are made possible and/or permissible only by the context, and in the service, of woman’s “natural role” of motherhood. In that respect, despite A3’s many feminist demerits, it gloriously subverts the previous film’s motherhood trope.

In A3, Ripley’s heroic struggle is a struggle not to reproduce, not to become a mother. Both the Weyland-Yutani company and the xenomorph regard Ripley as a mere shell or container for her potential offspring; they both value her highly, but only as a means of nurturance for the fetus inside her. As far as Ripley as a person in her own right is concerned, the company regards her as, in Ripley’s own words, “crud,” along with the prisoners the company has abandoned at the “ass-end of space.” But Ripley is willing to die rather than serve as an incubator for an unwanted fetus.

Possibly the brownest movie ever made

In short, Ripley’s position vis-à-vis both Weyland-Yutani and the xenomorph is quite strictly that of an unwillingly pregnant woman vis-à-vis the anti-abortion forces in society. A3 is a dramatisation of the pro-choice position.

(I remember that when the film first came out, a number of reviewers treated Ripley’s condition as a metaphor for AIDS, a far less precise analogy, and that nobody was making what seemed to me the obvious connection with the abortion issue. A quick google search on the keywords “Alien3” and “abortion” reveals that while the connection is made more often today – most recently at Daily Kos, of all places – it’s still not all that common, and in fact many of the results were simply people calling the film itself an abortion.)

Some will object, no doubt, that insofar as A3 is a pro-choice fable, it distorts the natural relationship of pregnancy; John Wilcox, analogously, has criticised Thomson-style defenses of abortion for treating “nature as demonic.” But nature in the merely biological sense is demonic when it threatens nature in the sense of full autonomous personhood – and social institutions are likewise demonic when they side with biology against personhood. As I have written elsewhere:

Opponents of the right to abortion find [Thomson-style arguments] repellent. How, they ask, can one treat a fetus as some sort of alien parasite, and pregnancy as a unnatural violation, when pregnancy is the most natural thing in the world? Well, sexual intercourse is also the most “natural” thing in the world; but when it is involuntary, it becomes rape. Likewise, when the “natural” process of pregnancy is involuntary, it too becomes an alien intrusion or violation.

Ripley’s suicide is no self-sacrifice, except in the merely biological sense; defying both the corporate/governmental forces outside her and the demonic nature within her, Ripley sacrifices herself-as-meat in order to honour herself-as-person. Ripley’s death is a victory (albeit under constrained circumstances), not a defeat.

Dillon and the Dead

The fact that the prisoners are described as double-Y chromosome cases, implying a genetic predisposition to aggression, raises a broader theme about whether biology is destiny – one that the redemption of (many of) the prisoners answers in the negative as much as does Ripley’s refusal of the reproductive role. (Incidentally it’s unclear whether Clemens is likewise supposed to be a double-Y case. His homicides were inadvertent rather than acts of deliberate violence, so it’s a bit odd that he was originally sent to this facility, and for a seven-year term, when the other inmates are described as incorrigibly violent, and as “lifers.” But then we never actually find out whether Clemens is telling the truth, though I’m inclined to think so.)

One might argue that Ripley is still filling a nurturing role, in that she is acting to protect the human race from the danger of xenomorph proliferation (no pun intended); but refusing to contribute to genocide seems more a matter of justice and integrity than of maternal care.

Nor do I think she is as effaced and defeated in the film as critics suggest. Yes, she has to share the screen with two powerful male personalities whose moral authority rivals hers; but, like Hicks, both acknowledge and reinforce her authority by granting her respect – Clemens immediately and willingly, Dillon later and grudgingly. (And Morse and Aaron still later and even more grudgingly.) Yes, she fails to accept, or even respond to, the offer of leadership; but the fact that it is even made, by the very same men who were previously mocking or threatening her, is another acknowledging of her authority. And Ripley holds her own against Dillon; when he warns her not to sit at his table because he is a “murderer and rapist of women,” she says something like “then I guess I must make you uncomfortable,” and sits down anyway. (It must be said that Dillon reacts better to her doing so than Ripley did to Bishop’s presence at her table in the previous movie.)

