The director of Black Panther explaining the details of a fight scene:

Archive | February, 2018

Something Amiss

I’ve been reading several volumes in Flame Tree Publishing’s Gothic Fantasy series; each anthology collects a number of classic public-domain stories of mystery, horror, science fiction, etc., along with newer stories written especially for the series. The series is a lot of fun, though not without faults (the stories contain a number of misprints, and the newer stories are filled with grammatical errors).

But one feature particularly puzzled me. In the volumes I’ve read so far, the title “Miss” invariably appears with a period after it; for example, “I suppose you mean that you go about all day long with Miss Sybil Merton” becomes “I suppose you mean that you go about all day long with Miss. Sybil Merton.” (And comparison with the original stories confirms that the publisher is adding a period where there was none before.)

I think I’ve figured it out, though.

In contemporary British usage, abbreviated titles that end with the same letter as the unabbreviated title do not use a period (or, in British usage, a “full stop”), while in American usage they do. Thus where Americans would write “Mrs. Jones met Dr. Smith,” their British counterparts would write “Mrs Jones met Dr Smith.”

Yet although Flame Tree Publishing is a British press, these anthologies follow American usage with abbreviated titles. I suspect that’s because they’re marketed more for the American than for the British market (my local Books-a-Million carries large stacks of them).

So my guess is that the publisher, noting that Americans put a period after all abbreviated titles, and forgetting that “Miss” is not an abbreviation, must have assumed that those crazy Americans put a period after “Miss” as well, and duly did so throughout in order to conform to the supposed American usage.

Disco Tech

Legends of Tomorrow has a 70s-themed episode coming up, so four of the stars decided to make a 70s-themed music video. And it does make me a bit nostalgic for the 70s.

Caity Lotz and (especially) Maisie Richardson-Sellers are really good in it.

Brandon Routh and Nick Zano are, um, also in it.

Lotz (who directed it) hasn’t quite mastered how aspect ratios work, though.

True Grit

I recently came across the following striking passage in William Hope Hodgson’s 1912* story “The Thing Invisible”:

I was fighting with all my strength to get back my courage. I could not take my arms down from over my face, but I knew that I was getting hold of the gritty part of me again. And suddenly I made a mighty effort and lowered my arms. I held my face up in the darkness. And, I tell you, I respect myself for the act, because I thought truly at that moment that I was going to die. But I think, just then, by the slow revulsion of feeling which had assisted my effort, I was less sick, in that instant, at the thought of having to die, than at the knowledge of the utter weak cowardice that had so unexpectedly shaken me all to bits, for a time. …

Do I make myself clear? You understand, I feel sure, that the sense of respect, which I spoke of, is not really unhealthy egotism; because, you see, I am not blind to the state of mind which helped me. I mean that if I had uncovered my face by a sheer effort of will, unhelped by any revulsion of feeling, I should have done a thing much more worthy of mention. But, even as it was, there were elements in the act, worthy of respect.

What’s noteworthy about this passage is how closely it follows (whether intentionally or by coincidence, I can’t say) the ethical doctrine of Immanuel Kant. On Kant’s view, a moral action is worthy of respect only if it is motivated by a good will – a respect for the moral law for the moral law’s own sake. If it is motivated instead by some sort of inclination or sentiment (such as charitable acts being motivated by feelings of sympathy), the action is no longer worthy of respect, because if one’s actions depend on favourable sentiments – sentiments whose presence or absence is not under the control of the agent’s will – then that implies that if those favourable sentiments had happened to be absent, the agent would not have performed the action, and so the agent’s having done the right thing is fortuitous and not the expression of a reliable commitment to duty.

Hodgson’s narrator is making a similar point here, holding that since his act of courage was largely motivated by a feeling of revulsion at his own cowardice, it is less worthy of respect than it would have been if motivated by “a sheer effort of will.”

The narrator does not follow Kant entirely, however, since he suggests that his action is still worthy of some respect. For Kant (as I understand him), if an action is motivated partly by duty and partly by inclination, the crucial question is whether the dutiful part of the motivation would still have been sufficient to produce the action, had the inclination been absent. If the answer is yes, then the action is wholly worthy; if no, then the action is wholly unworthy. There is no room in Kant’s account for Hodgson’s notion that an action of mixed motivation might have an intermediate degree of worthiness.

This possibility of intermediate worthiness aligns Hodgson’s conception more closely to Aristotle’s view than to Kant’s, though the alignment is not perfect. For Aristotle, a continent person is one who has to overcome strong temptations in order to do the right thing, whereas a temperate person is able to do the right thing with little or no contrary temptation – though (and this aspect of Aristotle’s theory is often missed) the temperate person is such that he would still do the right thing if strong temptations were present (so the objection that temperate people don’t really deserve credit because right actions are too easy for them doesn’t apply). In Kantian terms, then, both the temperate and the continent person act from duty and not merely inclination, though in one case the inclinations favour the action and in the other case they oppose it.

Kant would regard the temperate and continent persons (and actions) as having equal merit; but Aristotle regards the temperate person (and action) as superior to its continent counterpart, since for Aristotle a virtuous action is supposed to express a healthy and harmonious character, not one (ordinarily) riven by conflict. However, the continent person and action do have some merit. So Aristotle, unlike Kant, allows for intermediate merit here.

But this doesn’t quite apply to Hodgson’s example. In Hodgson’s case it’s not that will is sufficient though inclination is lacking; it’s that inclination is sufficient though will might not have been. Since Aristotle in effect treats will-plus-inclination (temperance) as having more value than will alone (continence), that might mean that he grants some positive moral value to inclination alone (which is more or less what he calls “natural virtue”). But I can’t recall his saying so explicitly.

* Strictly speaking, although the story was first published in 1912, the quoted passage occurs in this form only in the revised 1948 version, the corresponding passage in the 1912 version being much less interesting. But since Hodgson died in the First World War, the revision was presumably made closer to 1912 than to 1948.

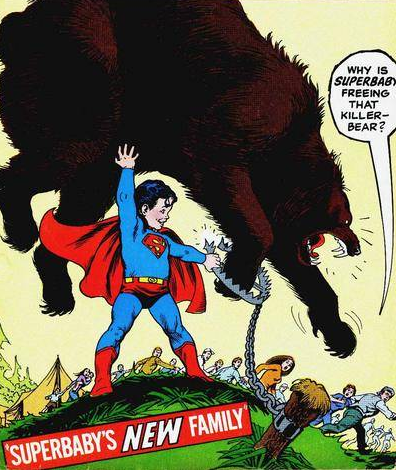

Behold, I Teach You the Superbaby

A delightful video of a toddler watching Man of Steel:

Careful, folks. The transformation of human baby into Kryptonian starts out adorably, sure, but this is how it ends:

How to Get Past a Paywall

You click on an interesting-sounding news story, only to get the message “Sorry, you’ve exceeded your number of free articles.”

Bypassing this message by searching for the story via a Google search used to work, but largely doesn’t any more. There are other methods that reportedly still work, like private browsing or deleting cookies, but there’s one quicker method that usually works for me.

As the story is loading, stop it by clicking the “stop loading” button in your browser. (Search “stop loading page” plus the name of your browser to find out where that button is located. But warning: I’ve only tried this in Firefox.) You want to stop it after it’s fully loaded but before the paywall message pops up; this may take a few tries at first.

Once the story stops loading, don’t scroll down with the scroller on your mouse; that will usually trigger the paywall message anyway. Don’t even let your cursor linger over the page. Instead, move your cursor over to the right-hand scroll bar, click-hold on it, and then scroll down manually with your mouse to read the article.

Let me know if this works for you!