As those who follow me on facebook will know, I recently got back from a trip to Greece. (My third; see my notes on the first and second – in each case for the annual AtInER philosophy conference).

I’m reproducing here the most salient excerpts from my facebook posts. But if you want to see the full story, including more commentary, banter with my facebook friends, and lots and lots of photos of Hydra, check out my facebook page for the past couple of weeks. Other photos, taken with my regular camera, will be posted in due course.

My voyage to Greece:

I’m on an airplane in flight, posting to facebook via my new smartphone. I have finally entered the 21st century.

So, this morning I flew from one city with a Greek name to another city with a Greek name. Now I’m crossing an ocean with a Greek name, on my way to yet another city with a Greek name. Any guesses?

My free weekend before the conference:

Last night my waiter tried to dissuade me from ordering a second iced coffee, on the grounds that it would keep me awake. “Too strong!” he said, miming a strongman’s pose.

But caffeine is a drug that has surprisingly little effect on my system. (Morphine is another, as I sadly learned 21 years ago when I was hospitalised with 4 broken ribs after a car crash.)

I was also warned at my hotel that the room I had chosen had too much street noise and would keep me awake. Everyone seems to be concerned with my sleep cycle! But street noise is another thing that never keeps me awake, city boy that I am. …

Right now I’m having lamb pilaf and ginger lemonade in the Acropolis Museum. …

The menu did say this was a Cretan dish. But that was probably a lie. …

All Cretans play the lyre. …

The view from the Acropolis Museum restaurant is kinda purty. It’s a big hill with some old building on it. …

Spent the morning hiking up to the Pnyx, site of the old Athenian Assembly. Now I’m in a sidewalk cafe across from the ruins of the Sanctuary of Zeus in the street leading down from the Pnyx, sipping lemon mint iced tea.

Robert Louis Stevenson said it was better to travel hopefully than to arrive. (This was even inscribed on the entrance to my freshman dorm.) When I contrast my process of getting here (TSA hassles, plus being crammed in an airline seat for eleven hours) with being here, I find it hard to agree with him.

Side note: I notice on the menu that the Greek for “appetizers” is “orektika” – from “orexis,” Aristotle’s word for desire or appetite. Constant such linguistic reminders of antiquity everywhere here.

It was hot on the hike up, but I’m under an awning here and there’s a cool breeze. A band of musicians just came by. Also a group of cyclists on wooden bicycles. …

Now I’m having lunch at To Steki Tou Elia, a place famous for its lambchops. I accidentally shared some with a cat.

I’ve now stood on the spot where Pericles, Demosthenes, and Alcibiades addressed the populace. But it didn’t make me hungry for power. It did, however, make me thirsty for lemon mint iced tea.

The speaker would have had a nice view of the Gulf, assuming there weren’t trees or buildings in the way back then. …

Another ancient callback: on the metro the word for “gap” in “mind the gap” is the same as Democritus’s word for the Void. … Mind the Void!

Continuing the Democritean theme, “atomic cigarettes” are prohibited on the metro. …

Tonight I’m sampling more purportedly Cretan cuisine – this time, a cocktail combining raki, grapefruit, and blackberry. I’m turning into a real Minoarchist.

Tomorrow morning the actual conference begins.

The conference was held in the Titania Hotel, a short walk from my hostel. My first time here the conference was rather disorganised, but it has greatly improved both in organisation and in quality of presentations. My talk was on a left-libertarian analysis of labour exploitation, originally planned for a volume project that fell through but may possibly be revived. Got some useful feedback.

This conference hotel has meeting rooms named after Socrates, Plato, Homer, and Solon. No Aristotle! I am offended.

I’m going to protest by engaging in a sit-in. I’m going to sit down right here and listen to this lecture. …

This is a truly international conference, with speakers from Poland, Chile, Taiwan, New Zealand, India, Germany, South Africa, Israel, Spain, Sweden, Mexico, Switzerland, etc.

Whenever I mention that I teach in Alabama, people react as though I’d said I was from a Taliban enclave. We’re famous!

