Who said this?

It is so easy to say “we” and bow our heads together.

I must say “I” alone and bow my head alone

for it is I alone who is living my life.

I have beloved companions

but they do not eat nor sleep for me

and even they must say “I.”

Who said this?

It is so easy to say “we” and bow our heads together.

I must say “I” alone and bow my head alone

for it is I alone who is living my life.

I have beloved companions

but they do not eat nor sleep for me

and even they must say “I.”

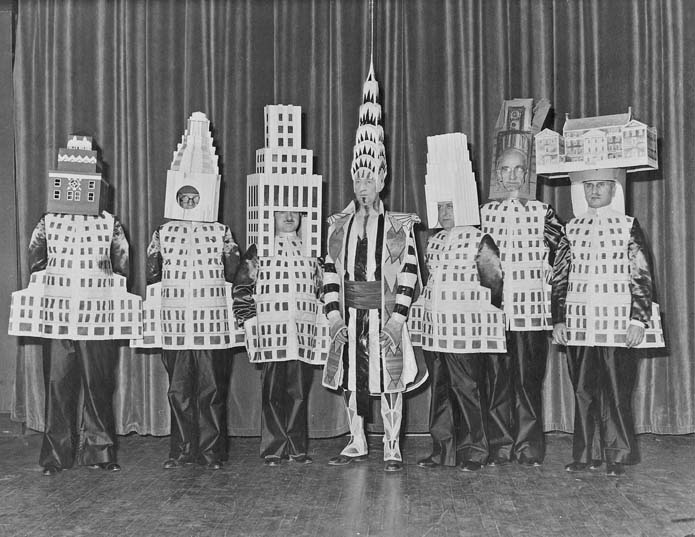

In The Fountainhead, Rand offers a satirical description of an architectural costume party:

That winter the annual costume Arts Ball was an event of greater brilliance and originality than usual. Athelstan Beasely, the leading spirit of its organization, had had what he called a stroke of genius: all the architects were invited to come dressed as their best buildings. It was a huge success.

Peter Keating was the star of the evening. He looked wonderful as the Cosmo-Slotnick Building. An exact papier-mâché replica of his famous structure covered him from head to knees; one could not see his face, but his bright eyes peered from behind the windows of the top floor, and the crowning pyramid of the roof rose over his head; the colonnade hit him somewhere about the diaphragm, and he wagged a finger through the portals of the great entrance door. His legs were free to move with his usual elegance, in faultless dress trousers and patent-leather pumps.

Guy Francon was very impressive as the Frink National Bank Building, although the structure looked a little squatter than in the original, in order to allow for Francon’s stomach; the Hadrian torch over his head had a real electric bulb lit by a miniature battery. Ralston Holcombe was magnificent as a state capitol, and Gordon L. Prescott was very masculine as a grain elevator. Eugene Pettingill waddled about on his skinny, ancient legs, small and bent, an imposing Park Avenue hotel, with horn-rimmed spectacles peering from under the majestic tower. Two wits engaged in a duel, butting each other in the belly with famous spires, great landmarks of the city that greet the ships approaching from across the ocean. Everybody had lots of fun.

Many of the architects, Athelstan Beasely in particular, commented resentfully on Howard Roark who had been invited and did not come. They had expected to see him dressed as the Enright House. (Fountainhead, II.11)

Rand’s account was based on an actual historical incident that she recorded in her journals while working on the novel:

The Beaux-Arts Ball (January 23, 1931) where famous architects wore costumes representing one of their buildings. “Human Skyline for Beaux-Arts Ball.” … Note the little guy with the glasses peering through a hole in his headpiece – the Waldorf-Astoria. (Journals of Ayn Rand, p. 160)

Here, presumably, is the photo Rand saw:

(CHT Jesse Walker.)

I’ve gotta say, the Chrysler Building guy is cheating. Hat aside, his costume looks less like a building than like some sort of actual and rather snazzy clothing.