Dillon, A3’s major black character, shares a name in common with Predator’s main black character; this may be a coincidence, but there are a couple of other similarities as well: each Dillon is the protagonist’s chief rival for authority, their relationship is somewhat hostile for a while before becoming more positive, and each Dillon dies semi-voluntarily in an effort to protect others. (That said, A3’s Dillon is obviously a much cooler character.)

The needle and the damage done

The interplay between Ripley & Clemens – the mutual trust, despite mutual wariness – is also nicely handled: his readily supporting her cholera story, her readily offering him her arm for his needle despite the account he’s just given her of having accidentally killed eleven patients by giving them the wrong injections (this last is a bit reminiscent of the story of Alexander of Macedon’s proving his trust for his physician by willingly drinking his medicine despite having just been warned to distrust the physician as a poisoner; there’s a similar scene toward the end of The Fountainhead, when Roark signs Wynand’s contract without reading it). Of course it doesn’t hurt to have Charles Dance – with his usual grace, subtlety, and riveting presence – in the role.

Back in Part 1, I described A3 as one of the three most beautiful films in the series, while noting that many fans regard it as the ugliest. I understand the latter judgment: the dominant colour is brown, the dominant mood is bleak, and most of the prisoners are filmed in such a way as to make them look as ugly as possible. But to me the rich brown colour of the film (maybe it’ll sound more artistic if we call it sepia) is reminiscent of the artwork of Rembrandt and Hugo, while the camera’s lovingly dwelling on the lit-to-seem-grotesque contours of the prisoners’ faces reminds me of Leonardo’s sketches. Take a look at some of these images and see if you don’t find them akin to the intensely atmospheric all-pervading brownness of the film:

Da Vinci – Sketches

Rembrandt – The Philosopher

Rembrandt – Self-Portrait

Hugo – The Gibbet

Hugo – The Tower

Incidentally, you don’t want to know what Hugo used to achieve his brown tints. (Notice how, by saying that, I simultaneously cause you to want to know – thus making the sentence false when it would have remained true if left unuttered – and cause you to know, thus satisfying the desire in the very act of stimulating it. How to do things with words, eh?)

Why yes, we’re Browncoats

A few other points:

We’re told that Dillon’s religion is a Christian one, but it doesn’t seem to have much doctrinal content. But then faith tends to be fairly contentless in Hollywood movies; the problem will be much worse in Prometheus.

A3 is the first film to establish that the appearance of the xenomorph is affected by that of the organism it gestates in – a fact which will later be exploited (if a murky shape in mostly impenetrable darkness counts as successful exploitation) in Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem.

In related news, Ripley’s xenobaby seems to have a far longer gestation than any we’ve previously seen – but perhaps that’s because queens are different.

The scene where Ripley mistakes a pipe for the xenomorph is presumably a nod to the scene near the end of Alien where she mistakes the xenomorph for a pipe. (Though in keeping with A3’s lower fright level, this is obviously a less scary mistake to make.)

Why is the term “robot” in the first movie replaced by “android” in the second, and “droid” here? We might chalk it up to changes of usage during the years between Ripley’s hypersleeps, but the time gap between Aliens and A3 doesn’t seem as long as the previous one, and moreover Ripley herself shifts her usage along with everyone else, without apparent prompting.

The differences between the theatrical and special editions of A3 are the most dramatic for any in the series:

In the theatrical version, Ripley is found, still in her cryotube, in the crashed escape pod; in the special edition, she’s found lying on the beach by Clemens, in a hauntingly, bleakly beautiful opening scene whose deletion is a mystery. In the theatrical version, the xenomorph gestates inside a dog; in the special edition, it gestates inside an ox (yet, in an unfortunate continuity glitch, the first prisoner to encounter the xenomorph still calls out to it, mistaking it for the missing dog, even though no dog has been established as missing in this version).

The restored opening

Paul McGann’s character, Golic, plays a larger role in the special edition. For Doctor Who fans it’s ironic enough to see McGann in the theatrical version, since this is precisely the kind of situation – a base under siege, run by an arrogant, closed-minded administrator – that the Doctor tends to show up in; but he’s not exactly his usual helpful self here. He’s even less helpful in the special edition, where he releases the xenomorph after the other convicts actually manage to trap it. Golic calls the xenomorph a “dragon,” and appears to worship it – which, given his prior Christian commitments, amounts to falling into Satan worship. Needless to say, this is not what the Doctor is supposed to do when he meets Satan.