Conference highlights, irony edition: a debate between a white German male who was attacking Kant for having racist, sexist, and colonialist views, and a Chilean woman of indigenous background who was defending Kant on those points. (I agreed with most of what both of them said, actually.)

Then the first conference tour:

Today, a tour as part of the conference: we’re headed to Poros, Mycenae, and the Corinthian Canal. I’ve seen Poros before but not the other two.

Mycenean civilisation, also known as the Mycelial Network, was of course the inspiration for Homer Simpson when he composed the Idiocy and the Oddity. Mycenae is particularly famous for its Lyin’ Gate, the greatest ancient monument to mendacity outside of Crete.

As Ludwig van Beethovstein wrote in his Philosophical Convolutions (at least according to Epimenides’ recension): “If a Mycenean could lie, we would not understand him. A mouth can lie only in a Cretan face.” …

So far this tour guide is highly accurate – way better than my Delphi guide on my previous visit to Greece.

The drive from Athens to Mycenae is really beautiful, as is the view from the fortress. The canal and the fortress (monumental structures from very different centuries) are duly impressive (sublime).

Hard to believe, but before Schliemann, archaeologists weren’t much interested in Mycenae; they were focused on the Classical era.

Lovecraft is always referring to monumental structures as “cyclopean”; this derives from early Greek assumptions that Mycenae ruins must have been built by Cyclopes (because they were giants, not because they were one-eyed), since the stones seemed too massive to have been piled up by human beings.

The modern equivalent is the assumption that the pyramids etc. must have been built by aliens.

The Anglo-Saxons had the same view of monumental structures (such as Stonehenge) in Britain, calling them “orthanc enta geweorc,” “the cunning work of giants” – which Tolkien reinterpreted as “Orthanc, the fortress (taken by) the Ents.”

I remember seeing a special in which people of Aztec, Inca, or Mayan ancestry (I forget which) described how they’d wept when they realised that their own ancestors had built the monumental buildings there.

Similarly, the European rulers of Zimbabwe always insisted that the fortresses there had been built by a lost white race because they were too impressive to have been built by black natives; it was a liberating moment when the Zimbabweans realised the Europeans were mistaken.

Just came back from our second Mycenean site, the “Treasury of Atreus” (actually a tomb), which was also pretty damn impressive.

Mycenae really was like something out of fantasy or science fiction.

Then from Mycenae to Epidauros, then a crazy beautiful drive along the coast to Galatas, then a ferry to Poros, now lunch on the waterfront.

Just today I’ve passed within sight of so many places that are legends to me: Acrocorinth, Argos, Parnassos, Arcadia … Eleusis, Megara ….

Our tour guide said that the length of Greece’s coastline is the same as the length of Africa’s coastline.

Well, yes and no. It depends on the degree of resolution.

Our tour guide says that the Greek govt is deliberately destroying the independent fishing industry. When fishermen retire they sell their fishing licenses back to the govt (at a loss) and the govt isn’t issuing new ones. So there’s no way for a 20yo to become a fisherman. When you turn your license in, the govt also sends a bulldozer to demolish your boat.

The official reason for this is environmental protection. But, says our guide, not all fishing practices are harmful to the environment; the real reason, on her view, is that the govt is promoting and subsidising large corporate industrial fish farming.

Wish I were shocked. …

In the Meno, Plato inquires whether true belief about how to get from Athens to Larissa is as valuable as knowledge of how to get from Athens to Larissa.

In the Physics, Aristotle inquires whether the road from Athens to Larissa is the same as the road from Larissa to Athens.

Those are both texts I’ve been familiar with for around 35 years.

On the highway leading out of Athens on the bus trip yesterday, I saw signs for Larissa. It was a surreal feeling, as though I’d stepped into a philosophical example.

Rather than revisit Delphi, I took a free day in Athens, where I first revisited the Agora:

Sitting on a shaded bench in the Agora, absorbed in my thoughts, only half-listening to a nearby tour guide talking about Plato, Aristotle, etc.