Many of the characters in The Fountainhead are based, sort of, on real-life models. I say “sort of” because it is generally not the personality or biography but the work and social role that is grounded in a real-life model. For example, Howard Roark and Gail Wynand do not resemble Frank Lloyd Wright and William Randolph Hearst, respectively, in their personal character or the details of their career (Hearst, for example, was the son of a wealthy industrialist, while Wynand grew up on the streets of Hell’s Kitchen; and Wynand’s personality owes more to Sienkiewicz’s Petronius, with a sprinkling of Nietzsche); but Roark is the same kind of architect as Wright, and Wynand the same kind of newspaper magnate as Hearst.

The pattern continues with the book’s other characters. Austen Heller, the “star columnist” and “literary critic” with “better manners than the social elite whom he usually mocked” and “a tougher constitution than the laborers whom he usually defended,” and who devotes himself to “the destruction of all forms of compulsion, private or public,” is an obvious nod to Rand’s idol H. L. Mencken, though personally Heller is an Oxford-educated Englishman. Lois Cook’s writing style is a parody of Gertrude Stein, but Cook herself is not especially so. Rand based Ellsworth Toohey’s personality on Harold Laski, but in his work as an architectural critic Toohey is clearly modeled on Lewis Mumford, and his book Sermons in Stone on Mumford’s Sticks and Stones. Ralston Holcombe is based in his architectural project on Thomas Hastings, but Hastings did not, for example, have Holcombe’s “rich white hair … to his shoulders in the sweep of a medieval mane.”

Dominique Francon’s personality is famously based on Rand herself “in a bad mood,” but in her work as an architectural critic Dominique instead mirrors the literary criticism of Rand’s mentor Isabel Paterson. Consider this passage from one of Dominique’s columns:

You enter a magnificent lobby of golden marble and you think that this is the City Hall or the Main Post Office, but it isn’t. It has, however, everything: the mezzanine with the colonnade and the stairway with a goitre and the cartouches in the form of looped leather belts. Only it’s not leather, it’s marble. The dining room has a splendid bronze gate, placed by mistake on the ceiling, in the shape of a trellis entwined with fresh bronze grapes. There are dead ducks and rabbits hanging on the wall panels, in bouquets of carrots, petunias and string beans. I do not think these would have been very attractive if real, but since they are bad plaster imitations, it is all right. …The bedroom windows face a brick wall, not a very neat wall, but nobody needs to see the bedrooms. …The front windows are large enough and admit plenty of light, as well as the feet of the marble cupids that roost on the outside. The cupids are well fed and present a pretty picture to the street, against the severe granite of the façade; they are quite commendable, unless you just can’t stand to look at dimpled soles every time you glance out to see whether it’s raining. If you get tired of it, you can always look out of the central windows of the third floor, and into the cast-iron rump of Mercury who sits on top of the pediment over the entrance. It’s a very beautiful entrance. Tomorrow, we shall visit the home of Mr. and Mrs. Smythe-Pickering. (Fountainhead I.3.)

This arch, ironic tone is not Rand’s customary style of criticism; but it is vintage Paterson.

The character of Roark’s mentor Henry Cameron is closely based on Wright’s mentor Louis Sullivan in his career and architectural ideas, but not especially in his personality. The recent revelation that Rand was a fan of Arthur Conan Doyle’s novel The Lost World has previously led me to speculate that Professor Challenger might have been the model for the personal aspect of Cameron. Here’s a pair of passages to illustrate my hypothesis:

|

There was a tap at a door, a bull’s bellow from within, and I was face to face with the Professor.

He sat in a rotating chair behind a broad table …. It was his size which took one’s breath away – his size and his imposing presence. … He had the face and beard which I associate with an Assyrian bull; the former florid, the latter so black as almost to have a suspicion of blue, spade-shaped and rippling down over his chest. The hair was peculiar, plastered down in front in a long, curving wisp over his massive forehead. The eyes were blue-gray under great black tufts, very clear, very critical, and very masterful. A huge spread of shoulders and a chest like a barrel were the other parts of him which appeared above the table, save for two enormous hands covered with long black hair. This and a bellowing, roaring, rumbling voice made up my first impression of the notorious Professor Challenger. “Well?” said he, with a most insolent stare. “What now?” … “You were good enough to give me an appointment, sir,” said I, humbly, producing his envelope. … “Oh, you are the young person who cannot understand plain English, are you? … Well, at least you are better than that herd of swine in Vienna, whose gregarious grunt is, however, not more offensive than the isolated effort of the British hog.” He glared at me as the present representative of the beast. … “… Well, sir, let us do what we can to curtail this visit, which can hardly be agreeable to you, and is inexpressibly irksome to me. …” … “It proves,” he roared, with a sudden blast of fury, “that you are the damnedest imposter in London – a vile, crawling journalist, who has no more science than he has decency in his composition!” He had sprung to his feet with a mad rage in his eyes. … He was slowly advancing in a peculiarly menacing way …. “I have thrown several of you out of the house. You will be the fourth or fifth. Three pound fifteen each – that is how it averaged. Expensive, but very necessary. Now, sir, why should you not follow your brethren? I rather think you must.” He resumed his unpleasant and stealthy advance, pointing his toes as he walked, like a dancing master. (Conan Doyle, ch. 3) |