There’s a dead Bishop on the landing!

In the special edition, when the human Bishop gets shot he exclaims, apparently to himself rather than to Ripley, “I’m not a droid!” – as though he’s surprised to learn that he’s been telling Ripley the truth. Has he never seen his own blood before? (Of course his not being an android gets retconned when we meet the original Bishop prototype in AVP, assuming that’s to be treated as canonical.) Also, as Ripley dives into the furnace, the xenobaby no longer bursts from her chest. I assume the suits insisted on a chestburster scene to satisfy presumed audience demands; but the scene is far better without it, for several reasons. It gives Ripley a more dignified (and certainly less painful) death; it enables her to avoid at least more of what she’s spent the whole movie trying to avoid; and it allows her to present a more Christ-like silhouette as she falls. Moreover, it makes Ripley’s sacrifice more meaningful; if the queen had really been that close to coming out, then the human(?) Bishop wouldn’t have had time to get Ripley to the operating room anyway, and so she would have lost nothing in turning down his offer. The decision surely caries more weight if the forgone alternative is a genuine possibility. (For similar reasons, I think it would have been better had it been left ambiguous whether Bishop is lying or not; we would still presume that he probably is, but the possibility that he might be telling the truth would make Ripley’s decision riskier and thus more courageous.)

Falling toward apotheosis

On the dvd the sound quality is poor in some of the restored scenes; I gather that this has been cleaned up on the blu-ray, but I don’t (yet) blu-ray.

Alien: Resurrection (1997):

And now we pass from the five movies I’d seen when they first came out to the five movies I’ve just seen for the first time in the past two months.

Just as Alien3’s reputation suffers thanks to its radical tonal difference from Aliens, so likewise Alien: Resurrection’s reputation suffers thanks to its radical tonal difference from Alien3. Unfortunately, here the similarity ends. When viewed as films in their own right rather than as continuations of a franchise, A3 does very well, while Resurrection falters and flails.

One problem is the villains. I’m all for depictions of governmental perfidy, but the malefactors here are so blatantly, maniacally, cartoonishly, over-the-top evil that there’s no nuance to them at all. The three main bad guys – Perez, Gediman, and Wren – seem to be playing their roles for laughs, constantly popping their eyes for no clear reason. It’s been rumoured that Whedon wrote the script as a comedy and the director ruined it by having the actors play it straight, but I find it hard to reconcile this diagnosis with the villains’ behaviour, since the actors seem, in an exact reversal, to be trying to milk laughs out of lines and scenes that offer none. After the depth and seriousness of A3, these panto antics are unbearable.

Giger’s original design

Another problem is the hybrid – the creature that arises from the blending of Ripley’s and the xeno-queen’s DNA. H.R. Giger’s original designs for Alien gave us a sleek, eerily menacing creature that danced on the knife edge between seductive and repellent; the hybrid is just butt-ugly. (Giger sued for not being credited in the film; if I’d been Giger I’d sooner have sued for being credited.) The film picks up the rejection-of-motherhood trope from A3, as Ripley is required to kill her own “offspring”; but we didn’t particularly need that story told again, and less well.

The hybrid – a face only a mother could love/kill

The film does have a few saving graces. One, of course, is, as always, Ripley herself. The way that Ripley is brought back, with memories more or less intact, is clever, and the idea that she now has a bit of xenomorph in her and vice versa is clever too, and enables Weaver to play the most badass, edgy, self-confident version of Ripley we’ve yet seen.

Another saving grace is admittedly more potential than actual: the crew of the Betty is clearly Whedon’s first draft of the crew of the Serenity. Johner in particular is essentially the same person as Jayne, though the other characters are more mix-and-match. Alas, the ascent from the first crew to the later one is steep; the Betty crew’s dialogue doesn’t sparkle the way the dialogue in Firefly does, and apart from Call they’re less sympathetic as characters (partly because they lack the failed-rebellion backstory, and partly because they’re even less morally fastidious as to what missions they’ll accept). Still, this is the closest we’ll ever get to Alien vs. Firefly.