Suddenly I think: “wow, it’s amazing how much of what she’s saying I can understand, given that it’s in (modern) Greek.”

Then I think: “wait, there’s no way I should be able to understand her this well.”

Then I realise she’s actually speaking in French.

Touristic informations: in the Athenian Agora, you do NOT need to climb the steep path with many steps to reach the Hephaestion. Approach it from the left instead of from the front, and there is a gently sloping path with NO STEPS that takes you there. … Particularly useful to know because the steps are a bit slippery and there’s no handrail.

You’re welcome. (imagine sung by Maui)

Further info: the cave exhibited as “Socrates’ Prison” on Philopappou Hill is no such thing. The likely actual site is in the Agora itself, near the extreme southwest corner (in the same vicinity as the beginning of the easy path to the Hephaestion).

Then the Byzantine Museum, which I hadn’t been to before:

St. Christopher Cynocephalus was a Good Boy. Yes he was.

Saw this icon in the Byzantine Museum (which incidentally seems to be bigger on the inside; it looks fairly small when you first enter, but every time you think you’ve seen all the rooms, there’s another, and another).

The story with dogheaded St. Chris, apparently, is that some scribe misread a phrase meaning “Canaanite” as “caninite.” Oops. I mean, woof. So I guess it’s not Anubis sneaking into the Christian tent.

In other news, more Democritean signage: a notice in an elevator says in English “no more than four people,” but the Greek, instead of “people,” says “atoma” (atoms = indivisibles = individuals).

Then the Lyceum, which I’d only sort of been to before:

The signage at Aristotle’s Lyceum repeats the late Roman myth that his school was called “Peripatetic” because he lectured while walking around.

No, it’s because his school was located in a peripatos, a covered walkway (just as the Stoics were so named because they met in the Stoa Poikilē [Painted Colonnade]).

Indeed, Aristotle’s texts strongly suggest that he lectured from notes while pointing to diagrams and other classroom fixtures. Difficult to do so while wandering about.

At least the Lyceum signage cites the rather late Aulus Gellius as a source for the walking-about theory rather than just asserting it as known.

Everyone knows that Aulus Gellius spent his nights in his attic, so what does he know anyway?

On my previous visit to Athens (2013) I blogged:

“On my last night, right behind my hotel I found, and had dinner in, a delightful neighborhood called Psirri/Psyri/Psurrhē … that was somehow off my radar last time I was there. The entrance to the neighbourhood looks really unpromising, a dark dingy alley that seems like it leads nowhere or at least nowhere safe, but two blocks in and you’re suddenly in a lively area filled with music and sidewalk cafes.”

Well, Psirri has now expanded down that formerly dark and dingy alley, so it no longer looks unpromising. I both sorrow and rejoice.

Why sorrow? Because the magical Secret Entrance is now obvious. It’s as though Narnia were always clearly visible through the wardrobe door.

Why rejoice? Because my love of free and open information is greater than my love of secret entrances. Besides: more Psirri!

FYI, the alley in question is Protogenous Street, leading from Athinas St. into Psirri. The neighbourhood on the other side of Athinas St. is also worth a look.

The next day, another conference trip:

Today, the final conference trip, to Corinth and Sounion. I’ve been to Sounion before, but not Corinth (except for seeing the Acrocorinth from the distance on the way to Mycenae on Wednesday).

People tend to forget Corinth, but it was a major power in its day, in the same league (though not the same League) as Athens and Sparta.

Yesterday was a Delphi trip, but I did that one in 2013, so I decided in favour of more time in Athens instead.

Our tour guide just said, “I’m not an expert. Well, I am, but I’m not saying I am.”

Must be from Crete.

The tour guide seems to think we’re primarily interested in St. Paul, whoever he was. Minneapolis’s brother, I’m guessing. …

More ancient throwbacks: the place where you stop to show your ticket is an elegkhos (usually transliterated “elenchus”), examination. …

I’d forgotten how beautiful the drive to Sounion is.

