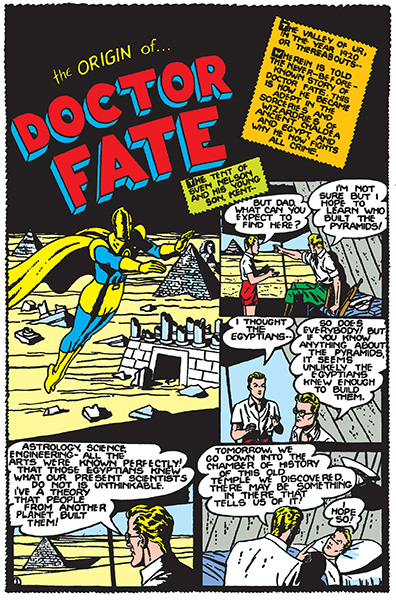

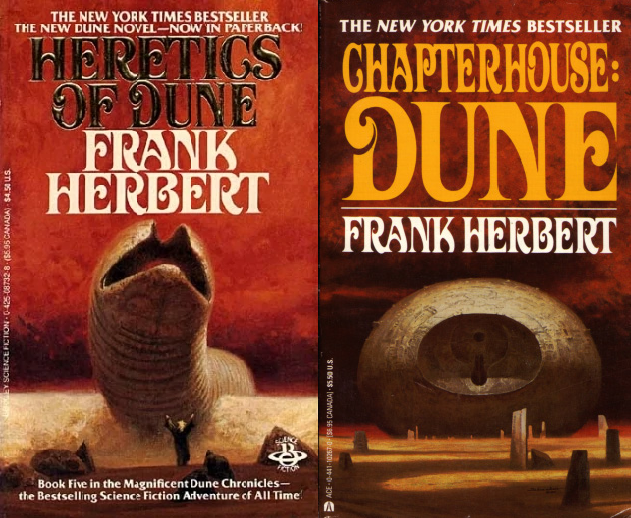

I’ve blogged before (see here, here, and here) about the influence of the Dune series on Star Wars. But I’ve recently reread the entire Dune series (the ones by Frank Herbert, I mean, not all of the posthumous continuations, though I’ve read a couple of those also), and having now refreshed my memory of the two final books that I’d remembered the least well, namely Heretics of Dune and Chapterhouse: Dune, I see still more influences of the Dune series, not just on Star Wars but also on Star Trek, and in particular on the most recent Trek series, Picard (for which SPOILERS follow). (Also, while I previously noted Jabba’s similarity to the God Emperor, I’d now say he’s really closest to being a cross between the God Emperor and Baron Harkonnen.)

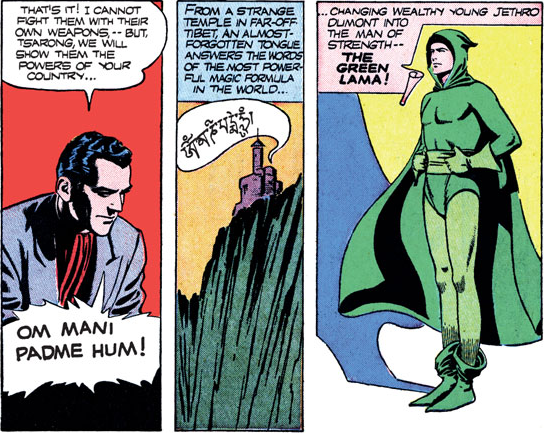

While the Bene Gesserit sisterhood is a major feature of all six original Dune novels, Heretics and Chapterhouse (henceforth HoD/ChD) focus on the Sisterhood both more closely and more sympathetically (though never uncritically) than do the earlier installments, and I suspect that the Bene Gesserit prohibition on personal emotional attachments, the pros and cons of which are central to the final two novels, was an influence on the similar Jedi prohibition in the Star Wars prequels. Yeah, I know, suspicion of attachment is a Buddhist thing (arguably the Buddhist thing), and Buddhism was always one of the influences on the concept of the Jedi; but it takes front and center in the prequel trilogy (which appeared after HoD/ChD) in a way it never did in the original trilogy (which appeared beforeHoD/ChD).