ALIEN: RESURRECTION’s three clownish villains

There are some striking scenes: the scientists using pain buttons to “train” the xenomorphs; the way the xenomorphs escape; Ripley finding her previous clones. And in what is otherwise the least visually appealing of the Alien films, the underwater scene is pretty.

There’s also a nice slap against the left-conflationist/vulgar-liberal/left-cop-right-cop/Chomskyesque assumption that state power is more trustworthy than state-enabled business power: at one point Ripley is told something like “oh, you don’t have to worry now – it’s not the greedy Weyland-Yutani corporation running this project any more; now it’s the government and the military, so everything’s changed.” Ripley says, “I doubt it.”

The complicity of scientists in the military-industrial complex is also highlighted. It’s long been a common sf trope for scientists to insist on studying and/or seeking peaceful communication with a potential alien threat, and to dismiss worries that doing so is too risky, while the military are conversely eager to blow the aliens to bits; see, for example, the original (1951) versions of The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Thing From Another World (two films that pick opposite sides in that dispute). But here scientists and the military are allied in seeking to study the aliens in order to blow others to bits, and they are alike dismissive of concerns about risks; this is unfortunately a more accurate depiction of the usual relation between science and government. (If only unethical scientists always had bulging eyes and insane grimaces like the ones in this movie! It’d make them easier to spot.)

Do androids dream of electric sheep that burst out of people’s chests?

Androids have been undergoing some changes during Ripley’s snoozes. Back in Alien (and still farther “back” in Prometheus, evidently), androids could be ordered to harm humans. (Bishop blames Ash’s actions on a malfunction, but only on the basis of Burke’s underdescription of what happened; we have no reason to think Ash was doing anything but following orders.) Then by Bishop’s day, androids were programmed with Asimovian inhibitions. Now, apparently, androids (or some of them) have achieved free will, and are subject to neither sort of command, though such androids are likewise hunted down (by blade runners?). (Incidentally, a sign of Ripley’s – well, “Ripley’s” – character arc, and admittedly of the general shittiness of her life story, is that she goes from distrusting Bishop because he’s an android to declaring Call trustworthy because she’s not human.)

Please mess with Ripley

The special edition differs from the theatrical version most dramatically in its beginning and its ending (though it also has a bit more Ripley character material). The special edition opens with a close-up on what is apparently a snarling xenomorph’s jaws; then the camera pulls back to show that it is actually an ordinary-sized housefly (or some similar insect) with some xenomorph features. So is this supposed to be an accidental byproduct of the experiments depicted in the movie? We’re never told. Pulling farther back, we see a human worker squishing the fly and then flicking it against a window, where it goes splat. At this point anyone who’s seen the previous movies expects the fly’s acidic blood to melt a hole in the window – with catastrophic results, since it quickly becomes clear that this window is on a spaceship. That would also be a nice foreshadowing of the hybrid’s fate later in the film. But no, nothing happens – it’s just a dead bug. And the next scene is the cloning lab that was the first scene of the theatrical version. So what was the point? After the atmospheric beginnings of the first three Alien movies, this pointless triviality is especially disappointing.

The ending scene, by contrast, is improved in the special edition. In the theatrical version, the Betty is landing on Earth, and Call looks out the window and declares with surprise that it’s beautiful (which is indeed a bit of a surprise, since Johner has told us earlier that Earth is a “shithole”), but we never see anything. In the special edition, by contrast, the Betty lands on a devastated nuclear landscape that was once Paris, and nobody declares anything beautiful – which seems more appropriate. (You can see the special-edition beginning and ending here and here; embedding disabled, alas.)

Next: Alien vs. Predator and Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem.

For Whom An Alien Heat Makes Festival, Part 1: ALIEN and ALIENS

Having fun on an outer space trip

with the Alien somewhere on the ship

I go to take a nap in bed

when I wake up something’s eating my head

Alien, you’re eating my leg

I fall on the floor and I’m dying

Alien, go back to your egg

I plead and I beg

go away, go away

– from a song I wrote in 1979 to the tune of

Simon & Garfunkel’s “Cecilia”

“It’s not as if anyone’s going to remember that critter once they’ve left the theater.”

