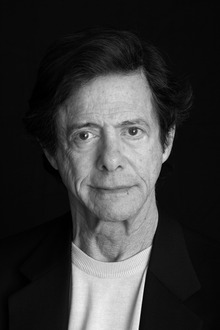

The first time I ever heard of Etheridge Knight’s poem “Hard Rock Returns to Prison from the Hospital for the Criminal Insane” was in a pearl-clutching 1983 screed by Leonard Peikoff titled “Assault from the Ivory Tower: The Professors’ War Against America.” (I believe I actually heard it first as a local Boston radio broadcast of a Ford Hall Forum talk. I was quite a bit more Randian in these days, but I knew enough to recognise many of his claims as bullshit; see addendum below.) Peikoff, high priest of the High Randian Church, writes:

If you want still more, turn to art – for instance, poetry – as it is taught today in our colleges. For an eloquent example, read the widely used Norton’s Introduction to Poetry, and see what modern poems are offered to students alongside the recognized classics of the past as equally deserving of study, analysis, respect. One typical entry, which immediately precedes a poem by Blake, is entitled “Hard Rock Returns to Prison from the Hospital for the Criminal Insane.” The poem begins: “Hard Rock was ‘known not to take no shit / From nobody’ …’ and continues in similar vein throughout. This item can be topped only by the volume’s editor, who discusses the poem reverently, explaining that it has a profound social message: “the despair of the hopeless.” Just as history is what historians say, so art today is supposed to be whatever the art world endorses, and this is the kind of stuff it is endorsing. After all, the modernists shrug, who is to say what’s really good in art? Aren’t Hard Rock’s feelings just as good as Tennyson’s or Milton’s?

Observe (as Randians like to say) that Peikoff feels no need to offer any argument or evidence that “Hard Rock Returns …” is a bad poem; he just leads with a sneer, expecting his herd of independent-minded followers to sneer obediently along with him.

Or are the quoted lines, along with the title, supposed to constitute the evidence all by themselves? Well then, what’s so self-evidently bad about the snippets Peikoff gives us? Is it that the quoted lines are ungrammatical? Then so much the worse for Mark Twain. Is it that Knight uses the word “shit”? Then so much the worse for Jonathan Swift. Is it that the lives of convicts and the mentally ill are inappropriate subjects for high art? Then so much the worse for Rand’s beloved Hugo and Dostoyevsky. Indeed so much the worse for Rand herself, who said that “for the purpose of dramatizing the conflict of independence versus conformity, a criminal – a social outcast – can be an eloquent symbol.”

In addition to getting the name of the anthology wrong (it’s the Norton Introduction, not Norton’s Introduction), Peikoff also misses the point of the poem; it’s not about “Hard Rock’s feelings” but rather the feelings of his fellow inmates. Perhaps Peikoff would have benefited from taking some of those classes he shudders at.

As for myself, I think it’s a damn good poem; and I guess I should thank Peikoff for introducing me to it. I also think it’s a poem concerning which anyone who claims to care about such things as heroic individualism and oppressive government ought to have been able to find something more intelligent to say than Peikoff managed. And it strikes me that the closing lines about “the doer of things / We dreamed of doing but could not bring ourselves to do” would not even be out of place in the pages of The Fountainhead or Ideal.

But judge for yourself.

Addendum: In the same essay, Peikoff also offers the following summary of Lawence Kohlberg’s theory of moral reasoning:

A social psychologist from Harvard, who also regards that code [= altruism and self-sacrifice] as self-evident, has devised a test to measure a person’s level of moral reasoning. … Here is a typical example. “Your spouse is dying from a rare cancer, and doctors believe a drug recently discovered by the town pharmacist may provide a cure. The pharmacist, however, charges $2,000 for the drug (which costs only $200 to make). You can’t afford the drug and can’t raise the money. …

Now comes the answer – six choices, and you must pick one; the answers are given in ascending order, the morally lowest first. The lowest is: not to steal the drug (not out of respect for property rights, that doesn’t enter even on the lowest rung of the test, but out of fear of jail). The other five answers all advocate stealing the drug; they differ merely in their reasons.

Thankfully, despite my youthful Randianism I knew enough in 1983 about theories of moral development to recognise that Peikoff is simply wrong; Kohlberg’s stages of development do not differ as to whether to steal the drug. Answers in favour of stealing and in favour of not stealing are found at every level; the levels differ only as to the kinds of reasons offered for stealing or for not stealing. (See, e.g., here.) That doesn’t mean there’s nothing to criticise about Kohlberg’s test; but Peikoff’s criticism is bogus, a sloppy failure to distinguish examples of answers from criteria for kinds of answer. He also takes Kohlberg’s test to be an evaluation of higher and lower levels as better and worse, whereas Kohlberg presents it value-neutrally, merely as a way of identifying earlier and later stages of psychological development.

Peikoff also expresses horror at a college course on “the different ways in which the handicapped individual and the idea of handicap have been regarded in Western Civilization,” with reference to such figues as “the fool, the madman, the blind beggar, and the witch.” What on earth, then, would Peikoff make of an author whose favourite play was about a man whose life is blighted by a fantastically large nose, and whose favourite novelist wrote books starring a hunchback and a man with a permanent grin carved onto his face?

Peikoff closes his essay by warning his readers/listeners that if they are of an individualist mindset and choose to pursue a university education, they will be in for a “miserable experience,” a “nightmare,” in which they will meet with “every kind of injustice, and even hatred,” will be “unbelievably bored most of the time,” and will generally be “alone and lonely.” The contrast between this gloomy prophecy and the joyous intellectual excitement that actually characterised my college years probably played a role in fueling my increasing skepticism of Randian dogma.