In HoD/ChD we see Darwi Odrade, who is the closest thing the final two books have to a central protagonist, making a convincing case that the Bene Gesserit rejection of love represents a crucial failing of the order; but on the other hand, there is also something to be said for the old guard’s case that Lady Jessica’s decision to defy the sisterhood out of love for Duke Leto has led to catastrophe – first to a massively destructive civil war under Paul Atreides, and then to a millennia-long dictatorship under the God Emperor. One can see this conflict mirrored in the prequel trilogy, where Anakin’s love for Padme and fear of losing her as he lost his mother is what leads him to fall to the dark side and aid in the rise of the Empire, thus arguably vindicating the prohibition on love – except that without the prohibition he might have felt freer to share his worries with his Jedi mentors rather than turning to Palpatine for advice. (And the Jedi could have freed Shmi from slavery and set her up in a nice apartment on Coruscant if they were worried that her son’s concern for her welfare would lead him into darkness.)

HoD/ChD also feature a conflict between the Bene Gesserit and their evil counterparts, the Honored Matres; and while the Matres don’t follow the Sith Rule of Two, they do ascend to leadership by assassinating their predecessor. They also practice a form of mind control, they scorn any form of compassion, and when they grow angry their eyes turn orange – all like the Sith.

(Promotion through assassination is of course also a Klingon thing – but one that was first established on Next Generation, which likewise came after HoD/ChD. Admittedly the idea of promotion through assassination is much older than any of these franchises, running back at least as far as

those trees in whose dim shadow

the ghastly priest doth reign,

the priest who slew the slayer

and shall himself be slain

but the parallels are still suggestive.)

The fact that ChD ends with the Bene Gesserit and Honored Matres being united under Murbella also prefigures one of two interpretations in Star Wars of what it means to bring balance to the Force – the interpretation, dominant in the tv series, where it is the light and the dark sides that need to be balanced, as opposed to the interpretation, dominant in the movies, that balance represents the triumph of light/balance over dark/imbalance. Moreover, members of the Bene Gesserit Sisterhood are often referred to as “witches” while of course the second Clone Wars tv series has its own sisterhood of mystical warriors, the “Nightsisters,” or “Witches of Dathomir.”

The Witches of Dathomir

As far as the recent sequel trilogy is concerned, while Palpatine’s reviving himself by transferring his consciousness into a cloned body is a callback to the 1990s Dark Empire arc in the comics, both were preceded by the use of the similar ghola concept in the Dune series. Also, Palpatine’s unsuccessful attempt to take over his granddaughter Rey’s body in Rise of Skywalker is prefigured in Baron Harkonnen’s largely successful attempt to take over his granddaughter Alia’s body in the second and third Dune books; and Rey’s being able to call on the powers of previous deceased Jedi echoes the Bene Gesserit’s use of “Other Memory.”

Turning to Star Trek: Picard: we’re introduced to two female-led Romulan societies, one sympathetic (the Qowat Milat) and one not (the Zhat Vash), in a way that parallels the (mostly) good and evil warrior sisterhoods in HoD/ChD (though the name “Qowat Milat” is most likely a nod to yet another warrior sisterhood, the Dora Milaje in Marvel’s Black Panther). (The Qowat Milat is explicitly said to be all-female, though they do give the male Elnor a Qowat Milat upbringing, as several of the male protagonsts in the Dune series receive a Bene Gesserit upbringing. (The Witches of Dathomir had male protegés too.) Nothing is explicitly said about the gender balance of the Zhat Vash, but while they do have at least one male operative, all the initiates we see attending the Admonition are female, as far as I could tell.) The sensual, manipulative, ruthlessly violent, psychopathically unempathetic Narissa, the Zhat Vash operative we get to know best, also acts very much like one of Herbert’s Honored Matres.

The Qowat Milat, by contrast, live by a rule of “absolute candor” – which is not (to put it mildly) a trait we would have associated with the Bene Gesserit after reading only the first four Dune books; but in HoD/ChD, the term “candor” is repeatedly and explicitly associated with the Bene Gesserit outlook (though the Bene Gesserit seem to have a somewhat more flexible understanding of this trait than do the Qowat Milat).