– Robert Aldrich, in the interview that lost him the job as director of Alien

In preparation for Prometheus (which I saw the week before last), I’ve been watching, and/or rewatching, all the previous Alien films, as well as the Predator and Alien vs. Predator ones – not because I thought the latter would matter for the plot of Prometheus (after all, Ridley Scott has made clear that he doesn’t regard the AVP movies as canonical), but because they’re in some sense part of the same æsthetic universe (and boy, did that turn out to be right!). Up till now, although I’d had the dvds sitting around for a while, I’d seen only the first three Alien films (though not the special editions thereof) and the first two Predator films, so I had some catching up to do.

Now that I’ve seen all ten fairly recently, I thought I’d blog about them. These aren’t necessarily going to be full-fledged reviews, just some collections of thoughts.

Glancing around a few internet polls and review compilations, I gather that the movies (leaving out Prometheus) are widely ranked in roughly the following order, from most to least popular:

Aliens

Alien

Predator

Predators

Alien: Resurrection

Alien3

Predator 2

Alien vs. Predator

Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem

My own somewhat idiosyncratic (and certainly less well-ordered) ranking is a bit different:

Alien & Aliens (tied)

Alien3 & Prometheus (tied)

Predators

Alien: Resurrection

Alien vs. Predator

Predator 2

Predator

Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem

Probably the most controversial aspects of my ranking are the relatively high position of A3 and the relatively low position of the original Predator; more on these matters in later posts. (The Prometheus ranking is especially tentative, since I haven’t had as much time to reflect on it.)

The ten films separate naturally into pairs, so I’ll devote five posts to them, taking them in order of release date, starting with Alien and Aliens.

SPOILER WARNING:

Alien (1979):

In space, no one can hear you scream. Unless you’re screaming on a spaceship with oxygen and other people.

I hadn’t seen Alien in its entirety since it was in theatres, when it was the first R-rated movie I’d seen. I went in fairly fully informed, as I’d read the comic book, and possibly the novelisation too, as well as the making-of coverage in Starlog. At the time I was struck by a) the haunting creepiness of the visuals and soundtrack during the opening credits (none of the later films has measured up in that respect), and b) the sleek menacing amazingness of the xenomorph itself, which aesthetically obsessed me for a while as I drew it over and over. (For simplicity’s sake I’m going to follow the fan habit of calling the creatures in the Alien series “xenomorphs,” even though the term just means any kind of extraterrestial life form; I’ll reserve “alien” for the broader meaning, covering both xenomorphs and Predators.)

This time around I was struck both by the superb, unhurried pacing and by just how generally beautiful the film is – one of the three most beautiful in the series, the other two being Alien3 and Prometheus. (I realise that for many viewers, Alien3 is by contrast the ugliest film in the series. I’ll return to this point in Part 3.) One of the most beautiful scenes is the one where Brett is looking for the cat – but finding the xenomorph – in a room with chains hanging from the ceiling, and water dripping (a scene echoed in the later films, but never as successfully). I have no idea what the chains or the water are for – dripping water is not generally the best way to maintain metal chains in good preservation, I suspect – but the effect is haunting. (I’d embed the clip but it doesn’t look nearly as good on YouTube as it does on the dvd.)

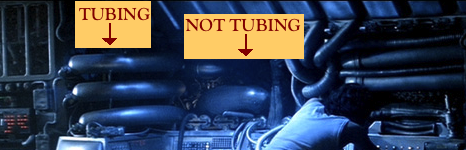

Another thing I noticed on this viewing is how, for the Earth tech in Alien, the film takes the basic spaceship look pioneered in their different ways by 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars, and tweaks it in an organic direction. Not anywhere near as organic as (what we may now call) the Engineers’ ship, of course, but subtly displaced in that direction; notice the quasi-organic bulges on the wall panels in the Nostromo. And notice also that the reason the xenomorph is able to hide in the shuttle at the end, initially unnoticed by Ripley, is that its head looks just like the tubing in the wall. (Imagine the xenomorph’s trying that in the bright white antiseptic interior of the Prometheus – though then again there seems to be no limit to what one can hide in the Prometheus.) Hence we can see continuity between the moderate organicism of the Nostromo and the extreme organicism of the Engineers’ ship; it’s as though the humans have already taken one step into the alien world from the start.