Sounion itself reminds me a bit of Cabrillo Point in San Diego. …

The Corinth/Sounion tour was actually two tours back to back. According to the schedule, there was supposed to be lunch break in between; but owing to some lamentable misprision we were hustled from the Corinth bus to the Sounion bus with no lunch break. …

I forgot to mention that on one of the tours – Corinth, maybe? – I saw a couple of tour buses with a sign in the front window saying “Victor Davis Hanson.” And I see from the internet that classical scholar Hanson – author of a book comparing Trump to a Homeric hero, another book calling for the u.s. to wage war “hard, long, without guilt, apology or respite” in the Middle East, and an article about the need to warn white children to beware of blacks – does indeed conduct week-long guided tours of Greece with explanatory lectures, for prices ranging between $7200 and $12,500 per person. So Hanson’s group and mine must have been roaming the ruins at the same time. Such a close brush I had with greatness.

After the conference, a brief stay in Hydra:

I first discovered Leonard Cohen’s music in the mid-1990s, and soon hunted down a documentary about him in the local video store. The clip I’ve linked to here is from that documentary. Cohen soon became one of my favourite singer-songwriters (and maybe my just plain favourite). The Cohen connection certainly wasn’t necessary for me to fall in love with Hydra, but it didn’t hurt.

It’s funny how much I like Cohen when the sensibility of his songs is often so alien to me. But the ear wants what the ear wants.

Actual headline from a Leonard Cohen obituary three years ago: “Genius songwriter of music from Watchmen sex scene dead at 82.” …

The conference is over, but I have one more trip, this time to Hydra. I’ve been twice before, but each time for just a frustrating 90 minutes (as part of a 1-day, 3-island tour of the Saronic Gulf). This time I’ll be there for two nights. While, unlike Leonard Cohen (see the video in my previous post), I have no desire to spend ten years there (I’d go batty), 2 nights still seems frustratingly short; but it beats two 90-minute bites.

Farewell to Athens (though I’ll pass through again to get to the airport). I was in the Fivos again. Minuscule rooms and no elevator – but for $60 a night, a central location a few steps from the metro, and a view of the Acropolis as soon as I step out the door, it’s hard to complain. Plus the Fivos staff have been very friendly and helpful.

I’m in a cafe in the Piraeus, having breakfast while I wait to check in for my ferry. The wifi password at this cafe is one of those long strings of numbers I haven’t seen in over a decade.

This cafe can’t decide whether its name is Porto Grill or Porto Chill. I suspect that the former is the real name and the latter a self-assigned nickname. But the signage (sorry, Gary) for the latter is more prominent than for the former.

Well, the bill says “Porto Mediterranean Food,” so who knows?

Looking at the storefront as I depart, I think Chill and Grill are the cafe and restaurant sides of the same establishment. …

Unhappily, just spent 45 minutes in the wrong line. Happily, I arrived well early in anticipation of possible screwups, whether theirs or mine. (Not sure which category my 45-minute diversion falls into, tbh.) Anyway, I’ve now got my tickets and I’m on the boat. Taking the fast route (hydrofoil) thus time rather the slow and scenic, so I should be in Hydra in a bit over an hour.

The island is called Hydra (originally hydrea, “watered”) because it had a source of fresh water. (It no longer has; all drinking water is imported from the mainland.) It’s no connection to Heracles’ multiheaded monster, which was called Hydra because it lived in a lake.

Nowadays it’s pronounced EETH-ra. Sometimes spelled Ydra, Idhra, etc. …

I’m on Hydra, in the Mistral Hotel [or Hotel Mistral; both names are used] – a level walk from the harbour, unlike some hotels here that involve many steps and bring a donkey to carry your luggage. (No cars on Hydra.) This hotel is much more expensive than the Fivos (that’s why I’m only staying two nights) but of course also much nicer.

It’s also right off the courtyard of the restaurant Douskos Xeri Elia, where Leonard Cohen (a singer I may have mentioned once or twice) used to hang out, which I didn’t know when I booked it but it’s a welcome bonus.

It’s a bit cloudy here right now, but it’s supposed to be sunny all day tomorrow.