“Mr. Cameron, there’s a fellow outside says he’s looking for a job here.”

Then a voice answered, a strong, clear voice that held no tones of age: “Why, the damn fool! Throw him out … Wait! Send him in!” … Henry Cameron sat at his desk at the end of a long, bare room. He sat bent forward, his forearms on the desk, his two hands closed before him. His hair and his beard were coal black, with coarse threads of white. The muscles of his short, thick neck bulged like ropes. He wore a white shirt with the sleeves rolled above the elbows; the bare arms were hard, heavy and brown. The flesh of his broad face was rigid, as if it had aged by compression. The eyes were dark, young, living. … “What do you want?” snapped Cameron. “I should like to work for you,” said Roark quietly. … “What infernal impudence made you presume that I’d want you? Have you decided that I’m so hard up that I’d throw the gates open for any punk who’d do me the honor? … Great!” Cameron slapped the desk with his fist and laughed. “Splendid! You’re not good enough for the lice nest at Stanton, but you’ll work for Henry Cameron! …” Cameron stared at him, his thick fingers drumming against the pile of drawings. … “God damn you!” roared Cameron suddenly, leaning forward. “I didn’t ask you to come here! I don’t need any draftsmen! … I’m perfectly happy with the drooling dolts I’ve got here, who never had anything and never will have and it makes no difference what becomes of them. That’s all I want. … I don’t want to see you. I don’t like you. I don’t like your face. You look like an insufferable egotist. You’re impertinent. You’re too sure of yourself. Twenty years ago I’d have punched your face with the greatest of pleasure. You’re coming to work here tomorrow at nine o’clock sharp.” … “Yes,” said Roark, rising. … Roark extended his hand for the drawings. “Leave these here!” bellowed Cameron. “Now get out!” (Rand, I.3) |

Unlike my previous example, these parallels are not so close as to rule out the possibility of coincidence, but they are at least suggestive.

That Ayn Rand was a fan of Louis Sullivan is no secret; the character of Henry Cameron in The Fountainhead is obviously based on him, and she speaks favourably of his Autobiography of an Idea in her introduction to We the Living.

That Ayn Rand was a fan of Louis Sullivan is no secret; the character of Henry Cameron in The Fountainhead is obviously based on him, and she speaks favourably of his Autobiography of an Idea in her introduction to We the Living.

What’s less seldom recognised is just how closely Rand was indebted to Sullivan’s autobiography – as well as to Claude Bragdon’s introduction to that work. In what follows, then, I’ve paired Rand’s descriptions of Cameron’s ideas and career in The Fountainhead with the corresponding passages from Sullivan and Bragdon:

| Bragdon:

He held the conviction that no architectural dictum, or tradition, or superstition, or habit, should stand in the way of realizing an honest architecture, based on well-defined needs and useful purposes: the function determining the form, the form expressing the function. … |

Rand:

He said only that the form of a building must follow its function; that the structure of a building is the key to its beauty; that new methods of construction demand new forms …. |

| Louis Sullivan has the distinction of having been, perhaps, the first squarely to face the expressional problem of the steel-framed skyscraper and to deal with it honestly and logically. … To him the tallness of the skyscraper was not an embarrassment, but an inspiration – the force of altitude must be in it; it must be a proud and soaring thing, without a dissenting line from bottom to top. Accordingly, flushed with a fine creative frenzy, he flung upward his tiers and disposed his windows as necessity, not tradition, demanded, making the masonry appear what it had in fact become – a shell, a casing merely, the steel skeleton being sensed, so to speak, like bones beneath their layer of flesh. Then, over it all, he wove a web of beautiful ornament – flowers and frost, delicate as lace and strong as steel. … |

