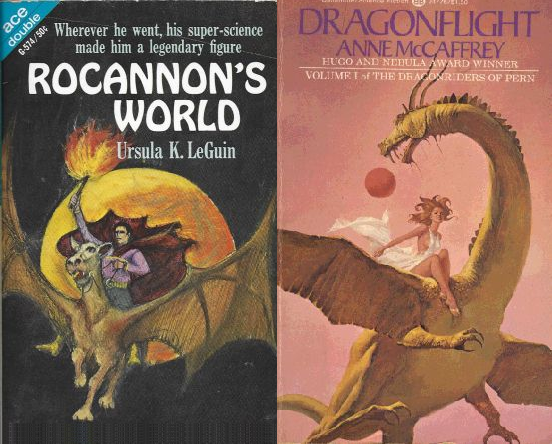

In 1966, Ursula Le Guin published Rocannon’s World, the first novel in her Hainish series.

Two years later, in 1968, Anne McCaffrey published Dragonflight, the first novel in her Pern series.

There are striking parallels between the two novels. Both feature a world with the trappings of fantasy (including flying steeds, and mediæval technology and social structures), yet grounded in a science-fiction framework of future planetary colonisation. Both also feature a telepathic protagonist who fulfills a prophecy; both involve voyages in which time passes in a nonstandard manner; and both begin in a chilly castle on a high hilltop, with a discontented heroine scheming to reclaim her stolen legacy.

So far all that could be coincidence, though. Certainly the specific story details are quite different. And after all, giving a fantasy story a science-fiction twist and technological grounding by transplanting it to the future and/or to another planet is an idea older than either book (see, e.g., the various works in the “planetary romance” genre, from Edgar Rice Burroughs to Marion Zimmer Bradley).

What I’m inclined to think is not a coincidence is the similarity between the two novels’ opening passages. Both begin with a meditation on the relation between myths or legends on the one hand and historical facts on the other, and both do so in conjunction with identifying the real-world star around which the story’s fictional planet revolves. Here’s the opening of Rocannon’s World:

How can you tell the legend from the fact on these worlds that lie so many years away? – planets without names, called by their people simply The World, planets without history, where the past is the matter of myth, and a returning explorer finds his own doings of a few years back have become the gestures of a god. Unreason darkens that gap of time bridged by our lightspeed ships, and in the darkness, uncertainty and disproportion grow like weeds.

In trying to tell the story of a man, an ordinary League scientist, who went to such a nameless half-known world not many years ago, one feels like an archaeologist amid millennial ruins, now struggling through choked tangles of leaf, flower, branch and vine to the sudden bright geometry of a wheel or a polished cornerstone, and now entering some commonplace, sunlit doorway to find inside it the darkness, the impossible flicker of a flame, the glitter of a jewel, the half-glimpsed movement of a woman’s arm.

How can you tell fact from legend, truth from truth?

Through Rocannon’s story, the jewel, the blue glitter seen briefly, returns. With it, let us begin, here:

Galactic Area 8, No. 62: FOMALHAUT II.

High-Intelligence Life Forms: Species Contacted ….

And here is the opening of Dragonflight:

When is a legend, legend? Why is a myth, a myth? How old and disused must a fact be for it to be relegated to the category “Fairy-tale”? And why do certain facts remain incontrovertible, while others lose their validity to assume a shabby, unstable character?

Rukbat, in the Sagittarian sector, was a golden G-type star. It had five planets, plus one stray it had attracted and held in recent millennia. Its third planet was enveloped by air man could breathe, boasted water he could drink, and possessed a gravity which permitted man to walk confidently erect. Men discovered it, and promptly colonized it, as they did every habitable planet they came to and then – whether callously or through collapse of empire, the colonists never discovered, and eventually forgot to ask – left the colonies to fend for themselves. …

Once relieved of imminent danger, Pern settled into a more comfortable way of life. The descendants of heroes fell into disfavor, as the legends fell into disrepute.

This, then, is a tale of legends disbelieved and their restoration. Yet how goes a legend? Where is myth?

So yeah, I’m very strongly inclined to think that McCaffrey was influenced by Le Guin here. (Though McCaffrey wisely didn’t attempt to imitate the “millennial ruins” passage. I’m very fond of the Pern series, but when it comes to sheer beauty of language, McCaffrey is just not in Le Guin’s league – and Rocannon’s World isn’t even one of Le Guin’s best novels.)