After this trip I’m going to need new shoes. I seem to have treated these in a shockingly abusive manner.

At the moment I’m sitting on a stone bench gazing at the sea while cats climb around me. It’s very de-stressing (the opposite of distressing).

One of the cats has claimed me and driven the other cat off.

The cat had staked out a space on the bench behind my head. A dog just came along, jumped up on the bench, and tried to hassle the cat. A burst of angry hissing and sharp claws sent the dog running. The cat then quietly reclaimed its place. Now the cat has its paws on my shoulders, rubbing my head, purring, and starting to fall asleep. Well, I can’t leave now.

Now the cat has managed to perch precariously on my chest. I may be here for a while. …

The other cat came back to get in on the petting action, but the first cat was not inclined to share. I did indeed end up spending a while there. Well, there are worse ways of spending an evening than watching a Mediterranean sunset while petting a purring cat. Probably a flea-infested cat, but ya gotta go with the moment. …

I came to Hydra, met a cat, and stayed on a stone bench for an hour and a half.

Yeah, that’s the way it was in those days. …

Now I’m in Xeri Elia, the restaurant where Cohen used to hang out. (I’m such a fanboy.) You can see [on my facebook page] musicians playing, and the two large trees (there are photos on the interwebs of Cohen and friends under one of the trees). …

Xeri Elia closed at midnight and I made my way back to my hotel like a drunk in a midnight choir only not drunk and not singing and not with a group.

The next day:

Free breakfast in the Hotel Mistral: it’s not a buffet, you sit down and they just bring you all this stuff.

This morning I hiked up to Leonard Cohen’s house; it’s undergoing renovations and has a new owner. There’s supposed to be a plaque and a new street sign, but these are missing (perhaps stolen by fans as souvenirs; perhaps stolen by the new owners to make it harder to find). My GPS is rather vague, but I came across a group of Canadian Cohen fans, and each of us had some info the other lacked, and together we found it!

A guide to fellow Cohen house-seekers (oikozetetics?): the house and street aren’t on GPS, but Kriezi Street (“had to go Kriezi to love you ….”) is. Along Kriezi St. is a grocery store with mustard-coloured walls …; the short street leading to Cohen’s house is directly opposite the store.

Cohen’s door has a door knocker in the shape of a hand, with a Star of David behind it. (Unless the new owner changes it.) …

My afternoon walk ….

There are two seaside paths from the main port, one eastward (less pretty) and one westward (prettier). I’ve been down both of them a little bit on previous visits, but not very far (since each visit was just 90 minutes), so I wanted to explore both a bit farther on this trip.

I did the less pretty eastward one yesterday afternoon, saving the prettier westward one for today. …

The Society for Dedicating This Bench to Leonard Cohen dedicated this bench to Leonard Cohen. Yay. On the down side, it looks uncomfortable and there’s no shade. But maybe that’s appropriate, at least for some of his songs.

Sorry, Leonard Cohen Bench Built By Leonard Cohen Bench Builders, but I like this bench better ….

[see my facebook page for the photos]

That’s the Peloponnese across the water. Don’t know if it’s visible in the photo, but the hills are covered with those modern Martian-invasion windmills (as opposed to ye olde picturesque non-functioning windmills on this side).

