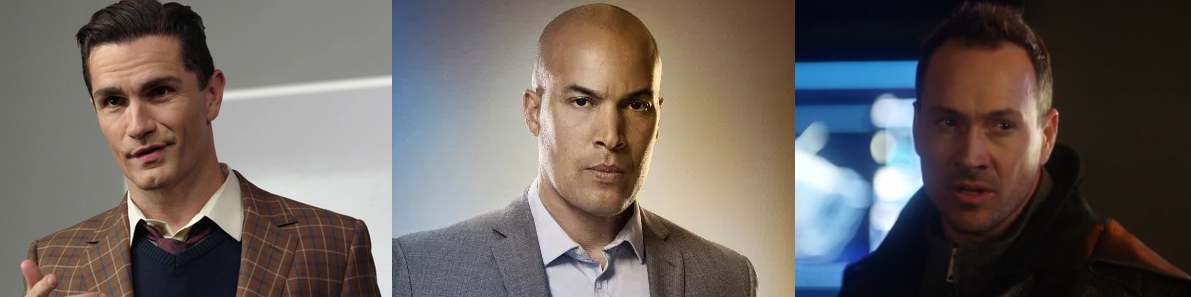

So Ben Lockwood (Agent Liberty) on Supergirl, Jace Turner on The Gifted, and Orlin Dwyer (Cicada) on The Flash are all different versions of the same character arc, right?

In all three cases, someone starts out a decent-seeming guy who initially has no problem with superhumans (be they aliens, mutants, or metahumans, depending on the show); but after his family suffers as a result of a conflict between two different groups of superhumans, he devotes himself to a campaign against them, drawing no distinction between the good and the bad, thereby becoming a partly sympathetic albeit mostly infuriating antagonist.

From left to right: Lockwood, Turner, Dwyer

There are some differences, of course. For example: Lockwood becomes the leader of the anti-superhuman campaign; Turner is just one member among many; and Dwyer works (mostly) solo. Also: Lockwood’s story is a clear – indeed heavy-handed – metaphor for anti-immigrant hysteria and alt-right media manipulation in the Age of Trump; Turner is a vaguer symbol for various kinds of bigotry and police overreach; and Dwyer’s character doesn’t seem to be intended to make any particular political point.

I’d also say that of the three, Lockwood is the most interesting – partly because Sam Witwer is the most talented of the three actors involved, partly because he gets more clever dialogue. Lockwood’s a less sympathetic antagonist than Turner because he’s slimier and more self-aware, while Turner is sort of perpetually befuddled; but Witwer gives Lockwood a kind of goofy, smarmy charm that’s creepily engaging, while Turner is as bland as a slab of beef. But the most boring and single-note of all is Dwyer, who seems to be of the school of thought that Christian Bale’s Batman voice was too soft and subtle. (Flash is lucky to have the best villain of the three shows this year, but it ain’t Dwyer.)

In related news: on tonight’s Supergirl, Lex Luthor refers to a quotation from Epicurus as being 230 years old. Off by a factor of ten, dude! If you’re that sloppy with measurement, no wonder your superhero-killing devices keep failing.

(I also have a hard time making sense of Manchester Black’s motivations in this episode. What was up with that? SPOILER ALERT: I’ll say more in the comments section below.)