The plot with Ash also strikes me as borrowing from the HAL plot in 2001 – the A.I. with the hidden agenda and three-letter name who turns on the crew (even if David in Prometheus is more HAL-like in affect than Ash). And just as HAL is one letter backward from IBM (though the creators claim this is a coincidence), ASH is one letter backward from BTI, a prominent British computer company of the 1970s (though that may be a coincidence too). There’s even a very similar-looking scene in which Ripley, like Bowman, is trying to get through a door that Ash, like HAL, won’t open. Though alas, Ash doesn’t sing “Daisy” as he gets decapitated and incinerated. (The final shot of Ripley sleeping in her cryo-chamber also looks a bit like the final shot of Superbaby Bowman floating above earth.)

Don’t count on me, I Engineer

The film is not without flaws. In particular, there are some plot holes. How on earth, for example, can the Nostromo’s computer decode the Engineer’s signal? (Maybe Prometheus offers a possible answer to this question, but Prometheus wasn’t on the table at the time.) Also, in Marvel Comics there’s a famous puzzle about the Incredible Hulk: where does his extra mass come from when he transforms? In Alien, and indeed all the Alien movies, there’s a similar puzzle about the xenomorphs; how do they get so big, so fast? Given the live cocooning that they sometimes give their prey, we know that they don’t always eat what they catch; of course the cocooning isn’t shown in the first film (in the theatrical version, anyway) – but even before we knew about the cocooning, consider: between the time the tiny xenomorph bursts out of Kane’s chest and the time the now enormous xenomorph either kills or kidnaps Brett, no crew member has died; so it hasn’t gotten so large by eating the crew. Nor is there any mention of its having broken into ship’s stores to eat Weyland-Yutani’s version of MREs (which seem to consist largely of dodgy cornbread in any case). So where is it getting all those extra molecules? (This problem will assume particularly massive dimensions in Prometheus.)

Looking for Jonesy in all the wrong places

Moreover, the plot itself is not especially imaginative, since it’s essentially the standard hackneyed slasher-flick plot (lurking menace picks off the cast one by one, is thought defeated, until it suddenly and menacingly reemerges, before finally being finished off by the scantily-clad lone female survivor) – though admittedly this plot was not quite as hackneyed in 1979, when the Halloween franchise was only one movie old, while the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises were but gleams in their creators’ eyes and/or nostrils. (Alien has been accused of borrowing its main plot from a couple of episodes in A. E. van Vogt’s novel Voyage of the Space Beagle; see Wikipedia on the controversy. I wonder how successful Alien would have been if it had been titled Voyage of the Space Beagle. I realise it’s a reference to Darwin’s ship, but alas, that’s not the first image that “Space Beagle” brings to mind; I fear van Vogt must have had his mind in the null-A position when he chose that title. The working title of the film was Star Beast, which is better, but only just.)

Why is Ripley being mean to Bilbo?

On the other hand, the subplot with Ash and the Weyland-Yutani “crew expendable” directive adds another layer of complexity onto the basic plot – and sets a precedent: all the later movies add some degree of human perfidy, usually of the corporate and/or governmental variety, to the alien threat. (How much human perfidy Prometheus has depends on how much responsibility Weyland bears for David’s decisions.) But in the Alien movies, the villain is specifically the military-industrial complex, as Weyland-Yutani wants to use the xenomorph for its bioweapons division. (In the first film, the name is actually spelled “Weylan-Yutani,” but since the names were intended by the designer as references to Leyland and Toyota, and he actually refers to having gotten to “Weylan” from “Leyland” by “changing one letter,” I think it’s fair to treat “Weylan” as a typo for “Weyland,” as all the subsequent films have done.) Alien is also a rare case of a film set in outer space where the main characters are all working-class stiffs. (The name of the ship – as with Sulaco in the next film – is of course borrowed from Nostromo, Joseph Conrad’s novel of colonialism, exploitation, and corporate malfeasance.)