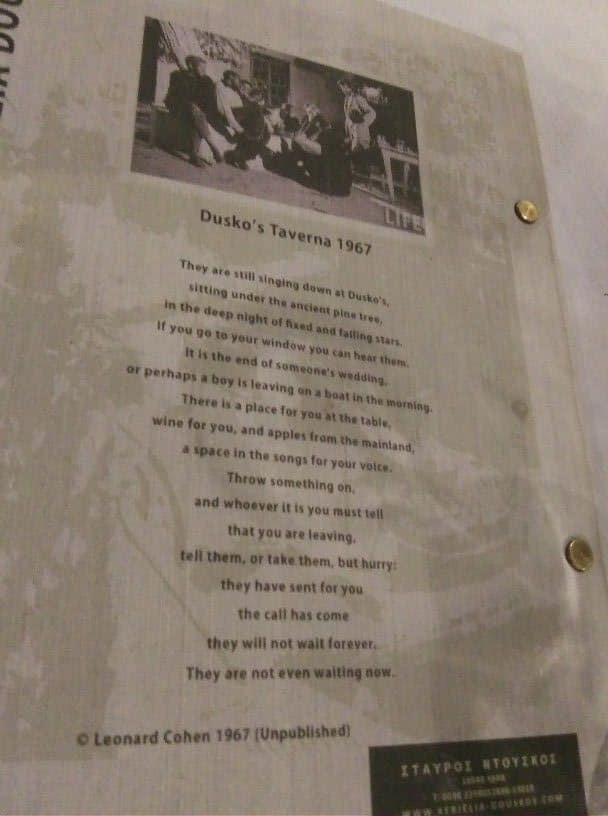

Dinner at Xeri Elia / Douskos again. Note the Cohen poem (and pragmatic self-contradiction) on the back of the menu:

A person at the next table just told the exact same story twice in a row with somewhat different wording, and no one seemed surprised by this. Someone at the table next to me just told a story, and afterward then repeated the story in slightly different words; apparently no one else at the table found it puzzling.

The saffron broth on the mussels was excellent.

Their lemon cake is not as good as their orange cake. …

Hello, Hydra-foil.

Farewell, Hydra!

Two nights is definitely not enough time in Hydra. See my poem.

Back in Athens (the Attalos Hotel this time) for one last night.

Random observations:

a) Why do European hotels generally have no washcloths? Europe has washcloths; I’ve seen them in stores there. But in a hotel, when you shower you either have to use soap alone, or else you have to use a large handtowel that becomes quite heavy and unwieldy once it gets soaked.

b) The metro trains in Athens (at least on some of the lines) make retro-futuristic electronic whooshing/zooming sound effects when they arrive or depart. They sound a bit like the sounds that spaceships or rayguns in a low-budget 1970s sci-fi show might make (not talking Star Wars or Alien here). Or even just part of a disco track from the same period. …

On my 2008 trip to Athens I mentioned:

“Some years back Athens solved its stray dog problem by declaring all the stray dogs to be city property. The city gives them all collars and tags, and takes responsibility for vaccinating them, and feeding any who need it. The result is that Athenian dogs behave differently from dogs I’ve seen anywhere else; their behaviour is neither “domesticated,” nor “stray,” nor “wild.” They move about the city, not in packs, but singly or in pairs; or they sleep on the sidewalk, unperturbed at people walking past or over them. They show no fear or hostility toward humans (apart from one incident I witnessed when a dog suddenly took a dislike to one of the passers-by and chased him down the street), but they also don’t fawn on them for food or affection. (Very different from the ingratiating packs of stray dogs I met in Italy.) They may join a group of human pedestrians for a while, but if so they do it with an aloof air of pretended indifference that seems more feline than canine. They stroll with assured self-confidence, like independent citizens, and are more competent at crossing busy streets than any dogs I’ve ever seen.”

On this last trip, by contrast, I noticed almost no stray dogs in Athens. An internet search reveals the reason:

In 2003 Athens “launched a plan … to sterilize more than 10,000 stray dogs ahead of the [2004 Olympic] Games … ‘The sight of thousands of stray animals living without care in the city streets constitutes an insult to us as civilized people,’ [said] Athens Mayor Dora Bakoyann ….

I guess you could call this the 15 year plan for ridding the city of stray dogs. Fifteen years because that is the average life of a dog. The idea is that if you neuter all the dogs and then set them free again, they won’t be able to have puppies and in 15 years they should all be gone ….”

And so a fascinating and inspiring experiment in the triumph of nurture over nature was ended.

As was, all too soon, my trip:

I’m in Philadelphia, awaiting my connection to @lanta.

I got selected for additional screening in the Birthplace of Democracy this morning, and then a full-body patdown in the Birthplace of the American Republic just now. I can feel the freedom! (Or is that a hand?)