The Bene Gesserit

The Qowat Milat

The Zhat Vash

Continuing the parallels, the Romulan hostility toward artificial intelligence parallels the Butlerian Jihad in the Dune series. The Admonition, in Star Trek: Picard, contains coded memories that Zhat Vash initiates access through a ritual that risks driving them insane, rather like the Spice Agony via which Bene Gesserit initiates access their ancestral memories, risking death or possession.

The revelation that the Zhat Vash in Picard are motivated by fear of invasion from a distant machine civilisation bent on destroying humanity seems to echo the fact that in HoD/ChD their counterpart, the Honored Matres, are fleeing from a mysterious Enemy beyond known space, which in the continuations by Brian Herbert and Kevin Anderson turns out to be a distant machine civilisation bent on destroying humanity (even though ChD suggests pretty strongly that Frank Herbert was planning to go in a different direction regarding the Enemy’s identity).

Moreover, in Picard we learn that one can survive death by transferring one’s consciousness into an artificial body, a clone of oneself, called a golem – which is not how a golem works in Jewish folklore (the traditional golem had its own body and consciousness, both artificial and somewhat rough-hewn, but neither one a copy of any actual pre-existing person), but is rather more how a ghola works in the Dune novels.

From the 1915 film The Golem

And Picard even says “Fear is the great destroyer,” which sounds a lot like the Bene Gesserit’s Litany Against Fear: “Fear is the mind-killer; fear is the little death that brings total obliteration.”

There are other parallels between Dune and Star Trek where it’s unclear whether there was influence or, if so, in what direction. In the first four Dune novels, we know that Bene Gesserit initiates who’ve been through the Spice Agony have access to all the memories of their female ancestors. (Aside: as a kwisatz haderach, Paul is supposed to be unique in having access to the memories of his male ancestors as well, though he never makes much use of them; but Alia obviously has access to the memories of her male ancestors too, since otherwise she wouldn’t be at risk of possession by the Baron. Does this mean that a female kwisatz haderach is possible after all? It’s odd that this is never addressed.) But in HoD/ChD, we learn that the Bene Gesserit have another route of access to “Other Memory”; at the moment of death, one Bene Gesserit can telepathically transfer her fund of memories, both from her own life and from her stored lives, to another Bene Gesserit by touching foreheads, thus granting the recipient access to non-ancestral memories as well.

This is obviously similar to how katra transfer works in The Search for Spock, which was released in June 1984 – though it’s arguably hinted at in 1982’s Wrath of Khan. HoD was released in April 1984 – too close, I think, for it to have either influenced or been influenced by Search for Spock. I can’t recall this ability being introduced prior to HoD/ChD – though it may be intended to fill a plot hole where, in God Emperor (IIRC, and I’m not sure I do), it’s implied that a Bene Gesserit initiate remembers the deaths of her predecessors, which she could hardly do if memories were transferred only at the moment of conception. Hmm, unclear.

I also see some (very broad) parallels between the first Dune novel and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Both start with the protagonist, a brilliant but moody young prince, losing his father to treachery; both end with a public duel in which the prince’s opponent cheats by using a poisoned blade – and where the villainous antagonist who has arranged the duel, and is now seated among the spectators, ends up getting killed as well. Both involve intrigue in sprawling castles with ample opportunities for eavesdropping, secret messages, and assassination. In both cases, the protagonist must hide (Dune) or dissimulate (Hamlet) until he is in a position to avenge his father’s death. Both Paul and Hamlet spend a lot of time brooding angstily over the roles in which destiny has cast them, though both act with great shrewdness and dispatch when the time comes. Both make crucial use of their fathers’ signet rings. And even the opening of David Lynch’s Dune, opening with the Atreides stronghold on a cliff above the violent surf of Caladan –

– reminds me of the similar opening of Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet:

– or likewise that of Kozintsev:

Of course one obvious difference is that most of the action in Dune takes place far away from castles, out in the wilds of the desert, whereas the action of Hamlet all seems to take place within the claustrophobic hallways of Elsinore. But in fact Hamlet does see a fair bit of action away from Elsinore, though it all takes place offstage – his sea voyage to England, his switching the letters so as to send Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern to their deaths, and his fight with, capture by, and subsequent befriending of the pirates (not entirely unlike Paul’s adventure with the Fremen).*

And I can’t resist adding that Shakespeare gives Hamlet the line “Your worm is your only emperor.”