There is also, famously – and despite the final scene of Ripley being terrorised in her underwear – a feminist theme running through the film. On the one hand, the lead female character (a role originally scripted as male) is the most sensible and competent member of the crew, though her authority is constantly challenged and undermined by the others. On the other, the threat of rape and impregnation is no longer targeted specifically at women, but is expanded to include men – thus subverting a central trope of horror fiction.

The scene where Ripley refuses to let the infected Kane back on the ship is crucial to establishing her character. In a more traditional story it would be a male character taking the hardass position and a female character taking the sentimental but imprudent one – or if a woman did take the hardass position (even when it’s the obviously sensible position), she would thereby be identified by the script as an unsympathetic, overly “masculine” woman (as Vickers is in Prometheus). At this point in the story it’s not necessarily meant to be obvious to the viewer as yet that that’s not precisely what’s happening here too. Although in retrospect Ripley always seems central, by contrast with its successors Alien begins as an ensemble piece, with no one clear main character; the fact that she’s not with the team that explores the crashed ship may even serve to distract the audience’s attention from her importance. When the woman conventionally marked as unsympathetic and overly masculine emerges as the heroic protagonist – and not through being tamed and softened in the traditional narrative manner either – it’s a breath of fresh air, particularly in as traditionally male-oriented a genre as the big-budget science-fiction action film.

One of the great revelations of the film is of course Sigourney Weaver, in her first major movie role. (She’d been in Annie Hall, but playing a character listed only as “Alvy’s date outside theatre.” Remember her? Me neither.) Her performance is the steel spine running through the entire Alien series, and one of the many reasons (the others of course including scripts, direction, and design) that the Predator series has always been the weaker cousin, having never found as compelling a lead. (Hmm … Ripley/Ridley, what’s up with that?)

At one point the original script had called for the movie to end with the xenomorph’s biting Ripley’s head off and then making a radio transmission imitating her voice. I think we can all be grateful that option was dropped. (But it does foreshadow the voice-mimicking and higher intelligence of a different set of aliens in the Predator films, as well as of the T-1000 in Terminator 2.) Another early script had the xenomorph in the final scene become sexually attracted to Ripley, another idea well lost. (An early draft of Alien3 likewise had Ripley literally, sexually impregnated by the xenomorph. The bad ideas just won’t stop.)

The inclusion of Jonesy, the crew’s beloved cat, is also a nice touch, an invitation to shift perspective, since cats of course are ruthless and terrifying beasts of prey; the xenomorph is essentially a mouse’s-eye view of a cat.

My dvd set (the so-called Alien Quadrilogy, presumably on the theory that customers can’t grasp the word “tetralogy”) includes special editions of each film; in each case the special edition is an improvement. (I’ll use “special edition” as the generic term for director’s cuts, extended cuts, assembly cuts, unrated versions, et hoc genus omne.) In most cases the special edition is longer than the theatrical version, but not so in this case; yet it’s easier to identify what’s been added than what’s been removed, as the cuts mainly involved Ridley Scott’s shaving bits off here and there rather than deleting continuous chunks. One exception is the deletion of the scene where we learn that a) Ash was added at the last minute, at Weyland-Yutani’s insistence, to replace a different crew member, and b) Ripley doesn’t trust him. I can see why the scene was deleted, since (b) heightens audience suspicion of Ash too much, too soon; but it’s a pity that the information in (a) couldn’t have been incorporated at some point.

Of the restored scenes, one allows us actually to hear the Engineers’ eerie warning transmission; another has Ripley finding some of the missing crew members cocooned, and mercy-killing them (thus creating an inconsistency with Aliens, where Ripley says she’s never seen the cocooning before). (Some deleted scenes, included as dvd extras, are absent from both the theatrical and special editions.)

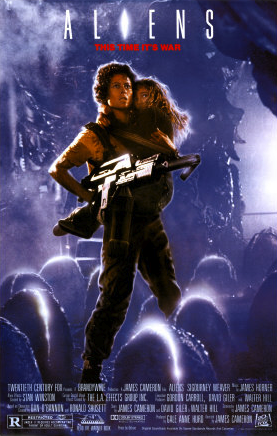

Aliens (1986):

Trivia fun: Aliens was not the first cinematic sequel to Alien; in between there was an unauthorised low-budget Italian followup, Alien 2: On Earth. (I haven’t seen it. I do not feel deprived.)

I have less to say about Aliens than I did about Alien. This is not to slight Aliens in any way; on the contrary, in many ways Aliens is an improvement over Alien. Admittedly the basic story situation isn’t especially innovative – it’s essentially what Doctor Who fans call a “base under siege” story (as A3 and Resurrection will be also). But Aliens complicates the base-under-siege plot in various ways; for one thing, it’s a base-under-siege story for only a relatively short, albeit narratively central, portion of the movie. The film breaks down into four parts: a) Ripley’s rescue and reawakening, and Weyland-Yutani’s dismissal of her story; b) Ripley’s return to LV-426 with the Marines, their initial encounter with the xenomorphs and rescue of Newt, and then being marooned on the planet; c) the “base under siege,” plus Burke’s sudden but inevitable betrayal; and finally d) Ripley’s return to the base to rescue Newt, followed by the duel with Xeno-Warrior-Queen on the shuttle.

Aliens expands Ripley’s role, explores her character in greater depth, gives her a more triumphant victory over the xenomorph (and over her own fear), and lets her engage in the kind of action-heroics usually reserved for male stars. The special edition also restores scenes revealing that Ripley’s daughter died of old age while Ripley was in cryogenic sleep – a fact that both heightens Ripley’s personal tragedy and explains her attachment to Newt. Weaver was understandably upset about the deletion of these character-rounding scenes, and it’s good to see them back. (In another restored scene, we see Newt’s family discovering the Engineers’ ship.)

Aliens also features a nice continuation of the political subtext about corporatism, with the government’s military apparently being put at the service of a private company; and James Cameron has noted that the soldiers’ initial swaggering overconfidence and subsequent panicked defeat was intended as a comment on the Vietnam war.

But from a feminist standpoint there’s a problematic aspect to Aliens as well, one not shared by the previous movie. As I noted a few months back whilst griping about the 2011 Doctor Who Christmas special:

The repeated message … that women’s strength comes from motherhood …. is one of the oldest arrows in patriarchy’s quiver. In a long literary tradition, a female character is most likely to be allowed to express strength and resolve if her doing so is somehow connected to her “natural” role as familial nurturer. Think of examples from Greek tragedy: Antigone and Electra, whose heroism is triggered by their feeling for a slain relative ….

The regrettable impression Aliens at least somewhat tends to create is that Ripley becomes an action hero, not because she is generally a courageous and resourceful person, but because the need to protect Newt has triggered her maternal instincts and flipped her into protective mama-bear mode; and the restored scenes about Ripley’s lost daughter, whatever their other virtues, only reinforce this impression – as does the implied parallel between Ripley and the xeno-queen, each fighting to protect her child(ren) from the other.

On the other hand, by granting Ripley the respect that no character evinced in Alien, Hicks and Bishop – not coincidentally the only two adult characters other than Ripley to survive the film’s events – somewhat redeem Aliens in this respect. (The subplot about Bishop’s overcoming Ripley’s anti-robot prejudice is another welcome complication to the story.)

At one point the marines’ dialogue suggests that humans have made contact (and even had sex) with intelligent extraterrestrials, specifically Arcturans, but this is never picked up on again, either in this film or in any subsequent one.

Aliens features a number of references designed for sf fans to pick up on: “drop ship” and “bug hunt” are nods to Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, the space station is named after Pohl’s Gateway, Bishop quotes Asimov’s laws of robotics, and Burke refers to a “Hyperdyne” robotics company reminiscent of Terminator’s Cyberdyne. And 57 years after the events of Alien, starship meal rations still feature an unappetising simulacrum of cornbread.

The movie also has a couple of plot problems, as this spoof points out:

Trivia fun: although they managed to make it look like dozens, the production crew for Aliens only had six xenomorphs to work with (just as Doctor Who’s first Dalek story had only four Daleks while trying to give the impression of a cityful).

Next: Predator and Predator 2.