The explosion came with the birth of the skyscraper. …. Henry Cameron was among the first to understand this new miracle and to give it form. He was among the first and the few who accepted the truth that a tall building must look tall. While architects cursed, wondering how to make a twenty-story building look like an old brick mansion, while they used every horizontal device available in order to cheat it of its height, shrink it down to tradition, hide the shame of its steel, make it small, safe and ancient – Henry Cameron designed skyscrapers in straight, vertical lines, flaunting their steel and height. … |

| Sullivan:

It was deemed fitting by all the people that the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America by one Christopher Columbus, should be celebrated by a great World Exposition …. Chicago was ripe and ready for such an undertaking. … It was to be called The White City by the Lake. … The landscape work, in its genial distribution of lagoons, wooded islands, lawns, shrubbery and plantings, did much to soften an otherwise mechanical display …. |

Rand:

The Columbian Exposition of Chicago opened in the year 1893. The Rome of two thousand years ago rose on the shores of Lake Michigan, a Rome improved by pieces of France, Spain, Athens and every style that followed it. It was a “Dream City” of columns, triumphal arches, blue lagoons, crystal fountains and popcorn. Its architects competed on who could steal best, from the oldest source and from the most sources at once. It spread before the eyes of a new country every structural crime ever committed in all the old ones. … |

| The work completed, the gates thrown open 1 May, 1893, the crowds flowed in from every quarter …. These crowds were astonished. … They went away, spreading again over the land, returning to their homes, each one of them carrying in the soul the shadow of the white cloud, each of them permeated by the most subtle and slow-acting of poisons …. Thus they departed joyously, carriers of contagion …. There came a violent outbreak of the Classic and the Renaissance in the East, which slowly spread westward, contaminating all that it touched, both at its source and outward …. through a process of vaccination with the lymph of every known European style, period and accident …. We have Tudor for colleges and residences; Roman for banks, and railway stations and libraries, or Greek if you like – some customers prefer the Ionic to the Doric. … |

It was white as a plague, and it spread as such.

People came, looked, were astounded, and carried away with them, to the cities of America, the seeds of what they had seen. The seeds sprouted into weeds; into shingled post offices with Doric porticos, brick mansions with iron pediments, lofts made of twelve Parthenons piled on top of one another. The weeds grew and choked everything else. … |

Nor is Sullivan’s influence confined to The Fountainhead. His remark later in the autobiography that the natural man “reverses the dictum ‘I think: Therefore I am.’ It becomes in him, I am: Therefore I inquire and do! It is this affirmative ‘I AM’ that is man’s reality” anticipates both Prometheus’s discovery in Anthem – “I am. I think. I will. … What must I say besides?” and John Galt’s advice in Atlas Shrugged, “reversing a costly historical error, to declare: I am, therefore I’ll think.”

All the roles for the third installment of Atlas Shrugged have been recast once again. I continue to be filled with a lack of anticipation.

At the time I wrote about the transubstantiation model of the state I had forgotten Orwell’s very similar description of doublethink:

The power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them …. To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, to hold simultaneously two opinions which cancelled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it … to forget, whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again, and above all, to apply the same process to the process itself – that was the ultimate subtlety; consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed. … To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, and then, when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just as long as it is needed, to deny the existence of objective reality and all the while to take account of the reality which one denies – all this is indispensably necessary. … The process has to be conscious, or it would not be carried out with sufficient precision, but it also has to be unconscious, or it would bring with it a feeling of falsity and hence of guilt ….

I probably did remember the following passage from Rand:

He was doling his sentences out with cautious slowness, balancing himself between word and intonation to hit the right degree of semi clarity. He wanted her to understand, but he did not want her to understand fully, explicitly, down to the root – since the essence of that modern language, which he had learned to speak expertly, was never to let oneself or others understand anything down to the root.

Whether Rand’s description of “that modern language” was influenced by Orwell’s account of Newspeak I don’t know, just as I don’t know whether Orwell’s Newspeak was influenced in turn by the similar device in Rand’s Anthem.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |